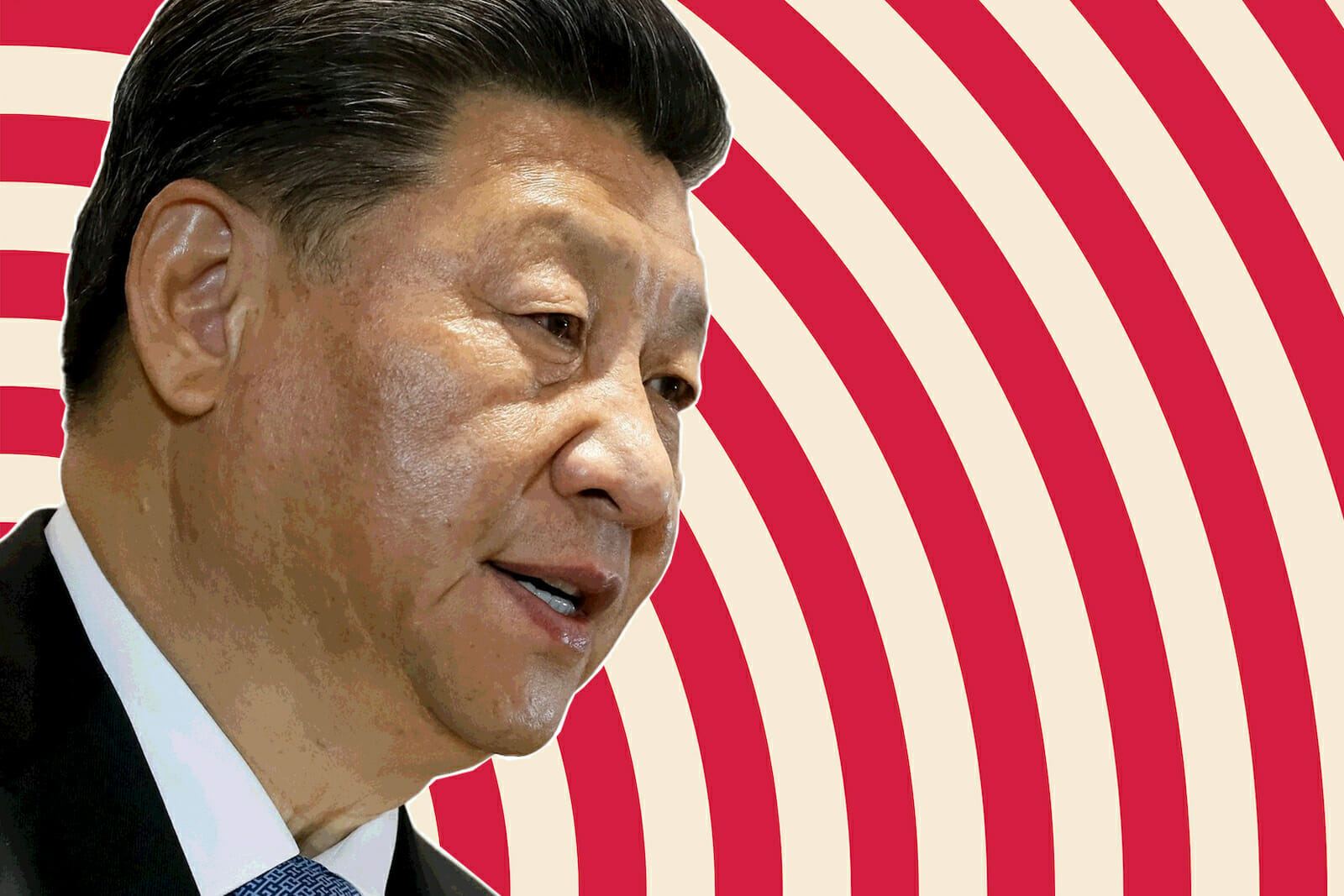

Will China’s Sanctions Bite Americans?

In January, China sanctioned 28 Trump administration officials, including Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, for actions “which have gravely interfered in China’s internal affairs, undermined China’s interests, offended the Chinese people, and seriously disrupted China-U.S. relations.”

