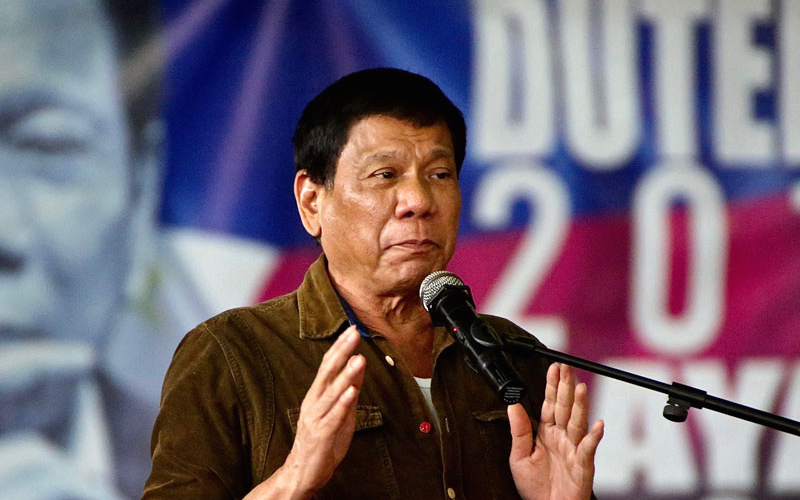

Duterte and ‘The System’

The people of the Philippines have spoken and Rodrigo Duterte is the presumptive president-elect. Based on the size of his victory, the electorate has clearly had enough of crime-ridden streets, rampant corruption, nepotism, political circuses, and business as usual. They have elected a man who has promised to clean it all up. Citizens of many others countries have said — or are in the process of saying — the same thing, from Argentina and Brazil to South Africa and the U.S.

A global political backlash against entrenched interests and being held hostage by criminals is under way, and that is good. It begs the question, even if Duterte is successful in ending criminality in the Philippines by “killing all criminals” over the next six years (which appears to be what the majority of voters want), can he also clean up ‘the system’? And, if he fails to do that, will it all matter once he leaves office? After all, the Philippines has a history of backtracking on progress made once a new president takes office.

Things must be pretty bad if a man who endorses and participates in vigilante-style justice and summary executions led by death squads is overwhelmingly elected by the people to do so on a national level. Duterte, a tough-talking, profanity-laced mayor from the southern city of Davao, who many analysts portray as Asia’s version to Donald Trump, is unlike Trump in that he is praised for his record of “getting things done” – as a mayor. He has now been catapulted to the presidency — his first national-level position.

Anyone who knows the Philippines understands how dangerous it can be to live there, but, by all accounts, crime has become truly intolerable in recent years. By the Philippine National Police’s own admission, there was a 46% rise in crime nation-wide in the first half of 2015. The economic boom of the Aquino years has been accompanied by a rise in crime among those who have been left behind – those at the bottom of the economic ladder. Life doesn’t get better for them, no matter who is in Malacañang Palace.

So, how does a president solve that problem? For all the economic progress that has been made during the Aquino administration under Daang Matuwid (straight path), the incidence of poverty remains virtually unchanged — at 25 percent since 2009. While the unemployment rate has dropped from 7.3 percent (in 2010) to 6.5 percent (in 2015), the under-employment rate stayed virtually flat during the same period, at approximately 18.5 percent. Even if Duterte (otherwise known as “Digong,” “The Punisher,” and “Duterte Harry”) were to assemble, arm and sanction an army of people to ‘wipe out’ drug dealers, terrorists, criminals, pimps and prostitutes (among others), what will that do to resolve the country’s structural problems – of which there are many? He argues (wrongly) that solving the criminality problem will be the solution for everything else, presuming that what worked in Davao will work on a national level. Perhaps he also believes in the tooth fairy.

