Why the Global South Will Always Second Guess the West

In an era marked by the intertwining of global interests and the constant exchange of cultural values, the vestiges of a postcolonial mindset within certain Western corridors of power stand as an anachronism. This outlook, which mistakenly regards societies outside of the West as “less civilized,” breeds an unwarranted sense of moral supremacy. It is this self-appointed moral authority that often results in condescending rhetoric, with Western entities at times presuming the right to dictate the internal matters of other nations. Far from fostering harmony, this patronizing stance exacerbates regional instabilities and strains international relations, thereby posing a significant obstacle to the collective pursuit of global peace.

The ‘Golden Arches’ theory, a colloquial term for democratic peace theory, posits that liberal democracies are less likely to engage in armed conflict with one another. This premise underscores a prevalent narrative among Western powers that championing democratic governance and liberal norms may serve as a universal salve for conflict. Proponents of this theory argue that a proliferation of democratic states could herald an era of reduced global hostilities. However, the imposition of democratic ideals — at times extending to military intervention — challenges the principle of sovereign self-determination. It raises critical questions about the respect for national autonomy and the richness of global diversity. Such ideological exports, when coercive, not only contradict the core tenets of self-governance but also risk undermining the very tapestry of international plurality that they seek to preserve.

Abandoning the postcolonial mindset is imperative for cultivating a more peaceful, dynamic, and interdependent world. Moreover, it is crucial for fostering genuine trust between the West and the Global South, which have often been subjected to colonization by Western powers. Genuine trust serves as the cornerstone for fostering productive cooperation and establishing global peace and stability. The West must engage in less lecturing and more listening. The Global South seeks more cooperation and less dictation from their Western counterparts.

The rhetoric of “our garden” versus “their jungle” emblematically underscores a lingering postcolonial Western worldview when juxtaposing its society against others globally. This metaphorical framework not only harks back to but also perpetuates the dated narratives of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In those eras, religious exegesis and nascent scientific theories were misappropriated to validate slavery and promulgate beliefs of racial hierarchies, notably positing Africans as intellectually subordinate to Europeans. Such ideologies bolstered colonial justifications, portraying European powers as benign mentors, destined to ‘elevate’ and ‘enlighten’ ostensibly less-developed nations, with African societies frequently being the focal point of these paternalistic endeavors.

At the inaugural event of the European Diplomatic Academy in Bruges, Belgium, in October 2022, EU diplomat Josep Borrell sparked controversy with his remarks. Borrell metaphorically referred to Europe as a “garden”—a symbol of order and prosperity—and contrasted it with the “jungle,” which he used to describe areas outside the EU. He suggested that rather than isolating Europe with insurmountable barriers, engagement with the “jungle” was essential. Emphasizing the imperative of European solidarity over divisions of religious and national identity, he stated, “I’m Catalan, I’m Spanish, I’m European, and there is no contradiction between these three things, by the contrary, they enriched me,” underscoring how multiple identities coexist and enhance his personal experience.

Promoting an inclusive “you and me” approach over an adversarial “me against you” perspective, Borrell faced backlash for potentially insinuating a superior-inferior dynamic between Europe and other regions. In the wake of criticism, he clarified his intentions, stating that the garden-jungle metaphor has long been a fixture in academic and political discourse and that his comments were misinterpreted. Borrell advocated for humility and a deeper understanding of the world, including the Global South, by EU ambassadors. His remarks have reignited discussions on the language and mindset that European diplomacy should adopt in an increasingly interconnected global landscape.

The discourse delineating Europe as a “garden” and the wider world as a “jungle” has found resonance in media commentary across the Atlantic, particularly in the context of Ukraine’s refugee crisis post-Russian invasion. British journalist and member of the House of Lords, Daniel Hannan, writing for The Telegraph, invoked this dichotomy to elicit empathy for Ukrainian refugees by highlighting their European identity and lifestyle — characterized by the familiar trappings of Instagram and Netflix, and the practice of participating in democratic elections.

Hannan’s commentary draws a stark line between the “civilized” European and the “less enlightened” outside it, inferring a difference in levels of sophistication and implying a European moral high ground. This distinction is further emphasized as Hannan applauds Western embassies for their didactic approach to global issues like climate change and LGBT+ rights outside Europe. The insinuation is that Europe’s moral compass and sense of civilization afford it the right to intervene in the affairs of other nations under the guise of benevolence.

However, such narratives risk reinforcing a perceived hierarchy between the West and the Global South, undercutting the ideal of equal partnership. The language of “garden” and “jungle” echoes a sentiment that could potentially alienate rather than foster cooperative global relations. This reflection invites a reevaluation of how the West engages with the rest of the world, moving away from a paradigm of superiority and towards one of mutual respect and collaboration.

