Is ‘The Nightmare Before Christmas’ the Reason Why My Favorite Band Broke Up?

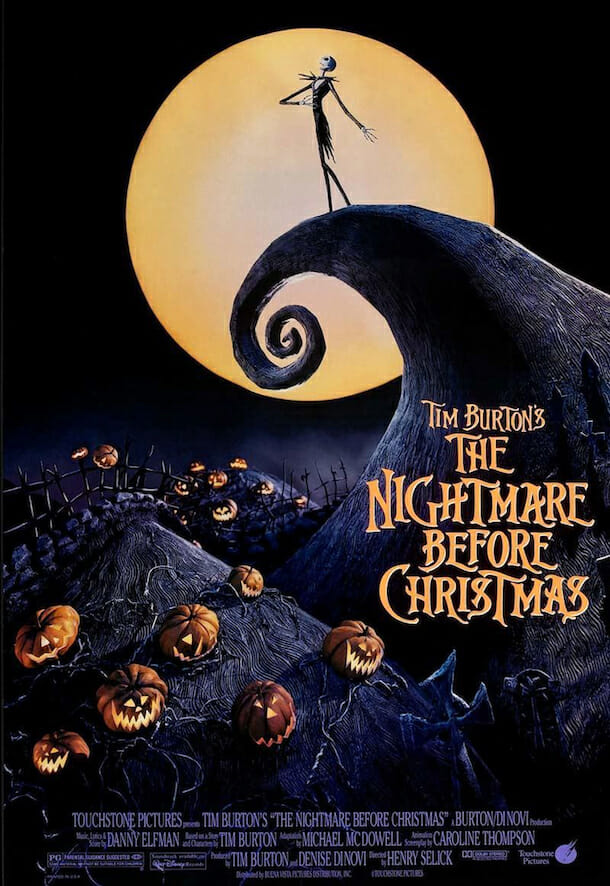

October 27, 2018. Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles, California. Film composer Danny Elfman, guitar in hand, comes out for an encore after a live performance celebrating the 25th anniversary of the classic holiday-themed stop-motion animated movie, 1993’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. Elfman composed all of the film’s music and had done these sorts of performances of it annually around Halloween in previous years. 2018’s show included a worldwide, renowned ensemble of musicians, a full orchestra, and guest appearances by the likes of Paul Reubens (best known as Pee-Wee Herman) and living legend Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek, Home Alone, SCTV, Christopher Guest movies and so much more).

Elfman addresses the audience. “Thank you. 25 years. I’m not allowed to say what I want to say, so: who would ever FREAKIN’ believe this?” he asks the audience in astonishment. He introduces his band and concludes with “and on my right, a man who stood on my right for seventeen years with Oingo Boingo…” The audience cheers at the invocation of the band’s very name. The man is Elfman’s longtime collaborator and former bandmate, Steve Bartek. Together, Elfman, Bartek, and the orchestra perform one of Oingo Boingo’s best-known songs, “Dead Man’s Party,” the title track to what is easily the band’s best album.

It was one of only a handful of times Elfman had performed the song publicly since the breakup of the Oingo Boingo in 1995, the performance of the song itself seemingly only coming into existence because of an event commemorating The Nightmare Before Christmas, of all things. Elfman, losing some of his fiery-red hair, now sports glasses and wears a demure black t-shirt instead of his once-usual tanktop. He fills his performance with big gestures and a cocky head-roll, invoking his stage style from when the band was its height. It’s the same manic energy he displayed in the Rodney Dangerfield comedy vehicle, 1986’s hilarious Back to School, worth revisiting if only for the supporting roles by the likes of a very young Robert Downey, Jr., Karate Kid/Cobra Kai’s William Zabka, and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’s Terry Farrell. In the film, Dangerfield hires the band to play the song during what the movie wants us to believe is the coolest college party in history, so cool it even disrupts the plans of the Zabka’s frat-boy antagonist. This was Oingo Boingo during its imperial phase in the mid-to-late-80s, where they, alongside bands like DEVO, Depeche Mode, and the Talking Heads, were an alternative, new wave, irreverent yet thematic, synch-inspired subgenre led by prolific and talented frontmen that revolutionized music.

