Rio’s 2018 Carnival got Political, and it was Amazing

This year, Rio’s world-famous carnival parade took a remarkable turn. The parade is in fact a competition between different community organizations, known as samba schools, as to who can put on the best show.

But this year’s champion, the Beija-Flor samba school, took a decidedly different and gutsy approach by presenting a scathing criticism of the social problems plaguing Brazil and their historical root causes. It was a master class of using art to tell the truth. And in this case, the truth hurts.

Beija-Flor’s presentation used as its anchor the 200th anniversary of the publishing of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. A more traditional parade would have depicted some aspects of the author’s life and the plot of the story, but in these times of extraordinary turmoil in Brazil, Beija-Flor decided to use Frankenstein’s monster as a metaphor for Brazil. In this way, they used their platform as one of the nation’s foremost artistic institutions to tell some hard truths about Brazil’s social problems and their historical causes.

The metaphor of Frankenstein’s monster is that of a creature that is made from scraps, and because of its different appearance, is considered hideous and scary, and is subsequently abandoned. This is a reference to Brazil’s diverse make-up, a country populated by exploitative colonists and the few native peoples who survived them, by African slaves, and by subsequent waves of immigrants from Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

It is also a reference to its colonial exploitation by Portugal, as well as the legacy of slavery and the inherent structural and systemic racism that persists amid government corruption and incompetence. In the metaphor, Brazil is abandoned not once, but twice. First by the Portuguese colonizers, who stripped the country of its natural resource wealth, and now by the Brazilian political and business leaders who have followed in this tradition by committing acts of graft and corruption, culminating in the historic multi-billion dollar Petrobras corruption scandal that has embroiled the country in recent years, taking down presidents and the economy. It is a story of a small group of exploitative and powerful people living in lavish wealth while the people languish in poverty, and it is a story that has been retold countless times throughout the country’s history.

Here are some of the highlights of this truly remarkable presentation that has reverberated through Brazilian society.

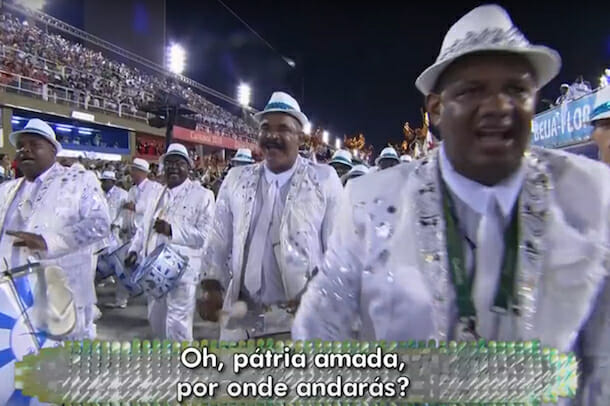

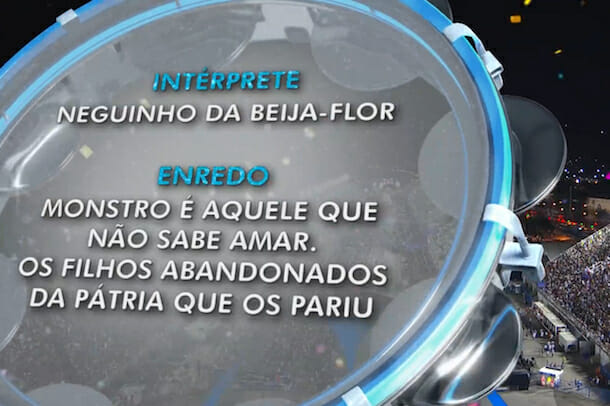

Implicit in the Frankenstein metaphor is the question, who is really the monster here? The answer is in the title of the samba song, the enredo, backing this year’s presentation: “The monster is the one who does not know how to love: The children abandoned by the home land that gave birth them.”

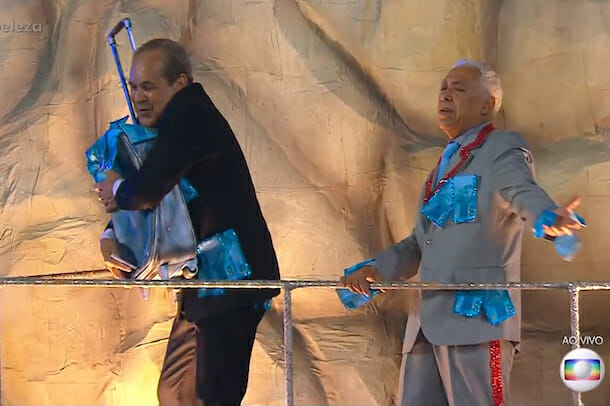

The parade opens with a bad omen, a black feathered bird. Then, amid icebergs, a boat appears carrying Dr. Frankenstein. This is how the book begins, with the doctor narrating his story to the ship’s captain. The ship then opens up and transforms into the laboratory where he created the monster.

