What are the Chances to Revive Democracy in Russia?

Russia is one of the few countries in the world where historically the results of an election are known before the voting takes place. It looks like the parliamentary elections due to be held later this month are no exception.

But these elections are taking place against a backdrop of voter dissatisfaction fueled by a failing economy, growing inflation, environmental problems, and a health crisis largely made worse by the coronavirus.

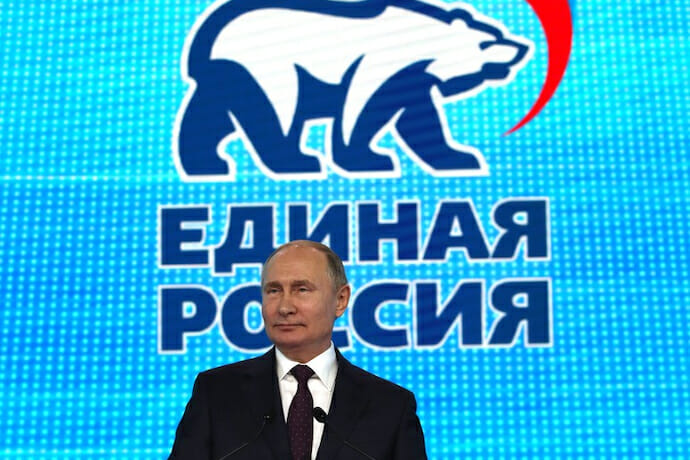

United Russia, the ruling party that has supported Vladimir Putin throughout his presidency, is expected to retain a majority of its seats in the next Duma.

But the government appears to be taking no chances in trying to cling on to its rapidly evaporating power base. Leading opposition figures remain in jail and other independent politicians have not been allowed to participate in the elections on dubious grounds. Alexei Navalny, the opposition leader, has been in jail since January on old fraud charges seen as politically motivated. His nationwide political organisation, which has alleged corruption linked to both Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, the former prime minister, has been liquidated as extremist. Many of its members have fled to avoid arrest.

Ever-changing election rules (now also allowing Russian passport-holders in eastern Ukraine to vote in Duma elections while encouraging online voting) could make the process more vulnerable to fraud.

According to The Guardian, “Putin remains far more popular than United Russia and has declined to join the party, probably to avoid dragging down his ratings. However, he appeared at the party’s conference last week and promised the equivalent of £150 payouts to members of the military and £100 to pensioners before the elections, while calling for similar proposals for families with children. While the offers are not directly linked to voting, they are seen as an easy, if expensive, way to drum up support.”

Fyodor Krasheninnikov writes in Deutsche Welle, “The thinly-veiled bribery of voters, all sorts of manipulations, mobilising administrative [resources] and persecution of the critics of the regime – these are the election tactics of Putin and his party in 2021.” Krasheninnikov is an opposition political commentator who recently left for Europe because he said he felt pressure from the government. “All that Vladimir Putin can offer voters is fear, coercion, and a little money.”

Two other parties have generally run in second and third place; these are the CPRF (Communist Party of the Russian Federation) and the so-called LDPR (Liberal Democratic Party of Russia), which is in fact a right-wing party with harsh nationalist rhetoric. These are in effect satellite parties of United Russia, lacking credibility and offering no real choice for voters in view of their status as surrogates of United Russia.

It appears that non-orthodox voters with democratic convictions have few options if they wish to oppose the ruling party.

But so many Russians have been deprived of the right to be elected prior to the elections, that there is a huge swell of discontent which could make a “shoe-in” for United Russia difficult.

Within the opposition, there is widespread discussion about the right way to present some alternative ideas by electoral methods (shunning elections or making protest votes) through the mobilisation tool “smart voting” created by Alexei Navalny.

Given the difficulties registering new parties and becoming a candidate for office, the only political party reminiscent of the years of freedom in the 1990s seems to be the social-liberal party Yabloko (the Russian word for apple). This is a full member of the European Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) party, which has recently been rechristened, Renew Europe.

Importantly, few leading candidates from the party were prevented from participation in the elections, and others were labeled as “foreign agents.”

Tactical voting looks like a trap that may not achieve anything other than splitting the vote and delivering victory to United Russia on a plate. In essence, the choice for the democratic opposition would appear to be either to boycott the vote, or to support Yabloko.

While Navalny’s movement and Yabloko are disunited on many issues, they agree on one thing: their existence is important for freedom, pluralism, and democracy in what they see in “an artificial political diversity under a virtual one-party system.”

These elections may be the last chance for these two opposition parties to bring about real change and to turn the tables before it is too late.