Šukrija Meholjic on the Legacy of the Srebrenica Genocide

Šukrija Meholjić is a Bosniak survivor of the Srebrenica genocide who fled in 1992, eventually resettling in Norway. A self-taught artist and published author, he began drawing caricatures in a refugee camp in 1993 as a way to process the trauma of war and displacement.

Over the past three decades, Meholjić has created hundreds of illustrations and authored three bilingual books in Bosnian and English, with his work exhibited internationally. Through both his art and writing, he commemorates the victims of genocide, confronts denialism, and grapples with the nationalist forces that continue to threaten Bosnia’s fragile unity. His work is at once deeply personal and profoundly political—a therapeutic act of memory and a public plea for vigilance.

In this conversation, Meholjić reflects on the haunted legacy of Srebrenica, describing it as a “city of ghosts,” scarred by irrevocable demographic loss and the enduring shame of global indifference. He speaks of the moral imperative to remember—through education, memorials, and official recognition—and warns of the dangers posed by ongoing denial and secessionist rhetoric. His testimony, like his art, is a form of resistance—a personal reckoning and a collective call to never forget.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: What is the legacy of the Srebrenica genocide?

Šukrija Meholjić: That is complicated. After the genocide, Srebrenica became a city of ghosts. Only a small percentage of the original population remained. The majority were killed or displaced during the genocide in July 1995.

However, the persecution and killings of Bosniaks in eastern Bosnia had begun much earlier, during the war that started in 1992. Between 1992 and 1995, thousands of Bosniak civilians were killed in towns and villages across the region, including in areas like Bijeljina, Zvornik, and Vlasenica.

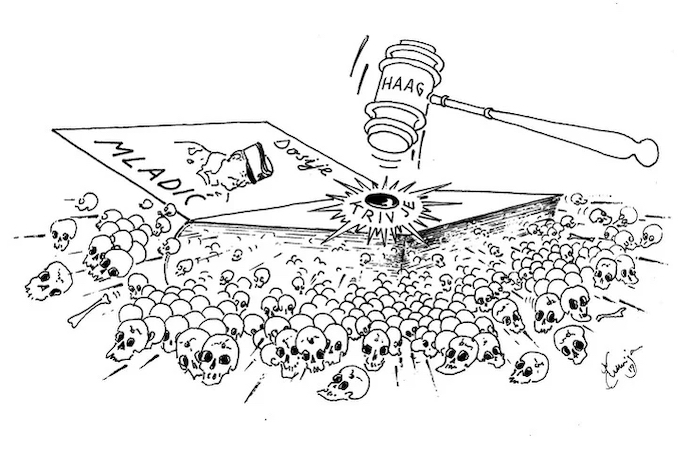

The genocide in Srebrenica in July 1995 marked the most brutal and concentrated episode of mass killing. Over 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were systematically executed by units of the Bosnian Serb Army of Republika Srpska under the command of General Ratko Mladić. It was the worst atrocity in Europe since World War II and has been legally classified as genocide by both the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Court of Justice.

Some older survivors did return to Srebrenica after the war, but the town had changed irreversibly. It became a place of silence and sorrow, with more dead commemorated than living remembered. The demographic destruction and post-war neglect contributed to ongoing depopulation.

Life after the war has been brutal. Today, young people who return to the area face high unemployment, inadequate healthcare, limited educational opportunities, and a lack of cultural and economic infrastructure. As a result, many continue to leave Srebrenica.

Srebrenica is no longer what it once was—and it is unlikely to regain its former vitality any time soon. That is all I can say for now. I am unsure whether I will continue discussing this issue or move on to something else.

Jacobsen: How did this evolve for you?

Meholjić: I am one of the original residents of Srebrenica who had to leave in the early stages of the Bosnian War back in 1992 before the siege of Srebrenica began. Two days before severe fighting reached the town, I evacuated with my family in an attempt to save them. Eventually, it became clear that returning was impossible as the war escalated.

We first went to Croatia, where we lived for a year, and then relocated to Norway, where we still reside. Every summer, we return to Bosnia and Herzegovina—especially to Srebrenica.

During those visits, we usually go to honour the victims. It is a painful and challenging experience not to see my friends, neighbours, and those I lived with for so many years. Instead of shaking their hands, I now visit the Memorial Center in Potočari to pay respects to their remains.

This is the reality that life has imposed, but we must continue forward. We must never forget Srebrenica—for the sake of those who were killed, for those of us who survived, and for the generations yet to come.

We must remember Srebrenica because it represents the deepest wound in the history of Bosnia. It is the tear on Bosnia’s face. Moreover, it is essential to recognize that the genocide in Srebrenica was not an isolated act. Mass killings and ethnic cleansing of Bosniak civilians took place in other parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina as well—such as in Prijedor, Foča, Višegrad, and elsewhere.

We must remember Srebrenica in every possible way to prevent such crimes from ever happening again—anywhere in the world.

I will not remain silent, but I will not destroy myself through my illustrations and caricatures, which I began creating in a refugee camp in Norway. I drew my first caricature shortly after arriving in Norway in 1993. From then on, I continued drawing them, one after another.

In a way, it became a personal therapy—an outlet to release the emotional burden I carried, filled with questions: Why? Why did all of this happen? Why did my neighbour—someone I had sat with and shared food and drink with—suddenly take up a gun and shoot at my friends and me?

It was initially incomprehensible to me. However, the political agenda behind it became clear. The leadership in Serbia, under Slobodan Milošević, sought to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina into two parts—collaborating with Croatian President Franjo Tuđman. Their goal was to eliminate Bosnia and create a “Greater Serbia” and a “Greater Croatia.”

