Resiliency and Healing in Cambodia

In December 2016, along with 24 graduate students of George Mason University, I went to Cambodia for two weeks. I was excited and ready to experience Cambodian culture, especially their spirituality practices. I decided to be mindful and accept the unfamiliarity of a new environment, culture and its people. I was inevitably ready to learn firsthand about the genocide and its aftermath whilst listening closely to the personal accounts of the victims and witnesses of the massacre. I hoped to see signs of development in the cities and hoped to feel a sense of peace, forgiveness and trauma healing among the Cambodians. I was open to make new friends and make my encounters memorable. I intended to look for signs of development and civilizations, learn from the professionals I met along the way, and to not judge.

Despite many negative signs and stories of the bloody history of Cambodia, my travel experience was boosted and enriched with love, compassion and valuable stories. I learned about the beautiful culture of Cambodia and I learned more about myself. I encountered a number of professionals and sincere monks at Siem Reap, Battambang and Phnom Penh who helped me think about how I can better be at service of others.

One bloody chapter of Cambodia’s history has cast its present and foreseeable future into a state with many challenges. What happened to Cambodia between 1975-1979 was neither caused by a natural disaster, nor due to human error, but instead purposefully done by humans against humans. The Pol Pot regime has left a deep wound in every single Cambodian’s heart who experienced the viciousness of the Khmer Rouge period. Victims and perpetrators all suffered from the genocide’s consequences. The genocide has damaged not only those who directly experienced the inhuman act, but also the generations that followed. The aftermath of the genocide left a wide spread psychological malaise among Cambodians, which hinders the development of Cambodia as a whole. The information I gathered from the intellectuals, experts in Cambodia’s history, and the tour guides’ of sites I visited all indicate that Pol Pot was flattening the life style of Cambodians by destroying entirely advanced life necessities such as radios, watches, clocks, lamps, etc. Not only did the regime destroy life necessities and communication devices, it also went after intellectuals, doctors, technicians, teacher, students, and people wearing glasses. They specifically targeted anyone who showed signs of wealth with soft hands, along with people with fair skin/foreigners. Factories, banks, hospitals, universities and schools were shut down. Those who were lucky or privileged enough to escape Pol Pot’s execution either did so by hiding or creating aliases, living in disguise.

During the Khmer Rouge era, family life was devastated. The attack on traditional familial values was a serious destruction issue of Cambodian culture. Children were seen as vulnerable and easy targets to brainwash. After Pol Pot, the entire infrastructure was affected; it was very challenging to rebuild the country’s distorted economy, health and education. Pol Pot converted the country into an agricultural society with no connection with the outside world (according to Tuol Sleng tour guide). The horrific genocide has affected the current infrastructure in Cambodia. Schools, hospitals, roads and utilities are open now, yet most are in very poor condition. The educational system in Cambodia, particularly from my insights in Siem Reap seemed to be worrying. Instead of participating in school during the day, I witnessed kids working in stores, or playing outside. Their clothes were both old and torn. I noticed piles of garbage in the street, creating perfect hosts for the bugs and roaches that swarmed the cities. Main roads were mostly busy and traffic was congested most of the time. There was no sign of zoning laws and or effective law enforcement.

Could a psychologically traumatized nation heal, move forward and develop the country?

Victims of war and oppression experience trauma. It is extremely hurtful for people who are forced out of their homes. I know the feeling, twice my family and I were forced by Saddam Hussain’s regime to leave everything behind and move out of our city. It is the worst feeling when your freedom is taken away from you, to be powerless, and your human rights are violated in entirety. Evacuation events cause disorder. Trauma hinders victim’s ability to cope, have control, or find meaning for the negative experience. Those who lived through and survived the Khmer Rouge era, the displacement and violation experience have been left with depression and insecurity for the future. Now, they are home but the traumatic events may still haunt many of them.

Untreated trauma has a long-term crippling effect on its victims. The entire nation has been traumatized. Majority if not all need family and friends’ help and support to overcome post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Can victims help another victim heal? I believe the answer is yes. Some victims are stronger emotionally and psychologically than some others, also, it depends on the level and severity of the trauma. Additionally, I think some victims are resilient and capable of transforming their dark experience into empowerment; they then become experts who want to use their experience to help others heal.

