Burying the Hatchet in Vietnam

This past week, President Obama visited Vietnam in a move to improve relations with the former adversary. The trip came 40 years after America fought and ultimately lost a long, destructive war in order to stop the spread of communism within Vietnam. The war was devastating for both sides, with about one million Vietnamese communist forces and fifty-eight thousand American soldiers killed, as well as an estimated half a million Vietnamese civilian casualties. The war also wrought havoc on the public health and environment of Vietnam, inflicting wounds that still have yet to fully heal. In the U.S, the war caused deep and rancorous social conflict, to a degree rarely seen through its history, exemplified by the Kent State shootings of 1970.

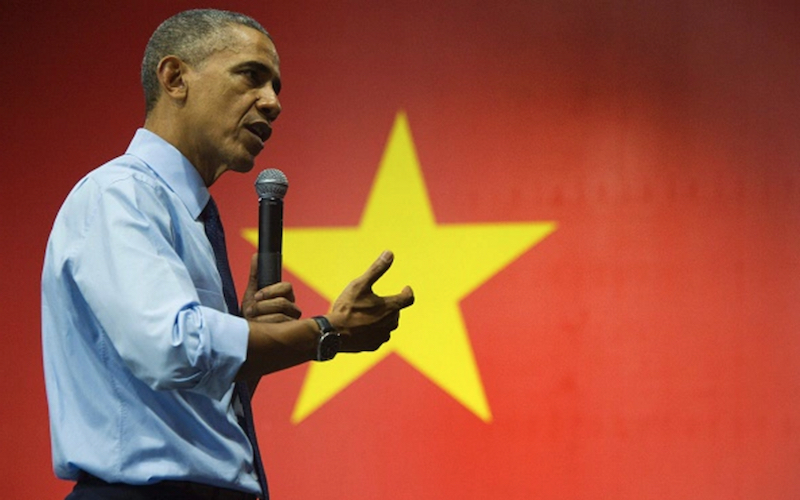

Though the U.S officially ‘normalized’ relations with Hanoi twenty years ago, the trip has seen President Obama announce a full lifting of the arms embargo that had been in place since the official end of the war in 1975. For its part, Vietnam has recently made gestures to loosen the grip on its one party state system, holding a contested election with more candidates than ever before in its history. For both parties, these efforts have been motivated in part by the increasingly aggressive Chinese presence in the South China Sea in Vietnam’s territorial waters – though both the American and Vietnamese governments have for some time shown an increasing desire to move forward.

The environmental and human damage is still raw in Vietnam. During the war, American forces sprayed 12 million gallons of a toxic herbicide called Agent Orange throughout the Vietnamese countryside, to destroy forests that the Vietnamese used as cover from air attacks. The herbicide contained dioxin, one of the most toxic chemicals in existence.

Even though the U.S government pays compensation to American veterans and their families affected by Agent Orange exposure, officials have denied a connection between the chemical and similar health problems experienced by generations of Vietnamese. Debilitating birth defects have mangled populations of Vietnamese born after the war in areas in which Agent Orange was sprayed. Despite official denial, the U.S has increasingly been providing aid to decontamination projects, funding efforts to clean 45,000 cubic meters of soil near Da Nang airbase.

However, the U.S was not the only faction responsible for atrocities during this era of conflict in Vietnam. The 50th anniversary of the Binh An massacre passed last February, commemorated by a memorial ceremony in Vietnam. Over a thousand Vietnamese civilians were killed by South Korean forces in 1966, including 166 children, 231 women, and 88 people over the age of 60. The killings were especially brutal, including sexual violence inflicted on women, and children burned alive by Korean soldiers. Today an entire generation of children of mixed Vietnamese-South Korean ancestry, estimated at 5,000 to 30,000, bear the marks of that tragic decade. Unlike similar massacres such as My Lai on the part of the U.S, there has been no official apology, legal action, or recognition on the part of Korean officials. The task of healing the lasting wounds of the massacre has almost exclusively been left to the civilians of the two countries. South Korean citizens have sent peace delegations, and citizen campaigns such as Voices of Vietnam have recently demanded an official apology from the Korean government and president Park Geun-hye.

Others have campaigned for introducing in California’s textbooks for K-12 students the fate of the Lai Dai Han.

Sadly, the Korean president has stubbornly refused to acknowledge the traumas inflicted on the Vietnamese. When the Vietnamese president visited Korea in 2001, then South Korean President Kim Dae-jung offered an indirect apology, saying “I am sorry about the fact that we took part in an unfortunate war and unintentionally created pain for the people of Vietnam.” Park, leader of the opposition party at the time, released a statement the next day, claiming Kim’s statement of remorse “drove a stake through the honor of South Korea.”

Both the health effects of Agent Orange and the brutality of the massacre in Binh An resonate today, impacting generations of Vietnamese who weren’t even alive during the war. Families were torn apart and much like the dioxin in the soil, trauma from the brutality of American and Korean forces shapes the lives of Vietnamese today. Though these actions cannot be undone, official recognition would go a long way towards helping those affected to find closure. In many cases, the citizens of the countries involved have been proactive and are many steps ahead of their own country’s officials in their efforts to make amends. This should serve as a message to the governments involved that the time has come for full recognition of their actions in Vietnam. Efforts to decontaminate Vietnamese soil and to improve relations will be incomplete without public acknowledgement of the brutality inflicted upon the Vietnamese land and people.