That plan, however, never fully succeeded. Although the international community imposed an arms embargo on all of the former Yugoslavia in September 1991, the former Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) and its vast arsenal were essentially handed over to Serbian leadership. This gave the Serb forces a significant military advantage.

Meanwhile, in 1993, the Croatian Defence Council, with support from the Croatian Army, began attacking Bosniaks in parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina—furthering the joint goals of Tuđman and Milošević.

In response, the Bosniaks—along with all patriots of Bosnia and Herzegovina—united to form a comprehensive defence force. This led to the creation of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which mounted effective resistance against both Serb and Croat forces.

At one point, this army advanced close to Banja Luka, a key stronghold in the region. When it seemed that the liberation of Banja Luka was near, Milošević appealed to U.S. President Bill Clinton and diplomat Richard Holbrooke, who was leading peace negotiations, to stop the Bosnian forces and initiate peace talks to end the war.

Tragically, that request was granted. The war was halted, and the Dayton Peace Agreement was signed. In retrospect, had the offensive continued, Bosnia and Herzegovina might have been preserved as a unified, sovereign state—without the internal divisions that persist to this day. Thirty years later, the successors of Milošević’s ultranationalist policies still deny the genocide and continue to push for separatism.

Today, leaders of Republika Srpska—one of the two constituent entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina—are attempting to secede. Though Republika Srpska has no legal right to unilateral independence, its leaders, with the backing of Serbia, continue attempts to divide the country and destabilize its sovereignty.

Jacobsen: What did the international community do well?

Meholjić: First of all, what did they fail to do correctly? The United Nations had its representatives in the so-called protected area of Srebrenica–Žepa. This zone was established in 1993, not 1995.

There were United Nations peacekeeping troops stationed there, mandated to protect the civilian population. However, when the Bosnian Serb Army, under the command of Ratko Mladić, attacked the Srebrenica enclave in July 1995 and carried out genocide against the population—not only in the municipality of Srebrenica but also in surrounding areas—the UN troops did not intervene. They did not prevent or stop what the Bosnian Serb soldiers were doing to the civilians.

Srebrenica was left entirely alone in the world. The international community, particularly the United Nations, failed to take action. They stood by and did nothing. Moreover, that failure will remain a moral burden for the rest of their lives.

We will never forgive the United Nations representatives for that failure. Because had they truly wanted to protect Srebrenica, not a single life should have been lost during the genocide of 1995. Unfortunately, it took until very recently for the UN General Assembly to adopt a resolution officially designating July 11 as the International Day of Remembrance of the Srebrenica Genocide.

That is a significant step. We thank them for that because now no one will be able to say, “I did not know about Srebrenica,” or “I did not hear that a genocide happened there,” or “I did not know who the perpetrators were,” or “I did not know who the victims were.” The resolution makes it clear: July 11 will be marked internationally as a day of remembrance for the genocide when close to 8,000 Bosniak men and boys from Srebrenica were systematically murdered.

That is a significant achievement. From now on, this day will be commemorated worldwide. It will not be forgotten. It will become part of school curricula, institutional memory, and educational programmes. It will shape how future generations understand and remember this tragedy.

Moreover, it will serve as a starting point to prevent similar genocides from occurring in the future anywhere in the world.

The next step must be for the international community—though still present in Bosnia and Herzegovina—to show greater resolve and capacity to help maintain Bosnia and Herzegovina as a sovereign, unified state.

Currently, I cannot say I am satisfied with the level of political engagement among the international community. Too often, it relies on working through the internal leadership of Bosnia’s institutions—while ignoring the persistent obstructions from political elites.

We face daily political obstruction, particularly from the ruling elite in Republika Srpska and also from nationalist elements in the Croat-majority areas of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. These factions consistently block the implementation of constructive decisions at the state level—decisions that would move Bosnia and Herzegovina in the direction it desires and deserves.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is geographically in Europe. It is in the very heart of Europe—but it is still not a member of the European Union. It must become a member.

We must all work toward that goal. If Bosnia and Herzegovina can join the EU, many problems in both the Balkans and Europe will be alleviated. I repeat: I am not satisfied with the international community’s impact on the present situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a centuries-old country with a history that stretches back more than a thousand years.

Bosnia and Herzegovina has a turbulent and dynamic history, but it has always existed. It is the oldest of all the neighbouring countries in the Balkans. However, today, we live surrounded—both internally and externally—by forces that seek to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina into parts.

However, this will not happen. As long as we, the sons and daughters of Bosnia, live anywhere in the world, we will fight for our state—our homeland—because it is our only homeland.

As a citizen of Srebrenica, I contribute in the ways I can. I have been working for over 30 years on illustrations that depict the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, focusing particularly on the genocide in Srebrenica, on proceedings at the Hague Tribunal, and other key decisions related to Srebrenica.

I have created over 500 illustrations and published three books featuring my work. These books are bilingual, in Bosnian and English. They are housed in libraries worldwide. I have also held 30 exhibitions of my illustrations.

People have responded positively to my work, which shows me that I am doing my part. I am not trying to ease the conscience of those within the United Nations, nor do I claim to have saved lives. However, at the very least, I want to help prevent such tragedies from happening again in the future.

Today, we are witnessing the proceedings at the International Court of Justice related to Gaza, where the international community is again struggling to prevent the daily killing of innocent civilians—whether by bullets or bombs.

I continue to write for various Norwegian news outlets, contributing information and perspective on what is happening in Bosnia and Herzegovina. I have given my utmost because Srebrenica and Bosnia and Herzegovina live deeply within me. They run through my veins, and I will never stop.

I wish no harm on anyone, but what happened to us in Srebrenica and Bosnia and Herzegovina is unforgettable. It will remain part of our collective memory.

Jacobsen: Thank you for your time.

Meholjić: Thank you for the interview.