Ghosts of Tuol Sleng: Memory and Murder in Phnom Penh

It was a bad sign. Not an omen or a portent of misfortune—just a bad sign. It bore the name of the place I was looking for but stood at the wrong location. Beside it, at a dusty crossroads, a shop and restaurant sat side by side. The proprietor, well-accustomed to weary travelers, pointed without prompting, gesturing 200 yards down the road toward my destination: the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum—known more simply as Tuol Sleng.

At the entrance kiosk, a $10 fee secures both admission and an audio guide. Not to explain—explanation seems too neat for what happened here—but to present, to lay bare, the history of a former high school in Phnom Penh turned slaughterhouse. On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge seized power. Between 12,000 and 20,000 people were detained within these walls; of them, only 7, 12, or 14 survived, depending on the source. In 1979, the Vietnamese ousted the Khmer Rouge from power—yet shamefully, the United States and the United Kingdom continued to recognize this murderous organization as Cambodia’s legitimate government, clinging to Cold War Realpolitik deep into Bill Clinton’s first term. Decency, it seems, had been jettisoned long before Donald Trump.

Under the Khmer Rouge, nearly 2 million Cambodians perished—slaughtered, starved, or lost to disease—in a country of just over 8 million. Modernity was outlawed under Pol Pot’s decree of “Year Zero.” Even something as innocuous as a pair of reading glasses could mark someone—child or adult—as an intellectual, and therefore an enemy of the state. Literacy became a mortal danger.

Upon entering the compound, one encounters 14 white-painted slabs. When the Khmer Rouge abandoned Tuol Sleng—also known as S-21—only 14 prisoners remained. They were executed just before the regime’s flight. Their remains now lie beneath those slabs, stark memorials discovered by Vietnamese soldiers.

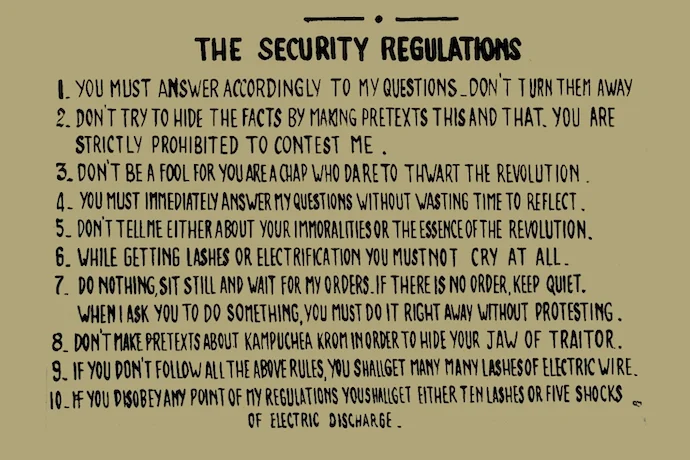

Nearby, a sign issues the chilling regulations prisoners were expected to obey.

Yet, improbably, the grounds offer flashes of natural beauty. Jacaranda trees and coconut palms, survivors from the Khmer Rouge era, dot the central garden. Their blooms and fronds seem almost indecent in a place so heavy with sorrow.

The former classrooms, converted into cells, housed as many as 1,500 prisoners at a time. Tuol Sleng was not a death camp in the conventional sense; arrival here didn’t necessarily mean immediate execution. Instead, prisoners were systematically tortured to extract confessions—true or false—before being transported to one of Cambodia’s infamous killing fields.

Photographs of the prisoners line the walls, their eyes staring out: terrified, pleading, resigned. It’s almost unbearable. Yet bearing witness—especially to atrocities committed by the victims themselves—is necessary.

Roughly 80 percent of those imprisoned at Tuol Sleng were Khmer Rouge cadres, purged by a regime that, like all revolutions eventually do, turned on its own.

The seeds of this horror were fertilized by American bombs. In a secretive and illegal campaign meant to sever Vietnamese supply lines, the U.S. dropped nearly 2.8 million bombs on Cambodia by August 1973—raining destruction on a largely agrarian society. Out of that devastation, the Khmer Rouge swelled with recruits.

Today, 50 years after the Khmer Rouge rose to power, a shopkeeper selling soda and canned goods still stands at the crossroads, pointing visitors toward a former school—a quiet yet searing reminder of humanity’s capacity for cruelty.