Tech

Yuri Gagarin in Space: the Politics of Cosmic Discovery

Aristotle thought notions of humanity as a supreme species atopos – absurd. In contrast, the Romans had a very defined term that distinguished humans as humans, impressive relative to other species: humanitas. Hannah Arendt, in considering these contrasts in “Man’s Conquest of Space,” a piece penned for the American Scholar (Autumn, 1963), turned her mind to those questions that remain, more broadly speaking, the staple of inquiring minds: “Has man’s conquest of space increased or diminished his stature?”

A difficult question indeed, especially for a species distinctly obsessed by anthropomorphic elements. While scientists like Max Planck urged that these elements be excised from the human imagination, the political and legal imagination was always going to be even less worthy. The scientific mind is naturally inquiring and expansive, the political-legal often opportunistic and calculating.

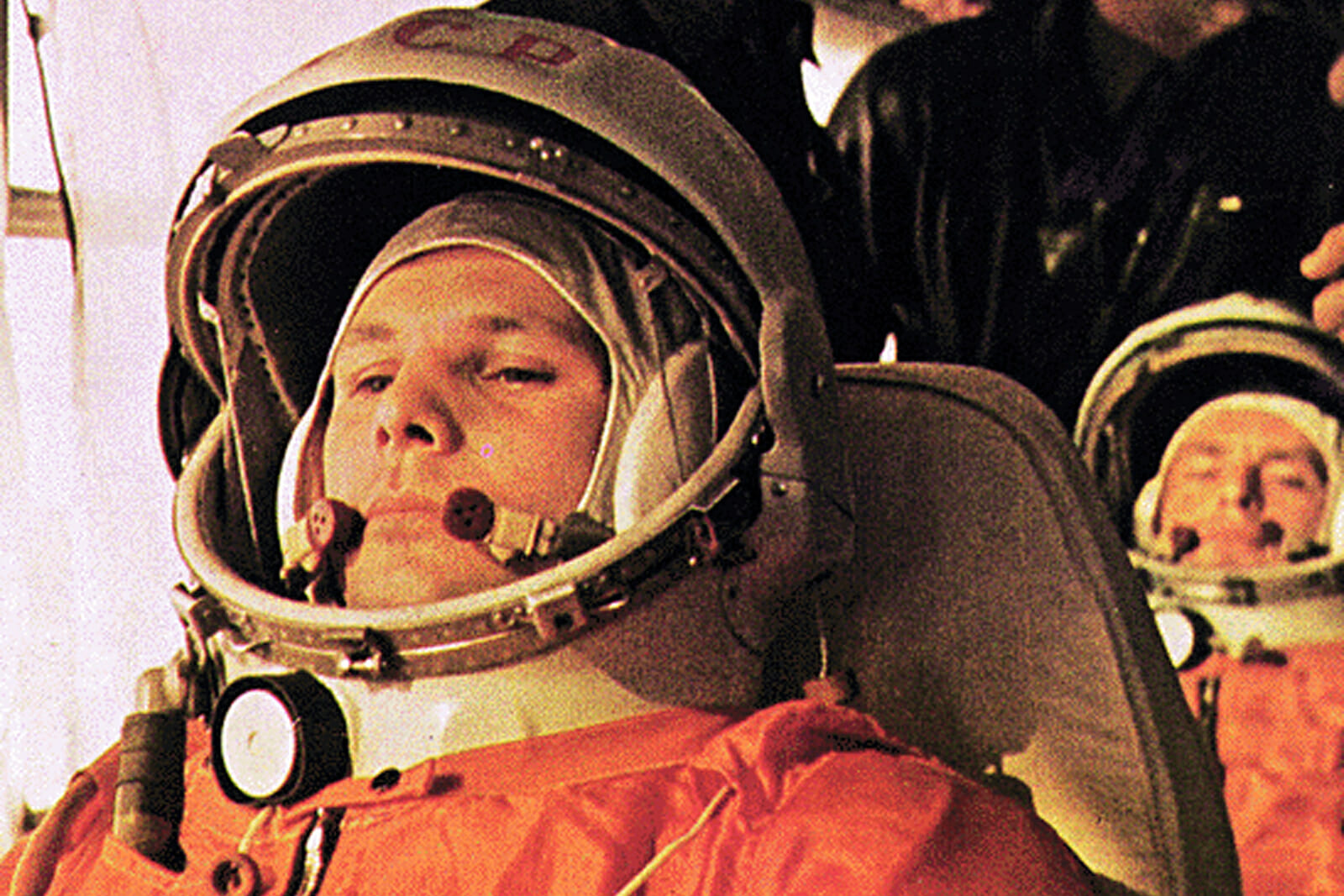

Not only were humans to be worshipped as the new navigators of the extra-terrestrial world after Yuri Gagarin’s April 12, 1961 flight into space; they would also be politicised, the daring heroes of races and countries keen on getting points up on each other.