Broken people are still living in a broken society. Because of the variety of crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge, healing and reconciliation may seem to be elusive for some victims. The Cambodians either were perpetrators during the Khmer Rouge or they were victims. What did they witness and why did it happen? What they witnessed are now their stories and why it happened, most people still cannot come up with justified explanations. If you ask anyone who knows right from wrong, what needs to be done, the answer is to get justice for the victims, and therefore the perpetrators must be punished.

The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) is the first special court in the world established to try the most senior members of the Khmer Rouge responsible for heinous crimes. The court formed in June 2003 but officially began working in January 2006 with a hybrid tribunal that includes four Cambodian and three United Nation judges on the bench negotiating the future of the people who were responsible for planning and leading the genocide horror to be held accountable for their crimes. After 10 years, lengthy complex trials and 280 million dollars later, only two people have been punished. It is really questionable to continue wasting time, energy and money going after perpetrators who are now in their nineties. Memories have faded and most likely even if they are sentenced; they may soon die in prison. On the one hand, it is important to give Cambodians explanation and closure with a way to understand what happened in their country, on the other hand, the ECCC “pyramidal type” structure may have created a sense of panic in Cambodian society and led to renewed trauma and tensions among the victims. I do not know how fair and transparent the proceedings were, but if the court structure is “essentially a top-down,” as it is stated by Greg Stanton, professor and expert in genocide studies and prevention at George Mason University’s School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution (Campbell, 2014), it is unjust and wrong to only focus on one group within the Khmer Rouge. What about the actual killers? The ones who slaughtered and tortured adults and starved children to death? The extensive nature of the crimes requires that more than five old men be held accountable. The fund that is donated by 30 donors to finance ECCC can be assigned for community developmental and educational projects. For the victims who need to obtain trauma healing and willing to forgive their perpetrators, the Cambodians have another category that is involved in achieving forgiveness. It is their belief, spirituality or Buddhism, not through the court system.

Cambodians appeal to elements of Buddhism in their efforts to calm their minds. Over the last 20 years Buddhism has progressively resurfaced and many Cambodians pin their hopes of coping with their bloody past and restoring “moral order” in the future on Buddhism. While meditation may help reduce distress, Buddhism also recognizes that suffering (dukkha) is an essential piece of the human condition. As Mr. Natha Dannothadharm explained, because all people are born with suffering, the objective of meditation is therefore not to end suffering but to transcend it.

Since Cambodia’s past has severely affected many people, communal rituals take place in symbolic places for spiritual power to manage to heal and reestablish moral order. By meditating and participating in the various memorial events and ceremonies, victims and perpetrators can engage with traumatic remembrance glorifying the people they lost to the Khmer Rouge. They form communal memory and make sense of tragedy within the framework of a general process of social recovery. Honoring each other’s hurt and stories, proves that the mediation process is a successful method of trauma healing.

I have no doubt that some of the victims who are still suffering from psychological trauma will soon recover and begin to live their peaceful lives once again. For some survivors like Ms. Oddom Van Syvorn (peace activist and meditation teacher) and victims of landmines who lost their arms or legs in the most spiteful civil war, I am not sure how long they will take to heal, or will they ever begin living trouble-free lives.

Survivors need to be heard. Some survivor’s stories have never been told. I think trauma healing in all levels is a social process; it does not happen in isolation. Families and individuals who have experienced traumatic situations need to heal psychologically and emotionally. To enter the healing process, the victim must first acknowledge the effects of the trauma and be willing to accept their family and social support. In other words, to deal with the past and to move forward, the community must make a conscious decision about healing and acknowledge that trauma needs healing.

In “Healing from War Trauma through Nature,” Stephanie Westlund indicates that some veterans with war trauma are turning to farming and animals to recover and reintegrate themselves into civilian life. Does it mean that the majority of Cambodian farmers who are around nature are now actively healing each and every day? I do not know the answer to that question, as I did not get a chance to meet farmers from the villages or cities who were affected by the genocide. However, I have seen and learned from some great monks at the Buddhism for Education Center (they grow daily produces, fruits and vegetables) that not only do they have direct and easy access to healthy foods, but also caring for their small farm is therapeutic and helping them to stay focused, happy and resilient.