I used to think of this moment, watched and re-watched countless times on YouTube over the past 2 years, as merely an impressive performance of a favorite song, unexpectedly emerging fairly recently and from a mostly-unrelated concert. Now, I view it as embodying the curious intersection between the respective stories of Oingo Boingo and Nightmare Before Christmas, and how eventually, one began to eclipse the other in a moment of transition that is reflected in both the film’s music and main character’s motivation.

If you couldn’t tell, Oingo Boingo is my favorite band. I first stumbled onto them through that very song, “Dead Man’s Party”. I was a teenager, wanting to make a Halloween-music playlist, and iTunes recommended a song I had never heard of. It became easily my favorite song that I had discovered in a long time, I loved the title track so much and I was curious enough that I bought the entire album. The 1985 album Dead Man’s Party is easily one of the best albums of the 1980s. It demonstrates that Oingo Boingo had come into its own musically, overcoming an initial irreverence inspired by punk to instead evolve into something that felt very of the moment, a mesh of 80s synch and new wave sound. And that was before you get to Elfman’s personal contributions: he wrote all the songs on the album, and his own personal obsessions with themes of death and its related imagery, mortality, spirituality, and existentialist philosophy bleed through it. The album even features songs that defy categorization, such as the surprisingly-heartfelt ballad “Stay,” which for some reason became so hugely popular in Brazil that a compilation of the same name was released to popularize the song’s success; or their the band’s theme song to the John Hughes teen comedy Weird Science, the music video for which Elfman admits he’s embarrassed by and was famously mocked by Beavis and Butt-Head. In that episode, Butt-Head says of Danny Elfman “this guy thinks he’s, like, smart,” and of Oingo Boingo’s music: “I think it’s only cool if you [went] to college.”

Soon, I had to buy the band’s whole back catalog and proceeded to get really into their music. Part of what interests me about the band is that they appealed to the base lizard-brain of my teenage self, but yet their music still deeply resonates with me now, a decade past my teen years. Part of it was that the band’s M.O. seemed to be irreverence, not anarchic but rather thoughtful, as evidenced by the band’s roots in both punk and comedy. The band formed out of what Wikipedia describes as a “surrealist street theatre troupe” called the Mystic Knights of the Oingo Boingo, initially founded by Danny Elfman’s older brother Richard. After Richard left the group, Danny’s pivot to music allowed further experimentation, but he never forgot those surreal or performative roots, and that proceeded to bleed into the lyrics. The band’s first album, Only a Lad, was released in 1981 and was received with controversy. I think of the album as representing the band at their most intentionally outrageous, channeling punk energy fragrantly but without much nuance, though both the album’s title track and the song “Capitalism” feel as pertinent today as when they were released.

Their next two albums, 1982’s Nothing to Fear and 1983’s Good for Your Soul, overcame that initial stumbling block to craft the sort of music that would become the band’s mainstay: a mix of synth sound, popping rock energy, a hint of ska, experimental ballads, and sardonic humor. In 1984, the band briefly sojourned away from being credited as such, supposedly in order to support Elfman’s attempt to go solo in an album called, of all things, So-Lo. That album was credited solely to Elfman despite having much of the same lineup as the previous albums, the reason why allegedly being because of a contract dispute between record labels. That was abandoned and the band returned to simply being Oingo Boingo, and opened for The Police on several occasions during many of their tours, including the Synchronicity tour. The next two albums, the previously mentioned Dead Man’s Party in 1985, as well as 1987’s Boi-Ngo, were a creative high-point for the band, combining Elfman’s compositions with inventive, innovative new sound. The band doubled down more on ballads on 1990’s Dark at the End of the Tunnel, predicting a decade that would see the rise of such power-ballad singers as Michael Bolton and Seal.

