Health

Healthcare Costs are Harming U.S. Competitiveness

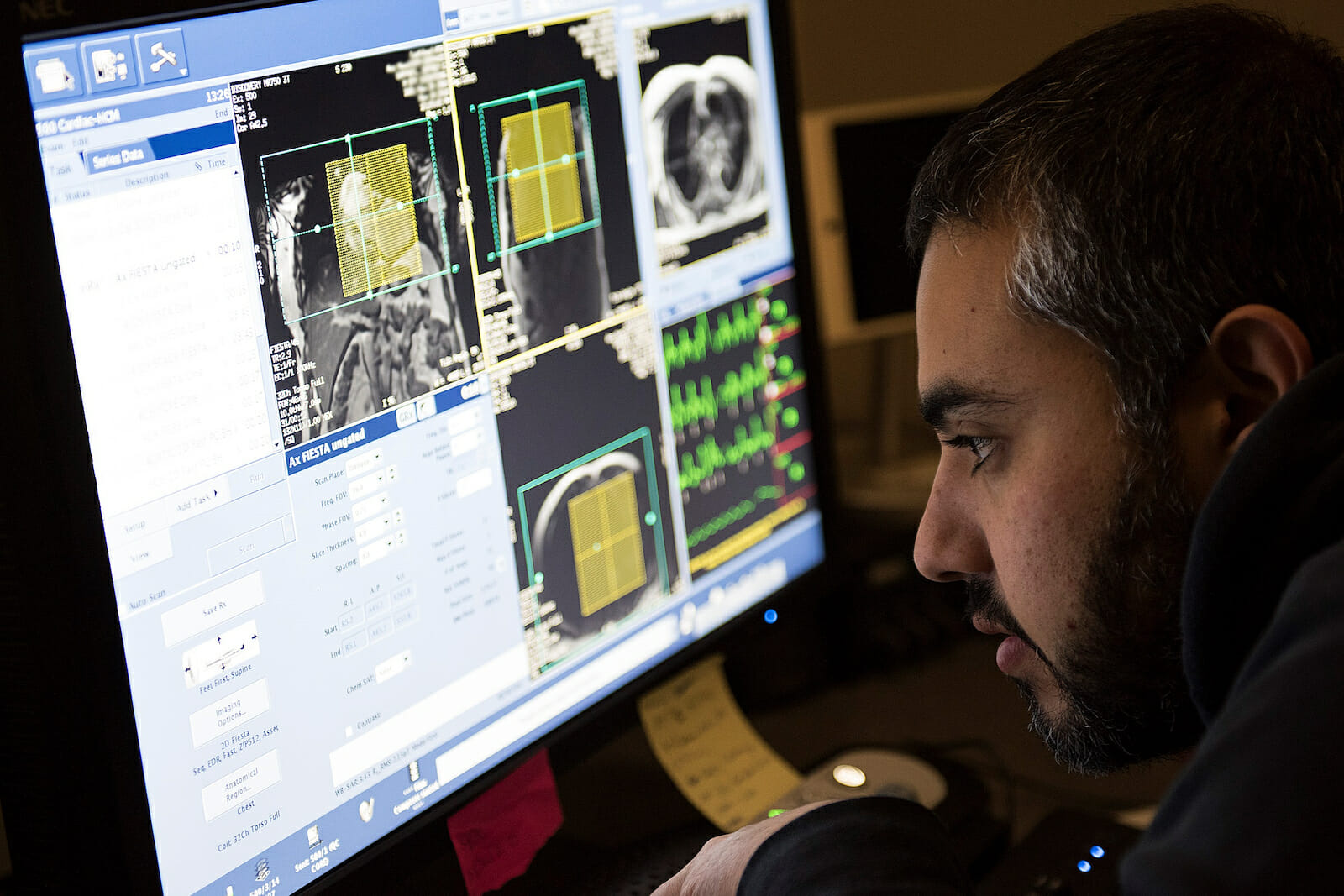

Back in September 2016, Elodie Fowler, a 3-year-old little girl, slid into an MRI machine so doctors could get a better understanding of her genetic condition that was causing the right side of her body to swell and eat regular food.

The scan took about 30 minutes. Afterward, the hospital’s doctors used the results to put Elodie on a new drug regimen to help alleviate the swelling and help her eat.

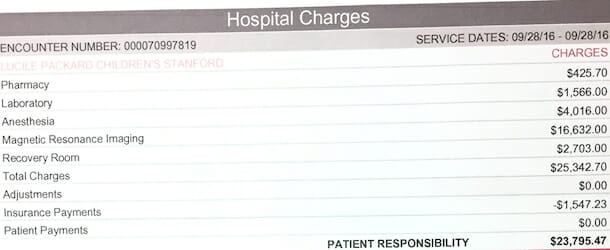

Elodie’s parents knew their child’s care would cost them a few thousand dollars, a substantial amount of money. Still, they thought they had done their homework. They researched the price of typical pediatric MRI scans. They knew they were out-of-network, but figured their insurance plan would cover half of a “fair price” MRI. What happened several months later shocked them:

A few months later a bill totaling $25,000 arrived in their mail. Their insurance only paid $1,547.23, leaving the family on the hook for the remaining difference: $23,795.47.