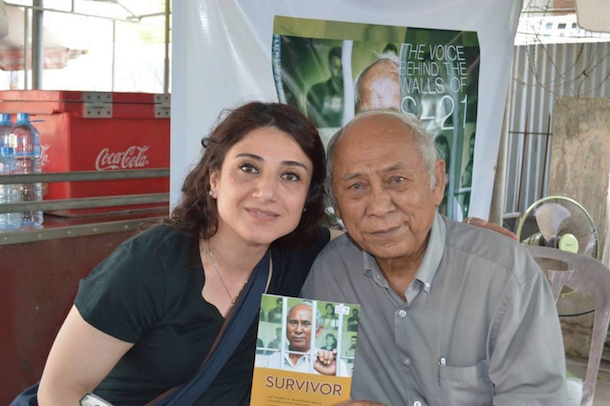

People handle trauma in different ways. Even though victims may experience similar types of abuse, the response to trauma may vary from person to person. Meeting some Cambodian survivors particularly two of the ones who have been through serious traumatic torture in Tuol Sleng (S-21 interrogation and torture center) was a peculiar experience. Mr. Bou Meng, a survivor of office S-21 is a former prisoner and painter. Through a series of paintings and publishing a book he shared his painful story including a revelation of losing his wife in 1977 in a killing field. He survived, but as he describes it in his book Bou Meng: A Survivor from Khmer Rouge Prison S-21 the ghosts of those who died still follows him. It is incredibly amazing that he is still alive and continues to share his story many times every day with many tourists, researchers and others who are curious about the stories of S-21. Many Cambodians did not have Mr. Meng’s luck, his life was saved because he painted portraits of Pol Pot. Meanwhile, Mr. Chum Mey who was separated from his wife and four children, after an intensive interrogation and torture including breaking his little finger and pulling out his toe nails, his life was saved because he confessed and began sharing information that the regime wanted to know.

The Cambodians are one of the most resilient people I have ever encountered. Unfortunately, not all victims or survivors of Khmer Rouge regime were able to share their stories through paintings, books or publications. Some stories stay untold and some wounds stay unhealed. Sometimes, people who investigate crimes may be able to put pieces of the victims’ lives together and tell their stories by testing their bones, teeth or clothing.

I still struggle with understanding the current Kingdom’s governmental priorities, policies, and implementation. My understanding is that a vast majority of the Cambodians are Buddhist, or spiritual. They believe in love, kindness and compassion even for their enemies. What do the key decision makers believe? Who do they pray to? Why can the Cambodian people love even their enemies, but the kingdom and the decision makers cannot love their own people? Incredible temples with puzzling structure, palaces full of silver, gold and valuables, and huge trees with multiple veins and visible roots are all indications of Cambodia’s rich heritage. That memorable heritage made me happy to know hundreds of years ago people in Cambodia passionately built them and protected them even throughout the genocide. In contrast, I was very sad to see statues worth billions of dollars covered in silver and gold while there are no serious attempts for improving education, healthcare, and governmental structures to lift people out of impoverished circumstances. I cannot hold anyone accountable for the poverty, illness, illiteracy, and poor conditions of the cities in Cambodia but the corrupt government.

Representation of Cambodians

The metaphor that best describes my entire travel experience is the giant trees by the Ta Prohm temples at Angkor. Huge trees, substantial ancient redwoods and oaks are combined into the walls, and rocks hugging the giant roots give the temple a surreal look. The entire temple is covered by overgrown trees. To me, those unique and still standing old trees from the late 12th century characterize the entire life of the country and its people. The interwoven roots with the magical effect represent the family and the community bond before the Khmer Rouge. The thick bodies of the trees symbolize the age of the country and its heritage. The green leaves on the top of the trees with the new growth represent hope, resilience, healing and the future. Despite the evil genocide, the people are still standing and cherish their humble lives. The entire country is in the rebuilding, rehabilitation and developmental process.