The feat engendered both terror and delight – science, appropriated for suitable political ends, had been brought into space like a boisterous statement of Soviet prowess and intent. Those in Freedom’s Land were concerned that the dark Soviet machine had advanced with unstoppable menace. This was not what a supposedly primitive culture was supposed to do.

Even before Gagarin became the first human to make it into outer space (Russian conspiracy sites on this differ, claiming several unacknowledged cosmonauts), the ground, or in this case, celestial space, was already going to be the challenge. The Soviet Union had launched SPUTNIK 1 in October 1957. With inexorable logic, humans would follow. On February 25, 1960, twenty air force pilots between 25 to 35 were selected.

The return of those selected was hardly promising. Of the first 20, only 12 would fly. Eight never made it to space. Two engaged in a drink-fuelled brawl that led to their dismissal. Another was injured on being exposed to 8G in a centrifuge test. One also committed suicide.

With such blotted paper, the Chief Designer of the Soviet space program was relieved to hit upon Gagarin, deemed reliable and capable. On an adapted and refitted ICBM R-7 rocket, the young Soviet cosmonaut made a journey of Columbus-styled dimensions, even if his journey remained a puppeteer-directed effort on the part of ground control.

Cold War envy and fears did not make the announcement a pleasant one in the United States. First SPUTNIK, now this. “Just tell me how to catch up,” pleaded US President John F. Kennedy. “Let’s find somebody. Anybody. I don’t care if the janitor over there has the answer, if he knows how.” Knowledge moves in baffling ways indeed.

In May 1961, Alan Shepard became the retaliatory instrument of the US space effort, one that became known as the Mercury-Redstone 3 mission. Rather less impressively, he made it to 187 km above the Florida coast in an unspectacular 15 minute journey that involved no orbit.

Notwithstanding this, both men had been the guinea pigs of the broader scientific and political experiment on how far humanity could make it into space. It was true that strides were made in space biomedicine and linked sciences, but lurking in the background was the miasma of political motivation.

Legal squirreling and speculating was also taking place at the time. Having put humans into space, jurisprudence was called in to make claims and contentions about the next frontier of legal briefs and battles, the next ground of disagreement and rivalry.

“In certain quarters,” claimed a smug Jacek Machowski, counsellor to the Polish Mission to the United Nations, “there still prevails an erroneous opinion that the conquest of outer space by man constitutes an exclusive domain of science and technology” (Proceedings of the American Society of International Law at Its Annual Meeting, Apr 27-29, 1961).

Gagarin’s orbit did not merely open the heavens to human intrusion. It also opened them up to human contest requiring, according to Machowski, “cooperation of experts in different fields, including law and politics.” He would conclude with the now accepted notion that actions in space “taken by a state in outer space against the sovereignty and territorial integrity of other states” would be violations of the UN Charter “and a serious breach of international law.”

The observation provided Leon Lipson of Yale Law School in the same proceedings a chance to ponder whether reconnaissance space satellites were legal or otherwise. Scientific space inquiry for its own sake was the least of his concern.

Should Gagarin, he posed, be considered an enterprising celestial pushing Charles Lindberg, or more along the lines of Francis Gary Powers, a US pilot shot down in his CIA U-2 spy plane over Soviet airspace the previous year? “Both Powers and Gagarin flew over territory not within the jurisdiction of the government that sent them on their missions.” And so the reductionist arguments continue.

In the 55th year after Gagarin’s outer space journey in a Vostok 3KA-3 spacecraft, the Russian Space Agency proclaimed it “The Year of Yuri Gagarin.” Russian Roscomos released a statement as an open call to human curiosity. “We invite all those who are interested in space, dream of distant planets and those for whom Russia’s space activities are a part of life to join us.”

Reverting to type, however, the declaration of the year of Gagarin does come with its inescapable political import. Space is prowess, and challenging the heavens continues to be good for morale, and prestige on the ground.

On April 28, the Soyuz-2.1a carrier rocket was launched from Vostochny Cosmodrome in Russia’s Far Eastern Amur Region. The reason? To wean off Russia’s dependency on the Baikonur space centre in Kazakhstan, a venue that is being leased until 2050. Going into the cosmos was, and remains political.