Then, in 1994, after Danny Elfman had concluded his work on The Nightmare Before Christmas, among other movies, and after a four-year-long gap between albums, the band rebranded themselves merely as Boingo. They also released an album of the same name, which was received as a disappointment. Things that had become deeply associated with the band, such as a horn section, were abandoned in Boingo. The band’s story came to an end shortly thereafter, on Halloween 1995, when they played one final show at the Hollywood Amphitheater, filming it for a package video and album release entitled Farewell. After that, Oingo Boingo was no more, with the rumor of a reunion tour frequently being squashed by Elfman himself, citing permanent hearing damage from their concerts in the 80s making him reluctant to tour again.

Meanwhile, an entire generation, myself included, has grown up with the band’s output being this now-concluded thing. The people I have met who are similarly into the band comprise a diverse, but a mostly-cultured lot. Any reference to the band in pop culture were so few and far between that they really resonated, from that time on Community where Jeff (Joel McHale) speculated that Britta’s (Gillian Jacobs) conception happened because “her mom gets freaky when she hears Oingo Boingo,” to a montage in the season premiere of Stranger Things season 2 set to a personal favorite, “Just Another Day,” that had me cheering so loud I think I legitimately startled my housemates at the time. Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One begins with the novel’s Willy Wonka-equivalent, James Halliday, announcing his death to the world by starring in a personalized music video for “Dead Man’s Party,” immediately endearing it to me forever. (And when that scene wasn’t included in the film adaptation, it served as a major strike against it.)

When Elfman began performing this beloved Oingo Boingo song in public during these Nightmare Before Christmas concerts, it excited the faithful, myself included, as him wanting to dip his toes in the water before possibly committing to some kind of musical reunion. So imagine my surprise when, upon watching the episode of Netflix’s The Holiday Movies That Made Us about the making of The Nightmare Before Christmas, Elfman revealed to the camera that “[Nightmare Before Christmas protagonist] Jack [Skellington] was an extension of how I was feeling at the time.”

“A lead singer in a band is like a king of their own little world, but I was at the point where I didn’t want to be in a band anymore,” he admits. “I was writing from my own heart: [Jack’s] got all these fans, and people love him, but he’s not happy.” The show then plays a segment of a song Jack sings at one point, synched up with footage of Elfman performing with Oingo Boingo in front of an adoring crowd: “Year after year/It’s the same routine/And I grow so weary/Of the sound of screams…” The implication couldn’t be more obvious: Danny Elfman credits the process of working on the film for motivating him to want to leave the band.

Watching the show made me want to revisit The Nightmare Before Christmas, which I did the other night. It surprised me how much it held up and how engaged with it I was, there were still moments that made me laugh despite the countless times I’ve seen it. I surprised myself by singing along to many of the songs. It’s such a strange vision of a film, Christmas by way of the Addams family. Though Tim Burton didn’t direct, his name was all over the marketing (the opening title still names the movie as Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas), and it’s also clear that his distinct gothic fingerprint is apparent throughout. Credit must also be paid to director Henry Selick, who used the experience he gained on this film in later productions such as James and the Giant Peach (1996) and Coraline (2009). As someone who is well-documented as loving to celebrating Halloween, the film serves as a fun synthesis of the aesthetics of the two respective holidays, the slimy spookiness of All Hallow’s Eve meets the wintery purity and evergreen color of Christmas. The music is impeccable, obviously. I’m additionally impressed by the performances of Catherine O’Hara as tortured ragdoll girl Sally, Chris Sarandon as Jack’s speaking voice, and Elfman as his singing voice. (Sarandon was cast due to his voice’s resemblance to Elfman’s.) There’s an ensemble of wonderful characters, I like Sally’s creator, the strange Dr. Finklestein (William Hickey); the manic two-faced Mayor of Halloween Town (Glenn Shadix); and Lock (Paul Reubens), Shock (O’Hara), and Barrel (Elfman), three deviant trick-or-treaters who sing what may be the film’s catchiest song, “Kidnap the Sandy Claws,” where they plot and scheme to steal Santa away from Christmas Town. They work for Oogie Boogie (Ken Page), who is holding Santa Claus himself (Ed Ivory) so that Jack can take over Christmas present-delivery duties, threatening to ruin the holiday in a spectacular fashion.

