The 25th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall: An Event to Commemorate not Celebrate

This 9 November marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. On that day in 1989, as much as today, it marked the passing of history, not an event to celebrate. In August of 1961, the construction of the Berlin Wall provided a practical means to resolve or, at the least, to de-escalate one of the greatest causes of superpower confrontation on the European continent, and assuaged the security concerns of the European states. By 1989, the Berlin Wall had served its purpose; its time had come to an end. Nevertheless, one is not to countenance the individual acts of barbarity that it had occasioned. Let no one forget the nineteen year-old Peter Fechter, in 1962, shot and left to bleed to death at the base of the Wall by the Volkspolitzei, the People’s Police of the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

The German Question in 1961 and European Security

Whereas in 1955, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States had concluded successfully the Four-Power Occupation of Austria, they had failed to do so with Germany. The case of Austria was much simpler. It was smaller and mountainous. It consisted in the unification of four occupation zones, the prohibition of any unification with Germany or the return of Habsburg rule, and its permanent neutrality, i.e. its exclusion from either the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) or the Warsaw Pact. As such restrictions were acceptable to the Four Powers, so too were they acceptable to Austria’s neighbors, and the overwhelming majority of Austria’s citizens. Furthermore, the Austrian question was far less politically and strategically charged than that of Germany.

With the exception of mountainous regions of Bavaria, the Germany under the occupation of the Four Powers was in the same flat region, particularly on the northern plain, with no areas of salient points of elevation between the Atlantic Ocean and the Soviet border. It had ideal conditions for tank warfare, the essential part of land combat that had come of age in World War II.

This characteristic alone merited special treatment by the Four Powers and the interest of Europe. By 1961, there stood the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) and the GDR: two armed sovereign states, members of opposing military alliances and economic communities, the former a member of NATO and the European Economic Community (EEC), the latter a member of the Warsaw Pact and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). Any change in the status quo was unacceptable without major revisions of the operating regime for European peace, where a final settlement of post-war borders was still fourteen years away with the Final Act of the Helsinki Accords. All European countries were opposed to a united and uncontrolled Germany; they had lived through the horrors that it had wreaked. A united and neutral Germany was anathema to the F.R.G. and the West; a united and allied Germany was unthinkable to Four-Power consensus. The viability of the G.D.R. in the current regime was a sine qua non to European security.

Berlin: A Synecdoche for Four-Power Accommodation

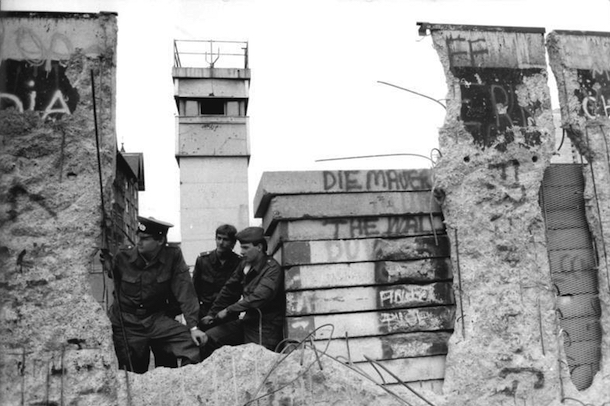

West Berlin had been a constant source of irritation to the Soviet Union. West Berlin was one hundred miles inside the GDR. British, French, and United States troops were present, as they had a legal right to be so under the accords signed by the Four Powers. The accords allowed them three highways from the FRG and air corridors.

The Soviet Union saw West Berlin as a base for activities inimical to the GDR, the Soviet Union, and the Warsaw Pact, especially as a center for espionage.

In late 1940s, the Soviet Union maintained an eleventh-month land blockade to be foiled by Western resolve with an air bridge of the continuous resupply of vital resources to West Berlin. Later, the Premier of the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev, in masking his annoyance with bluster and a nod to West Berlin’s vulnerability, reportedly quipped, “Berlin is the testicle of the West. When I want the West to scream, I squeeze on Berlin.”

Both in 1958 and 1961, he presented ultimatums demanding that Western troops vacate West Berlin and that it become a demilitarized free city. On both a geopolitical and a legal basis, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States rejected Khrushchev’s demands. The post-war occupation had not ended; no final peace had been concluded. The Soviet Union, as too the three Western Occupation Powers, faced an additional challenge as West Berlin had become a threat to the G.D.R.