The sanctions bar former Trump administration officials and their families from traveling to mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macao. The officials and “companies and institutions associated with them” cannot do business with China.

Donald Trump’s former national security advisor John Bolton, a sanctions target, replied “Great news…I accept this prestigious recognition of my unrelenting efforts to defend American freedom.” Former trade adviser Peter Navarro called the sanctions a “badge of honor from the dictatorship that has killed millions with its [COVID] virus.”

Not everyone in Washington, D.C. was so sanguine.

One observer called China’s sanctions a “serious national security threat” and suggested the business community and the government “respond collectively” to China’s action. Senator Tom Cotton says they are a “dangerous and insidious escalation of China’s effort to influence American policy.”

China telegraphed its intent in May 2020, but the precipitating actions were likely the U.S. determination that China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims was genocide, and sanctions against Chinese officials for crackdowns in Tibet and Hong Kong.

The U.S. may be at the point of diminishing returns for sanctions. They look increasingly farcical in light of sanctions against NATO ally Turkey for buying a Russian missile system (after Turkey and the U.S. couldn’t agree on the sale of a comparable American system) and against European companies building the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline from Russia to Germany (because Germany’s decision to decommission nuclear power plants requires increased imports of natural gas).

U.S. over-reliance on sanctions in lieu of negotiations – or letting friendly countries do what’s in their interest – has led it to penalize policy differences instead of genuine bad behavior.

The U.S. may find sanctions less useful in the future against China. Foreign direct investment is increasing in China as it declines in the U.S. and China’s economy may overtake the U.S. as early as 2026. And China’s “wolf warrior” diplomats will push back hard against what Beijing sees as U.S. interference in its internal affairs.

President Trump’s efforts to decouple the economies of the U.S. and China may have been too late after decades of U.S. accommodation of China’s economic rise, which rested partly on stealing the technology it couldn’t force foreign firms to hand over as a condition of market entry. Though some American firms are shifting production away from China, the country remains the biggest market in the world and a key part of the global supply chain, so the private sector may be reluctant to heed the call for collective action with Washington in the absence of a sound business case.

Critics have long decried America’s over-reliance on sanctions, which in one egregious case wrecked Iraq’s middle class, contributing to the failure of the U.S.-led economic reconstruction and political reconciliation. And Trump’s Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin felt sanctions would erode the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency and hurt the U.S. economy, a concern belittled by then-national security advisor John Bolton. How dare he worry about the economy!

Sanctions were all fun and games until they had the potential to hurt the income of someone inside the Beltway, which is part of the reason for the agita. But will most Americans care? No.

In fact, China’s action may be a blow for good governance. In recent years about ten percent of the Treasury Department’s sanctions staff has departed for the private sector to advise clients on the sanctions they created. That’s nice work if you can get it. But if a sanctioned executive or legislative branch official can’t quit government to monetize the skills and experience he acquired at taxpayer expense he may be more inclined to stay in the public sector. Or work for an organization that doesn’t have a financial relationship with China. We may see less of the “revolving door” and we should thank Xi Jinping for that.

Don’t worry about the lobbyists, consultancies, and law firms; they’ll just have to look harder for China experts. In fact, Chinese sanctions become a measure of effectiveness, like how Sicilians used to judge anti-mafia prosecutors: the good ones were killed.

China’s threats may work and cause some officials, concerned about their future, to pull their punches. It’s hard to promote yourself as a China expert, after all, if you can’t get a visa to China. And Chinese officials can refuse to appear in any venue that also features sanctioned persons, which may cause universities, think tanks, and conference organizers to reconsider who they affiliate with. China will probably be opaque and inconsistent in applying sanctions to keep American institutions apprehensive about offending Beijing and ready to accommodate its real and imagined concerns.

I’d say the U.S. had a good run with economic sanctions, except that they couldn’t even make Cuba change its ways. The U.S. may finally have to confront a target that can effectively strike back, and with personal financial consequences for the individual members of the policy and sanctions bureaucracy.