But now, knowing what I do about the film’s connection to Danny Elfman’s thought process concerning Oingo Boingo, the song “Jack’s Lament,” which was sampled in the show, definitely captures someone struggling with their own creativity and talent, as well as feeling restless. “There are few who’d deny, at what I do I am the best/For my talents are renowned far and wide,” Jack sings, boasting with rock-star swagger. However, Jack sounds legitimately sad when he later sings “Oh, somewhere deep inside of these bones/An emptiness began to grow…A longing that I’ve never known.” When describing his role as the Pumpkin King of Halloween Town, he says that he “would tire of his crown, if they only understood/He’d give it all up if he only could.” Could the “they” he sings of possibly be his legion of Oingo Boingo fans? Jack concludes by singing “The fame and praise come year after year/Does nothing for these empty tears…”

I was moved by Elfman articulating his struggles into the song, which were much more noticeable now that I knew to look for them. The whole film feels like it’s about someone being pulled by two different worlds, in a moment of great transition. The song immediately following “Jack’s Lament” is called “What’s This?” which Jack sings upon stumbling into Christmas Town. The song captures the joy of discovering something new, and the enthusiasm of finding something that feels refreshing and exciting. Maybe that song encapsulates the process of Elfman crafting the film’s music itself, unbridled exhilaration at finding something that felt more creatively fulfilling. In my life, I too have felt that. How fitting that Jack, like Elfman, previously identified with being a Halloween rebel (Oingo Boingo was famous for their Halloween-night concerts back in the day), but opts for the family-friendliness and seasonal magic of Christmas. To a certain extent, Nightmare Before Christmas is a story about maturation, gaining a new, well-rounded outlook, and that seems to reflect what Elfman was going through during the film’s development.

But, being the Oingo Boingo-enthusiast I am, I know that the story isn’t really that simple. By the point The Nightmare Before Christmas rolled around, Elfman had already written the scores to blockbusters like Beetlejuice and Tim Burton’s two massively popular Batman movies; another holiday classic, Scrooged; and many others, as well as composed the theme song for The Simpsons. (In another Oingo Boingo connection, Elfman had met Simpsons creator Matt Groening because he had given one of the band’s concerts a bad review.) The writing was pretty much on the wall that’s where his future endeavors were focused, and as the band’s creative head and emotional center, he simply couldn’t have it both ways. Also, the band’s failed rebranding merely as “Boingo” and the mixed-to-negative reception to their album of the same name likely contributed to their downfall. The band infamously wore skater clothes while promoting the album, only contributing to an image of a band simply not cut out for the 1990s. All this and more was likely weighing on Elfman at the time.

But, the revelation of the impact the production of Nightmare Before Christmas in particular had on Elfman’s way of thinking was a new piece of information I had not previously been privy to. I had chalked up the closeness of the release of the film and Oingo Boingo’s breakup as mere coincidence, or an example of how much Elfman’s film work was accelerating that the band ceasing to continue felt like an inevitability. But now, I am left to ponder whether or not one of my favorite movies from childhood and a Christmas-time classic is the Yoko Ono of my own respective favorite band.

My personal favorite Oingo Boingo songs for curious new listeners: “Dead Man’s Party”; “Just Another Day”; “Stay”; “Elevator Man”; “Pain”; “My Life”; “Only a Lad”; “Capitalism”; “Private Life”; “Wild Sex (in the Working Class)”; “Who Do You Want to Be?”; “Ain’t This the Life?”; “Good For Your Soul”; “Nothing Bad Ever Happens”; and, “Goodbye, Goodbye”