Duterte has said he intends to ‘devolve’ power from Manila to the provinces and change the government from a unitary system to a federal parliamentary system. Well, devolution hasn’t worked so well in countries such as Indonesia, which has experienced a range of problems from the devolution plan it has attempted to implement over the past couple of decades. As the International Crisis Group has noted, in empowering local officials, devolution sometimes ends up empowering the most regressive, corrupt, and undemocratic local politicians, who use their local influence to stymie national-level courts, regulations, and politicians who often are devoted to more constitutional, liberal applications of the law. Without concurrent reform in the political party system, passage of an anti-political dynasty law, and greatly enhanced systemic transparency, the same is sure to become true in the Philippines. Also, is Duterte likely to end up being victorious in devolving power against the country’s incredibly powerful billionaire families, who are estimated to control as much as 80 percent of the Philippine economy? No way.

Duterte wants to reform the country’s tax collection apparatus to collect more taxes and enable him to have greater financial resources to spend on other planks of his platform. It is worth noting that under outgoing president Aquino, government tax revenue as a percentage of GDP remained below the 20-year average of 14%, in spite of his pledges to significantly increase tax revenues at the outset of his term. If Aquino was unable to achieve his objective with strong economic tailwinds at his back, is it likely that Duterte will be successful in doing any better – particularly as many economists expect a global recession to begin in the coming months? We don’t think so.

The president elect also wishes to enhance the country’s economic competitiveness, which would be a very good thing. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), the Philippines’ competitiveness ranking jumped by 7 slots, from 52 in 2013-2014 to 59 in 2014-2015. The country’s gain of 33 places since 2010 is the largest over that period among all countries studied, the WEF said. That said, the Philippines has done rather poorly in the World Bank’s (WB) Doing Business rankings, which judges the desirability of doing business in a country based on 10 key indicators. According to the rankings, the Philippines slipped 9 places (out of 189 countries) from 86th in 2014 to 95th in 2015 (the lower the score being better), and another 8 places to 103rd in 2016. The Philippines actually declined in 8 of the 10 indicators in 2015 and in 9 of the 10 indicators in 2016.

So while, according to the WEF, the Philippines is becoming more competitive, according to the WB it is becoming less desirable as a place to do business – a rather strange dichotomy. We believe Duterte would be best advised to concentrate on changing the perception of the country as an undesirable place to do business, as a starting point. In the WB rankings, the country scores in the lowest quartile in starting a business, protecting minority investors, and enforcing contracts. Creating a streamlined approval process should be a first order of business for him, but over the longer haul, reforming the judicial system so that it treats foreign and minority investors fairly, and enforces obligations under legally binding contracts should be a priority. That means tackling corruption head on throughout the judiciary system. Doing so would surely do wonders to change investor perceptions, but would surely also rank among the most difficult of tasks. If Duterte were able to translate gains in attaining order in the streets into meaningful change in the country’s judicial and legal institutions it would bode well for the country and international business community alike.

Aquino has made good progress in tackling corruption in government. In 2010 the Philippines was ranked 134th out of 178 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. The country’s 2016 ranking is 95th (out of 168 countries), tied with Armenia, Mali and Mexico. Another pillar of changing investor perceptions should be to tackle endemic corruption throughout society – a tall order for a scourge that plagues countries throughout the world. While addressing corruption in government is a great place to start, the real challenge is to tackle corruption starting from the bottom. Anyone who has visited the Philippines knows that it is common practice among workers at all levels of the private and public sectors to try to game the system and/or add a little something ‘extra’ for themselves. If Duterte really wants to make a difference, he’ll find a way to nail that practice.

The question now is what kind of a president Digong will be, and whether his presidency can meet the plethora of needs of a country yearning for meaningful and lasting change. Despite his tough talk, and based on his newest “8-point economic plan,” he has thus far suggested no new change in economic policy and seems content merely “copying” the platforms of former presidential candidates. What is needed, in order to achieve what we are recommending here, is fresh, bold thinking. Cookie cutter approaches are not going to get the job done. If Duterte really wants to be remembered as a game changer, he needs to shake the system up, from the top to the bottom. Only time will tell whether he is capable of, or interested in, doing that.

This article was originally posted in The Huffington Post.