As the European Union grapples with its diplomatic identity on the world stage, a series of incidents have cast a spotlight on the complexities of international relations and the narratives perpetuated by some Western diplomats and media commentators.

In a notable instance, South African Minister of International Relations Naledi Pandor, in a meeting with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken in August 2022, leveled criticism at Western nations for what she perceived as a heavy-handed approach to Africa. Such encounters underscore the tensions between the espoused values of inclusivity and the actions perceived as coercive or condescending by African officials.

The controversy deepened when, in June 2023, Romania recalled its ambassador, Dragos Tigau, from Nairobi after comments that were widely viewed as derogatory towards African diplomats emerged, leading to a swift and widespread backlash. The Romanian Foreign Ministry extended an apology in the wake of the incident, an effort to quell the diplomatic turbulence that ensued.

Further straining the discourse, CBS’s senior correspondent Charlie D’Agata, while reporting live from Kyiv, drew controversial comparisons between the Ukrainian capital and cities in Iraq and Afghanistan. NBC correspondent Kelly Cobiella differentiated Ukrainian refugees from Syrian ones based on religion and race. Al Jazeera’s commentary highlighted socioeconomic status as a distinguishing feature, and on France’s BFM TV, journalist Phillipe Corbé emphasized the European identity of Ukrainian refugees.

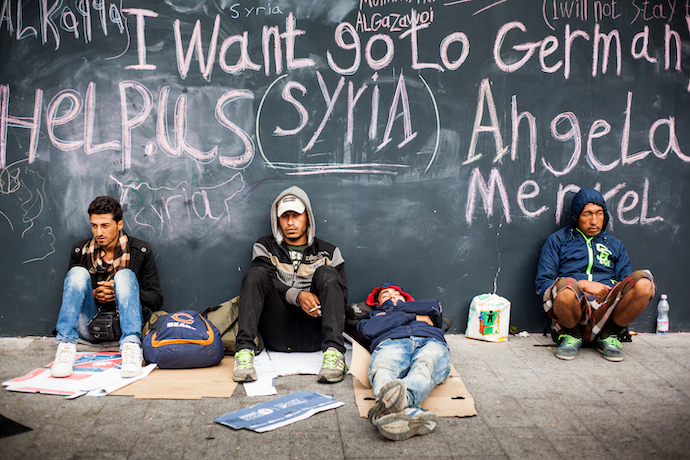

These instances highlight a recurring dichotomy where Ukrainian refugees are characterized as relatable and “European,” in contrast to non-European refugees. Such characterizations, which at times invoked physical characteristics like “blue eyes and blonde hair,” as noted by Ukraine’s Deputy Chief Prosecutor David Sakvarelidze in a BBC interview, reveal an undercurrent of bias that privileges certain refugees over others.

The cumulative effect of these narratives raises critical questions about the consistency of Western values concerning inclusivity and the latent biases that may influence international diplomacy and media coverage. The challenge ahead lies in aligning rhetoric with action, ensuring that the principles of equality and non-discrimination are upheld in practice, not just in policy.

In the landscape of humanitarian crises, the distinction drawn by Western commentators between Ukrainian refugees and those from other regions has stirred a debate on cultural empathy and the deep-rooted biases within European public perception. The depiction of Ukrainian refugees as sharing a religious, ethnic, and lifestyle affinity with Europeans — underscored by the imagery of automobile use and social media activity — seems to be fostering a sense of kinship and a more welcoming response in Europe.

However, this selective portrayal contrasts sharply with the often less favorable depictions of refugees from the Middle East and Africa, who are sometimes characterized as “less cultured” or “less enlightened.” Such differentiation does not merely reflect disparities in cultural identity but suggests an implicit assertion of European superiority.

This narrative is further entrenched by the implicit reliance on the democratic peace theory, which posits that democracies are inherently more peaceful, and hence, their citizens are perceived as more “civilized.” Consequently, this dichotomy of “our civilized garden” versus “their untamed jungle” not only underscores an unequal valuation of human experiences based on geography and culture but also calls into question the universality of Western liberal values.

The crux of the issue lies in a need for Western elites and societies to bridge the gap between professed egalitarian ideals and the realities of cultural prejudice. Acknowledging and addressing these disparities is essential to fostering a genuinely inclusive approach to global humanitarian efforts.