And here begins the metaphor to Brazil’s history. The lab is followed by a parade of pirates, representing the pillaging and exploitation of Brazil’s resources from the very beginning of its history.

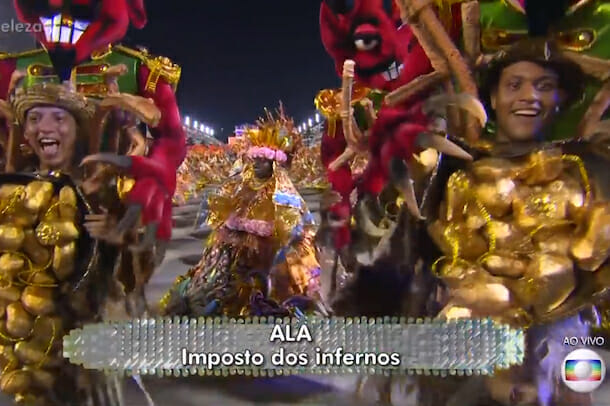

Red faced devils are depicted carrying off gold — representing “Taxes from Hell,” specifically the heavy taxes paid to Brazil’s colonial overlords in Portugal on the gold extracted in these resource-rich lands. These are followed by women dressed as hollow-bodied saints, a reference to a practice in which wooden figures of saints were hollowed out and filled with precious stones to be smuggled from Brazil.

Both depict how Brazil’s natural resource wealth was systematically stolen from the beginning of its history.

Then, the colonial courts are called depicted as splendidly dressed mice, representing their leeching of Brazil’s wealth, living in privilege off the extraction of resources done by slaves.

There are references to Ali Baba and his thieves, as well as blood-sucking vampires.

Next, the allegory transitions to modern times. Dancers dressed in black, with skulls on their heads, representing “black gold,” a reference both to petroleum as well as to the massive graft scandal at the national Brazilian oil company, Petrobras. It is a symbol of corruption and greed unchecked.

Besuited rats and wolves in sheep’s clothing carrying briefcases full of cash represent greedy and corrupt government officials.

There is even a scene depicting a banquet where diners in suits wear cloth napkins on their heads, a reference to a photo of former Rio governor Sergio Cabral taken at a fine Parisian restaurant a few years ago.

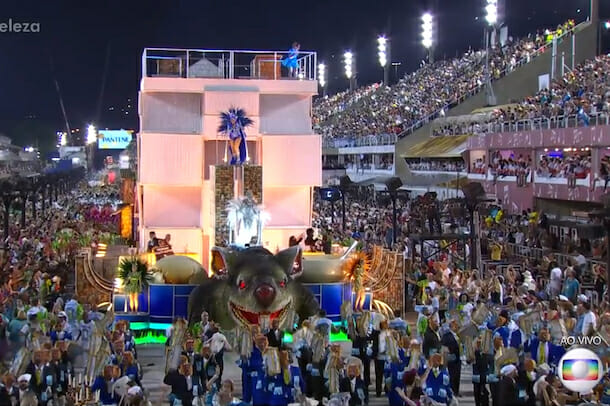

Next, a multi-tiered float represents the current corruption on political institutions and its consequences on society. Incarcerated drug dealers are shown continuing to command the narco trade from prison, talking on smuggled-in cell phones.

The predominantly black and poor prisoners languish in subterranean dungeons, while white-collar criminals live out their sentences in relative comfort upstairs. This is a reference to the custom-made prison facilities built to house politicians charged with corruption. In other cases, they don’t have to go to prison at all, and get to stay on house arrest. To represent this, elegantly dressed people are shown wearing ankle monitors and eating pizzas, a reference to things “ending in pizza,” a Brazilian expression for politicians always getting away without any consequences.

Above the prison in this float are the Petrobras company headquarters, as well as the national congress building, which are being carried by a giant rat, representing greed. Owners of the country’s big infrastructure development companies, many of which have also been embroiled in graft scandals involving inflated government contracts, are shown carrying suit-cases of cash. The Petrobras building then transforms into a favela, a reference to the consequences that Brazil’s systemic corruption has on the population, who is forced to live in squalor, poverty and fear of violence due the malfeasance of political and business leaders, despite the country’s wealth.