A few months later a bill totaling $25,000 arrived in their mail. Their insurance only paid $1,547.23, leaving the family on the hook for the remaining difference: $23,795.47.

Stories like the Folwer family are very common in the U.S. According to Sarah Kliff, the reporter who wrote about Elodie’s story, “I find myself writing about $25,000 MRIs, $629 Band-Aids — even a $39.95 fee just to hold one’s own baby after delivery. People send me these types of bills quite regularly via email.” According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, about 20% of Americans have substantial medical debts in a given year.

Outrageous healthcare costs are enormous burdens for families like Elodie’s parents. Costs are also an enormous burden for employers too. According to the Kaiser Foundation’s 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey, a single coverage plan generally costs about $6,700 per year. Most people get some form of family coverage, however, which costs, on average, about $20,000 annually, with employers picking up about $14,000 and employees paying the difference. And costs don’t include additional factors like out-of-pocket expenses, deductibles, etc.

U.S. companies are burdened with the enormous cost of providing health insurance for their employees, a stark contrast to our international competitors like European businesses. The reason for this is because healthcare in Europe is financed by broad-based consumption taxes that do not fall on businesses. Furthermore, the Value-Added Tax (VAT) is rebated at the border on exports, meaning the tax does not raise the price of exports. Because of these two factors, European exporters are very competitive relative to those in the U.S., where many taxes cannot be rebated (e.g., the corporate tax) and therefore reduce international competitiveness.

The complexity of our healthcare system is an enormous burden on people in additional ways. For example, consider the testimony of business owners like Gene Marks:

“At my company — and most other small businesses — we spend a significant amount of time figuring out how to minimize our health-care costs.

We strategize with our outside benefits people. We consider alternatives like self-insurance and joining associations. We set up health and flexible savings accounts. We spend time and money administering these plans.

Then, we worry every year what the next year’s increase will be in what is one of the most significant line items on our income statement: ‘Health-care costs ‘only’ rose 5 percent this year. Yay!’”

Mr. Marks isn’t alone in his assessment. U.S. companies spend more than $620 billion annually, which puts a severe drain on a company’s resources. According to a Harris Poll commissioned by Castlight Health, about 90% of chief financial officers interviewed agreed they would raise their employees’ wages and invest more in their businesses if their company’s healthcare costs were lower. Finally, the surveyors overwhelmingly (93%) agreed that our country’s abnormal healthcare costs give foreign companies a competitive advantage.

Because of our inefficient public-private system, U.S. companies are incurring a “triple tax.” First, they pay into programs like Medicare via payroll taxes. Second, they pay for insurance programs via health benefits. Because Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements often do not match the total costs hospitals incur, however, they pay higher insurance programs to make up for the difference. Third, as medical practitioners do not work for free, employers subsidize the costs of treating America’s uninsured, again via higher insurance premiums. In 2016, community hospitals provided more than $38.3 billion in uncompensated care to their patients.

All these concerns raise one simple question: Why are healthcare costs so high relative to other countries? According to Kevin Drum, the roots of our inflated healthcare costs stem from aggressive rent-seeking by the medical industry starting back in the 1970s:

“Massive increases in health care spending are neither normal nor inevitable. Until the late 70s, medical inflation ran at about 1-2 percent above overall inflation. Then, for nearly two decades, we suddenly went nuts and allowed every player in the health care industry—doctors, hospitals, drug companies, device manufacturers—to go on a wild spree of increasing their prices as much as they felt like. Being a physician changed from being a comfortable, upper-middle-class occupation to being a member of the top 2 percent. Hospital CEOs got rich. Pharmaceutical companies introduced rafts of new medications and discovered they could charge whatever they wanted and no one would stop them.

Finally, in the late 90s, the party ended. We all woke up to discover that an entire sector of the economy had grabbed an extra trillion dollars for itself for no particular reason except that they could get away with it. So we finally got serious about reining in health care costs, and we did. Medical inflation went back to 1-2 percent above overall inflation and lately it’s been even lower than that.

Unfortunately, the crazy years pushed prices permanently higher. So year in and year out, the health care industry still gets their extra trillion dollars. We’ll probably never claw that back. But at least it’s not getting any bigger these days.”

The healthcare industry’s rent-seeking has had enormous implications for the economy. For example, a 2009 RAND study indicated U.S. industries with the highest level of employer-sponsored healthcare showed slower growth in both employment and contribution to GDP between 1987 and 2005 compared to industries where health benefits were less common. According to Neeraj Sood, lead author of the study and RAND senior economist, “This study provides some of the first evidence that the rapid rise in health care costs has negative consequences for several U.S. industries.”

The healthcare industry’s rent-seeking needs to come to an end. We’re all in this mess together, and everyone needs to come together to purge the parasites that are hindering U.S. competitiveness, undermining workers’ wages, and placing enormous burdens on U.S. businesses. If not, we’re all screwed.