Will Euro 2020 and the Tokyo Olympics Boost Economic Growth?

During the run-up to last week’s Euro 2020 final, Rishi Sunak, the British finance minister, suggested that an England victory could be a boost for the country. Not only would it generate a feel-good mood, but it could have tangible outcomes in the form of greater consumer spending and an overall improvement in the nation’s finances.

Meanwhile, Tokyo’s postponed Olympics Games will start on July 23. But in contrast to Sunak’s optimistic note, there is a general expectation that Japan will fail to recoup the costs of the Games, owing to the absence of spectators and tourists. The gloomy prognosis comes after a year where there were hopes that the Olympics might help kickstart Japan’s economic recovery, especially after the hit it took because of the pandemic.

Claims about positive outcomes have long been made about sporting events. Sunak’s suggestion is the latest in a long line that includes those about England’s sole World Cup win in 1966 having helped the Labour Party win re-election that same year. But there’s a problem with this: England beat Germany on a hot summer day at the end of July whereas the 1966 election took place several months earlier, in March.

Four years later, Brazil won the World Cup with arguably the best team of all time. Their success coincided with the so-called “economic miracle” that swept the country during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Other than Brazil, however, the only other country to see its economic growth rise more the year after winning the World Cup was Argentina. But the increase of GDP growth by 10% in 1979 contrasted with the shrinking of the national economy by 4.5% the year before. Far more common for World Cup winners was to see similar levels of economic growth in the years before, during, and after.

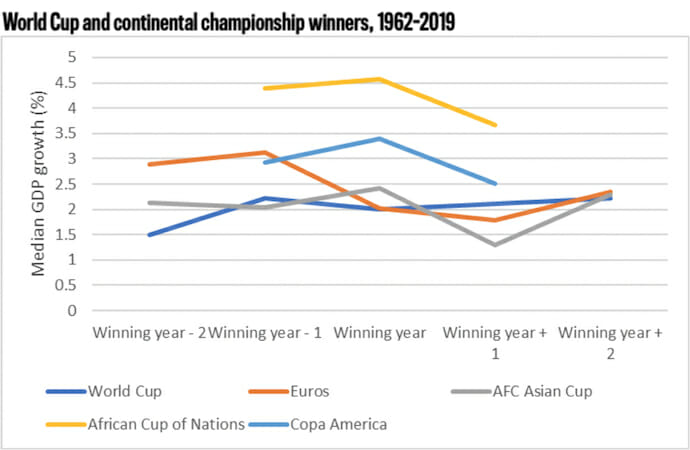

The trend seems to hold when other football championships are brought into the equation (Figure 1). By looking at the economic performance of the winners of the continental championships in Europe, Asia, South America, and Africa, the findings indicate that there is no economic “bounce” after victory. Instead, the level of economic growth slows the year after winning.

In sum, the evidence is contrary to the assertions made. So why do such claims persist? Perhaps one reason is to provide some justification for the investment put into supporting a team. Rather than celebrate its success on its own merits, some narrative or explanation needs to be provided, to justify the effort put in. Indeed, both the then military governments in Brazil in 1970 and Argentina in 1978 were keen to associate themselves with their football team’s success, as a way of cementing their legitimacy among the population.

But it is not just authoritarian regimes that lay claim to their team’s success. France’s win in 1998 was celebrated as a victory for multiculturalism, given the racial diversity of the team. More recently, England’s passage to this Euro final has exposed tensions over racism. While the Conservative government has tried to associate themselves with the team and its success, the players themselves have criticised some ministers for wanting to have it both ways, having backed fans who booed them when they took the knee against racism at the start of the tournament.

If it is not the victors that benefit from greater economic success then, what about the hosts? When Barcelona hosted the Summer Olympics in 1992 it was regarded as a great success. The city was economically and physically rundown in the preceding years. But after winning the right to host the Games in 1986, the city began to rebuild. In addition to the improvements in infrastructure, visitor numbers grew, both in the year of the Games and after. Today, Barcelona is one of the premier tourist destinations in Europe and one of the continent’s most vibrant and dynamic cities.

Similar hopes have been present for subsequent and aspiring hosts. Before London decided to bid for the 2012 Olympics, the government undertook an appraisal to evaluate the costs and benefits of doing so. As part of its bid and during the buildup to 2012, the government stressed the “legacy” that hosting the Games would leave. Not only would they be physical, in the form of new sporting venues, better roads, transport, and housing, but it would also lead to other, more intangible benefits, like a more active and healthy population.

Studies over the past decade have challenged those assumptions. In addition, the cost of hosting the Games has become increasingly expensive. With the exception of Los Angeles in 1984, no city has made a profit. In Montreal’s case, for example, the difference between anticipated and actual costs meant that taxpayers were still paying for the 1976 Games three decades later.

A big reason for the high costs of being a host is the sheer size of these events. The Tokyo Olympics will have more than 330 events and over 11,000 athletes taking part while recent World Cups have had more than 3 million spectators attend matches. The presence of so many people requires investment to either build new or upgrade existing infrastructure.

At the same time, the hosts do not see much of the income generated as a result of the event. While they take on the cost of being hosts, it is the International Olympic Committee and FIFA – the two international sporting organisations that oversee the Olympics and the World Cup – who collect the bulk of the revenue produced.

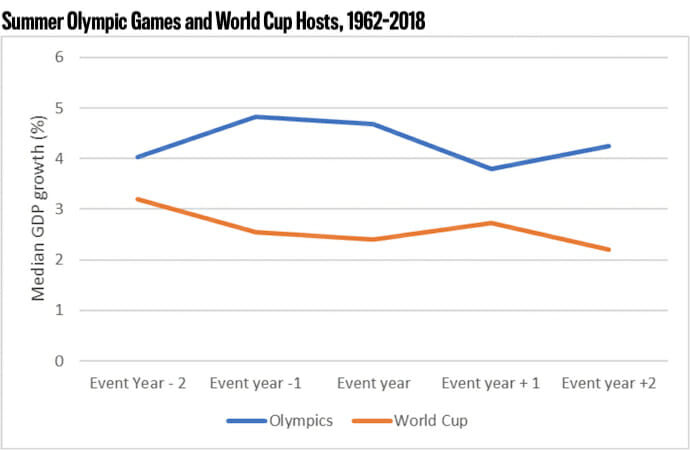

The massive nature of the events means that national governments play a key role in preparing for the Olympics and World Cup. And like the winners of the global and continental football tournaments, the hosts do not seem to do so well out of the events. When looking at GDP growth for host countries since the 1960s, there is little sign of an economic boost in the form of increased growth in the year the Olympics or World Cup is held; and in the case of the Olympics, growth slows down the year after. At the same time, it may be that the slowdown comes after several years of preceding and heightened growth to prepare for the event (Figure 2).

Although dispiriting, such findings do offer some silver linings. The immediate one is that Tokyo is not alone. The expected losses that it will incur this year are in line with the experience of other former hosts. The other is that this should be taken onboard by future hosts and candidate cities. Rather than pursue unrealizable goals, they should treat being the host of the Olympics or the World Cup for what it is: the opportunity to enjoy several weeks of elite sporting excitement and which advertises their country into the bargain. Of course, the trade-off is whether spending vast amounts of public money on a one-off event is worthwhile. But that would be a more honest discussion than whether it will lead to a legacy that includes economic growth.