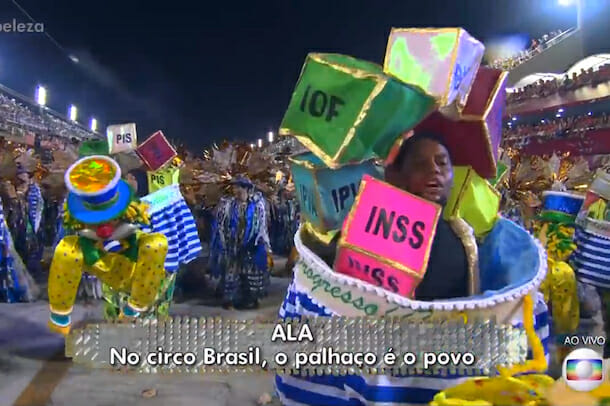

The people are depicted as clowns in the circus that is Brazil, carrying on their shoulders the weight of taxes. Brazil has one of the heaviest tax burdens in the world, yet little to show for it — a constant refrain is “taxes like Scandinavia, infrastructure like Africa.” Brazilians are made into fools for paying so much into the system and then watching their money being stolen or lost to inefficiency and incompetence.

The consequences of this malfeasance and mismanagement are also addressed, such as the environmental toll that breakneck development and resource exploitation have taken on the environment. There are refugees of drought, migrants from Brazil’s arid northeast who migrate to the south in search of the “promised land” in Brazil’s larger cities.

There are images of pollution, and of people dressed in rags rummaging through garbage.

The social consequences are visible in the city’s streets, and as the parade continues, street dwellers are shown begging for money on church steps, and children are on the streets begging instead of going to school.

There is then a depiction of the state of the Brazilian public health system, which are death and the grim reaper carrying staffs entwined with winged snakes, a symbol of medicine with origins in Greek mythology.

Next, soldiers in fatigues carry representations of the favelas on their backs, symbolizing the military occupation of the favelas in the fight against narco-traffickers and the brutality that has accompanied it, as well as the civil war being fought on the streets and constant violence and lack of security that regular people have to deal with.

A float called “abandonment” depicts stray bullets, injured police officers, dilapidated schools where students are victims of gun violence, and dismal conditions in public hospitals where patients die in hallways waiting for treatment. There are street dwelling children dressed in rags picking through garbage.

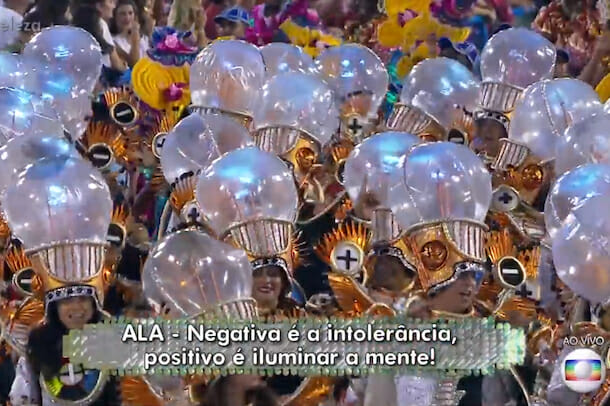

Drawing on these images of suffering and squalor, the parade continues by addressing the rising intolerance in Brazilian society, specifically discrimination based on religion, race, gender, and sexual orientation.

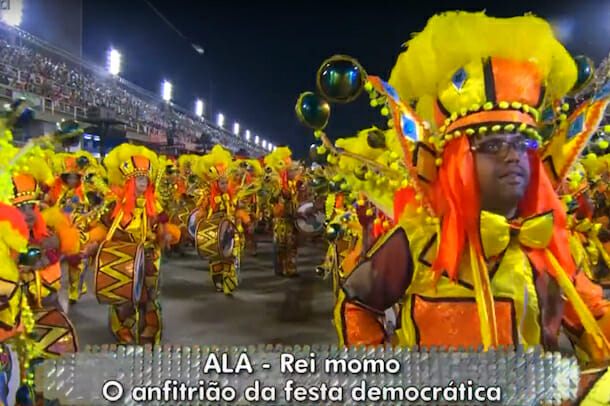

To end the parade, things take a positive turn, with representations of hope, redemption, and peace.

In the quest to make their country better, the people take to the streets in protest.

The final float features a triple pietá, depicting several different scenes. The first is the final scene from Frankenstein, in which the creator is dead in the arms of the monster. The monster weeps and says, “I only ever wanted to be loved.” The other two pietás depict scenes of contemporary Brazilian tragedy: A mother holds her dead police officer son, another holds an emaciated child dead of hunger. The meaning of the last float is “learning how to love.”

It was a fitting end to the carnival celebrations. Beija-Flor was the last samba school to parade, and as it left the Sambadrome, a sea of people poured down from the stands and continued to follow the carnival floats down the street, spontaneously singing the samba song whose lyrics touched a nerve, and their hearts. It was a repressed lament that Brazilians have been holding in for years as they watch their country implode. It was an exorcism, a catharsis. A powerful and moving testament to the difficulties that Brazil is living through, and has lived through for all of its history, expressed through the splendor of that most Brazilian of art forms, the world-famous Rio carnival. A true reflection of the notion that samba may be joyful, but it is the child of sorrow. And that it is transformative. It was a moment of healing for a suffering country.

This article was originally posted in Medium.