In the intricate narrative of Middle East politics, Thomas Friedman, writing for The New York Times, utilized zoological metaphors to elucidate the complex dynamics of the region for his readership. In a column following Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7, Friedman cast the United States as an “old lion,” presiding over the Middle Eastern “jungle,” while Iran was likened to a “parasitoid wasp,” an analogy supported by his citation of Science Daily.

Further extending this metaphor, he described Lebanon, Yemen, Syria, and Iraq as “caterpillars,” hosts to the “eggs” of various groups such as the Houthis, Hezbollah, Hamas, and Kata’ib Hezbollah. Concluding his analysis, Friedman quipped about preferring the raw clarity of Animal Planet over CNN for insights into the Middle Eastern geopolitical landscape.

This zoological framing draws parallels to George Orwell‘s Animal Farm, which allegorically critiqued the Soviet Union, communism, and Stalin’s authoritarian rule. The use of such analogies by Western commentators to depict adversaries as less civilized beings remains a contentious rhetorical device, one that often risks oversimplification and perpetuation of cultural stereotypes. It also reflects a broader pattern where geopolitical conflicts are distilled into simplistic narratives that may not fully encompass the complexities of international relations and human dignity.

The revelation of a 1971 telephone conversation between then-Governor Ronald Reagan and President Richard Nixon surfaced a few years ago, shedding light on the troubling racial attitudes held by the two men. In the exchange, Reagan referred to United Nations African delegates, who were celebrating China’s admission to the UN, as ‘monkeys,’ a deeply offensive and racist term. Nixon’s laughter and his subsequent comment further underscored the disparaging view of Africans as held by both men.

Fast forward to 2018, this issue of derogatory language aimed at African nations reemerged in the political discourse of the United States. Former President Donald Trump, in a discussion with U.S. senators on immigration, reportedly used the term “shithole countries” to describe African nations, questioning why the U.S. did not receive more immigrants from countries like Norway instead.

These episodes, almost half a century apart, highlight a persistent issue in Western political rhetoric: the challenge of shedding long-standing perceptions of superiority and inferiority. Despite the passage of time and advancements in cultural understanding, such sentiments reveal a resistance to change within some quarters of Western political thought and dialogue. This continuity of divisive language not only reflects on the individuals who use it but also raises broader questions about the prevailing narratives within certain segments of society and the work that remains in the journey toward inclusivity and respect in global relations.

The employment of dehumanizing language in the geopolitical discourse by Western powers has a storied and controversial history. This rhetoric often serves as a prelude to punitive measures, including sanctions and military interventions, which have historically led to widespread human suffering, as evidenced by events in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and other nations.

In 2002, President George W. Bush introduced the term “Axis of Evil,” grouping Iraq, Iran, and North Korea as principal threats to global peace. The validity of this categorization has been hotly debated, particularly in light of the discredited assertions regarding Iraq’s possession of weapons of mass destruction and the country’s alleged association with Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda.

Decades later, the legacy of this nomenclature persists in American political rhetoric. In a significant echo of Bush’s terminology, U.S. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell dubbed China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran the “new axis of evil,” despite these countries’ significant global population representation. This rhetoric continues to stir debate over its potential to complicate the pursuit of international diplomacy and multilateral engagement.

The implications of such terminology are profound. Casting entire nations under the shadow of “evil” risks not only alienating over a fifth of the global population but also undermines the nuanced dialogue necessary for peace and stability. These characterizations, while serving to delineate allies and adversaries, may also stifle opportunities for cooperation on global issues where mutual interests align. The challenge for contemporary statesmanship is to balance the need for security with the imperative of constructive engagement in an interconnected world.

In an era where digital platforms reach billions and bridge continents, Western narratives that imply a dichotomy between the “civilized” self and the “less-civilized” other find global audiences. These portrayals are met with growing rejection from nations labeled as such, who refuse to be cast as inferior or malevolent within the global dialogue.

The prevailing paradigm of cultural superiority not only fails to foster global harmony and cohesion but actively fuels discord and division. The international community is shifting towards a multipolar reality where the unilateral and assertive stances of certain global powers threaten to destabilize long-standing peace and cooperation.

As the world confronts complex challenges, from climate change to geopolitical conflicts, a reinvigorated commitment to dialogue is indispensable. The pressing need for an effective and inclusive multilateralism has never been clearer.

The West, with its significant influence, stands at a crossroads. The path forward calls for a paradigm shift from a competitive to a cooperative stance in global affairs. Embracing principles of reciprocity, equality, and mutual respect, the West can play a pivotal role in shaping a world not divided into gardens and jungles but united as a diverse ecosystem with symbiotic relationships across varied habitats and cultures. This approach does not merely offer a moral high ground but is a strategic imperative for a sustainable and peaceful global order.