The Saudi Hand in British Foreign Policy

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia always knows when it’s onto a good thing. That particular “thing,” in the few days left before the UK elections, is the May government. That same government that has done so much to make a distinction between policy and values, notably when it comes to dealing with Riyadh.

The United Kingdom has been a firm, even obsequious backer of Saudi Arabia’s war against Yemen. In the traditional spoiling nature of British foreign policy, what is good for the UK wallet can also be good in keeping Middle Eastern politics brutal and divided. The obscurantist despots of the House of Saud have profited, as a result.

The Saudi bribery machine tends to function all hours, a measure of its gratitude and its tenacity. According to the register of financial interests disclosed by the UK Parliament, conservative members of the government received almost £100 thousand pounds in terms of travel expenses, gifts, and consulting fees since the Yemen conflict began.

The Saudi sponsors certainly know which side their bread is buttered on. Those involved in debates on Middle Eastern policy have been the specific targets of such largesse. Tory MP Charlotte Leslie was one, and received a food basket totalling £500.

Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond is another keen target of the Kingdom’s deep pockets, having shown a willingness to defend mass executions in the past. “Let us be clear, first of all,” he insisted after consuming the Kingdom’s gruel on why 47 people were executed in January 2016, “that these people are convicted terrorists.” Four of them, including Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, were political protesters as well, but terrorists come in all shades.

Hammond, instead of going red on the issue, found another Islamic regime of comparable worth to point the finger at. Iran, for instance, “executes far more people than Saudi Arabia.” Best, then, to drop the matter and do such things as accept a watch from the Saudi Arabian ambassador to the value of £1,950.

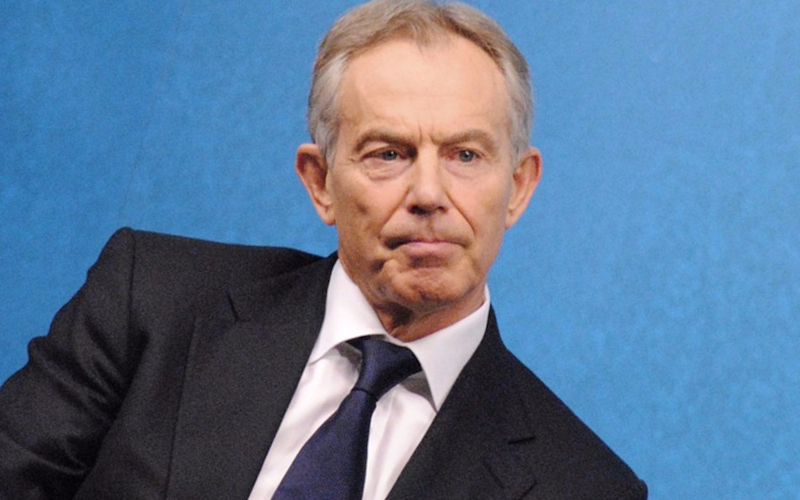

Such a sweetly disposed attitude stands in the annals of the British approach, a matter not so much of sentiment and institution. The Blair government of New Labour fluff was similarly keen to smooth the pathway for the British arms market, while making sure that Riyadh, whatever its policies, was courted.

Attempts to shine a strong, searing spotlight on corrupt practices, notably those linked to BAE, have been scotched, blocked or stalled. One such example, a chilling one given the recent spate of attacks on civilians in the UK, involved a disgruntled Prince Bandar, head of Saudi Arabia’s national security council, threaten Prime Minister Tony Blair with “another 7/7” should a fraud investigation into BAE-Riyadh transactions continue.

High Court documents in February 2008 hearings insisted that the Prince had flown to London in December 2006 to give Blair a personal savaging laced with ominous promise: stop the Serious Fraud Office investigation, or expect London to witness a terrorist inflicted bloodbath.

Blair complied, leaving Robert Wardle, the SFO’s director, stunned. “The idea of discontinuing the investigation went against my every instinct as a prosecutor. I wanted to see where the evidence led.” Not, however, obliging Tony and the happy executioners in Riyadh.

In yet another interesting turn ahead of the June 8 election, Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn has decided to bring the Saudi role behind that policy into full view. Corbyn’s rebranded Labour approach is more hardnosed on the issue of UK arms sales to the Kingdom. Shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry wished for a return (was there every one?) to an “ethical foreign policy,” one fashioned on the approach taken by former Foreign Secretary Robin Cook.

Cook’s ethical thrust, if it could be termed that, came to view in 2003 when he resigned over the Iraq War. “Labour does not accept that political values can be left behind when we check in our passports.”

Not so, according to Blair, whose sense of ethics was always muddled by a contaminating mix of evangelism and fakery. But times are different from Corbyn’s perspective. This is Labour rebooted on Cook’s original objectives: “We will strive,” promised Thornberry, “to reduce not increase global tensions, and give new momentum to talks on non-proliferation and disarmament.”

Thornberry’s words would have sent a true tingling through the Saudi security establishment. In line with the Labour party manifesto, the shadow foreign secretary promised to pursue an independent UN investigation into alleged war crimes in Yemen. Arms sales to the Saudi coalition engaged in that conflict would be suspended.

The picture is not a pretty one when shoved into the electoral process. But then again, the May wobble and turn may well justify such a relationship on terms that Saudi security and power is preferable to other authoritarian regimes. These big bad Sunnis are the good Muslims of the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

Such splitting of hairs doesn’t tend to fly well from the stump and the Tories might well attempt to keep things as quiet as possible. The Saudis, on the other hand, will be wishing for business as usual, praying that the threat of a Corbyn government passes into the shadows of back slapping Realpolitik.