By 1961, the GDR was suffering a severe population loss; 3.5 million citizens had left, approximately 20% of the population. This was a strong blow to the economy, as a heavy share of the émigrés was young professional and skilled workers. The border between the F.R.G and the G.D.R. was closed. As Berlin was under Four-Power occupation, since 1953, the East-West sector crossings had become free points of exit for citizens of the G.D.R. The Chairman of the State Council Walter Ulbricht wanted to close the loophole through which the state was losing its human capital, but as it was Berlin, he could not do it without Soviet approval. Khrushchev understood the problem, but was chary to do so knowing the embarrassment that it would create as he was courting Third World and Western opinion. Perhaps two factors led him to assent to Ulbricht’s wishes.

The problem was growing worse; the GDR was losing an average of 2000 people a day. Once again, Khrushchev met Western intransigence when he repeated his 1958 Berlin ultimatum at the June Vienna Summit with the United States President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Although undesirable, a wall seemed to him congruous with his goals and threatened not too severely his relations with his fellow Occupying Powers. Less than two weeks before the beginning of the building of the Wall on the night of Saturday, 12 August, and Sunday, 13 August, as if to give credence to his perceptions, the Chairman of the United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee J. William Fulbright said “I don’t understand why the East Germans don’t close their border, because I think they have the right to close it.”

If Khrushchev’s reasoning was in fact so, future events proved him to be correct. In the middle of August, the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan found nothing illegal in the Wall’s construction; Kennedy said to his aides, “It’s not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.” Nevertheless, to assert the Western Powers’ legal rights in Berlin, Kennedy sent Vice President Lyndon Johnson to arrive in West Berlin to meet on the next Sunday the First Battle Group of the United States 18th Infantry of 1,500 soldiers carried by 491 vehicles, which had crossed the GDR on one of the Berlin Accords’ designated highways to augment the already present three brigades of the Western Occupying Powers. Just over two months later in Berlin, from 17:00 of 27 October till 11:00 of 28 October, Soviet and United States tanks faced each other in battle-ready conditions. The confrontation was resolved peacefully and confirmed the dominance of Soviet and Western rights, each to its respective zone of the city. The Four Occupying Powers had maintained the status quo of the occupation and lessened the volatility of Berlin as an impediment to its continuation. They had restored the trust of all that there was not to be soon an unoccupied and united Germany.

Germany, Europe, and the World

By the summer of 1961, only sixteen years had passed since Germany’s defeat. Europe had not recovered from Nazi aggression. Europe had borne great hardship in the sixteen years following the war. Much of the basic infrastructure had to be rebuilt. British food rationing had been maintained until 1954, in part to keep the British occupied areas of Germany from hunger. The economic burden was but a part of what Europe had suffered. Nazi Germany had maimed, tortured, or killed, and in some cases all three, great percentages of populations of the states that it had victimized. It had killed systematically two-thirds of all European Jewry.

Still, many of those responsible had not been tried and considered it all too probable that they might live in impunity, and perhaps do so openly. Many of them were still young enough to have long years ahead of them, but old enough to have gained or still have retained positions of authority. In the German diaspora, there were many Nazi fugitives for whom a united and unoccupied Germany may have become a safe haven or a source of succor. In spite of the criminal prosecutions in the FRG and the GDR, political expediency and strategic exigencies, especially those of their respective dominant allies, the United States and the Soviet Union, sometimes trumped the judicial process. Both the FRG and the GDR were paying reparations, or continued to reject their payment, as did the GDR to the State of Israel. The Berlin Wall for its 28 years provided the hope that German collective and individual responsibility, and future action would not be left jointly or separately solely to the FRG and the GDR.

After the Berlin Wall came down 9 November, 1989, the FRG’s Chancellor Helmut Kohl felt somewhat miffed at British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and French President François Mitterrand’s lack of joy upon receipt of the news. Mitterrand and Thatcher knew too well Germany’s crimes during their adult lifetime. The FRG’s possible annexation of the GDR was a source of trepidation and concern. Thatcher’s Private Secretary for Foreign Affairs Charles Powell wrote, “The Prime Minister says that Chancellor Kohl has no sensitivity toward the other countries and seems to have forgotten that the division of Germany was the result of a war that Germany had started.”

Commemoration not Celebration

Perhaps best said, the Wall collapsed on the night of 9 November, 1989. Both the need and the energy to maintain it were gone, so too were the conditions that had led to its construction and maintenance. Its purpose had been served. Yet if its collapse is to be commemorated not celebrated, its commemoration must be viewed in the context of another commemoration on 9 November – the commemoration of Kristallnacht, of 9 November, 1938, Nazi Germany’s move from legislative restrictions against Jews to the violent beginnings of the Shoah.