What Comes After Iran-Turkey’s Anti-Kurd Détente?

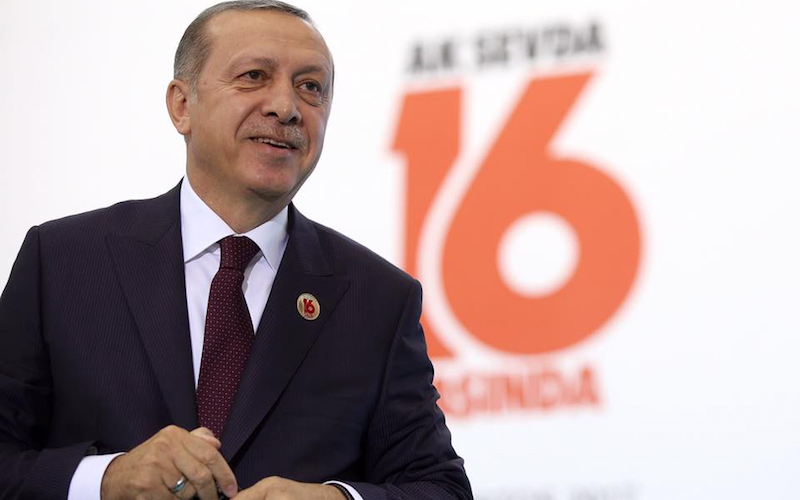

The recent visit to Turkey by the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Iran, Brigadier General Mohammad Hossein Bagheri has opened up a new chapter in Turkey-Iran relations. It was the first such visit since Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution and included meetings with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and other top-ranking Turkish officials.

Although the details of the meetings were kept secret at the time, the presence of the Head of the Ground Force of the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC), Brigadier General Mohammad Pakpour in the talks was particularly important because of his long-time involvement in the IRGC’s operations against the Kurdish autonomy movements during and after the Islamic Revolution. That aside, the geopolitical and regional security context in which the talks took place also merit pondering.

While the Islamic State (IS) is falling, the key regional powers, i.e. Russia, Turkey, and Iran are fretting over the potential break-up of Syria, and the prospects of Kurdish statehood in northern Iraq. There is also a considerable power vacuum to be filled by the competing geopolitical actors as a result of the shrinking of IS-held territories in Iraq and Syria.

The timing of Iran-Turkey talks was all the more significant mainly due to the confusion surrounding the Iraqi Kurdistan independence referendum scheduled for 25 September. Therefore, despite the myriads of divergent positions Iran and Turkey have adopted toward the Syria conflict since 2011, the two rival states appear to have reached a consensus around the single issue or, say, the most immediate threat that binds their security interests together— that is fighting the Kurdish separatists.

It can be argued that the principal objective of the new strategic opening in Turkey-Iran ties is three-fold.

First, the opening is aimed at preventing Kurdish mobilization in three main discrete locations:

In and around the Qandil Mountains on the Iran-Iraq border where the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) is based. A high-ranking Turkish official has reportedly said that “some 800-1,000 PKK terrorists” are in and around the city of Maku (northwestern Iran) where the PKK and its Iranian affiliate, PJAK enter Turkey and launch guerrilla attacks. Hence, the construction of the 144-kilometer wall on Iran-Turkey border is intended to deter PKK and its offshoots from staging such attacks.

In the city of Afrin in the northern Syrian province of Aleppo, which is currently controlled by the PKK’s Syrian branch, the People’s Protection Units (YPG). Ankara fears that the three self-administered cantons of Afrin, Kobane and Cizre may unite and ultimately create an independent Kurdish state near Turkish borders unless the PKK-affiliated militias are defeated within and possibly outside the Jarablus/al-Bab/Azaz triangle. According to Daily Sabah, a group of Turkish intelligence and military officers held secret talks in Tehran in mid-July together with representatives from Iran and Russia in which they discussed the future status of Afrin.

In Northern Iraq which is ruled by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and is seeking independence from Iraq. During the Ankara talks Iranian and Turkish officials reiterated their firm stance against KRG’s decision to hold a referendum next month, insisting that this would be a recipe for another conflict in the region. Ankara and Tehran worry that such a move would embolden the Kurdish populations inside Iran and Turkey to opt for independence.

Second, both Iran and Turkey have tacitly agreed to thwart US attempts at exploiting the security vacuum created in the war-torn territories as a result of the steady decline of IS in Iraq and Syria. Unlike Obama, Trump’s administration appears to have shown no scruples about expanding the US influence in the Middle East, both in strategic and political terms. However, Turkey views the US partnership with the PKK-linked YPG militias as an “existential threat” to its territorial integrity. Erdoğan has warned that Turkey will do whatever it takes to stymie efforts at setting up of a [Kurdish] state in northern Syria.

Finally, the temporary anti-Kurd convergence is used by Iran and Turkey as a “successful” precedent to broaden it to work toward annihilating IS. This contingency would happen even if Ankara were to reluctantly tolerate Bashar Assad as the leader of Syria and give concessions to Damascus and Tehran at the expense of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and other rebel forces as evidenced by what is transpiring in Syria’s northwestern Idlib province.

The perceived threat of Kurdish statehood in northern Syria and the looming question of Iraqi Kurdistan independence has convinced Iran and Turkey at least for now to forgo their ideological differences for the sake of eliminating the immediate threat of Kurdish mobilization/statehood in the region. In fact, forming ad hoc and expedient alliances that could serve mutual interests is seen as a permanent fixture of Iran-Turkey relations throughout history. The only question is which threat is the most immediate one for them to join forces in the hope of defusing it.

Whether or not the recent alliance will pay off is an open question. What seems to be a veritable assumption, however, is that Turkey and Iran have exploited the recent rift in the Gulf Cooperation Council, the decline of IS, and rising Kurdish mobilization along their borders to their own benefit while at the same time striving to realign their positions on the basis of realpolitik considerations, namely balancing the US influence in the region. Hence, the new chapter in Turkey-Iran relations will also entail huge implications in terms of the future of US policies toward the Syrian conflict and Iraq. Only time will tell as to whether or not the recent Turkish-Iranian anti-Kurd détente will last against all odds.