The West’s Titanium Loophole Is Getting Harder to Defend

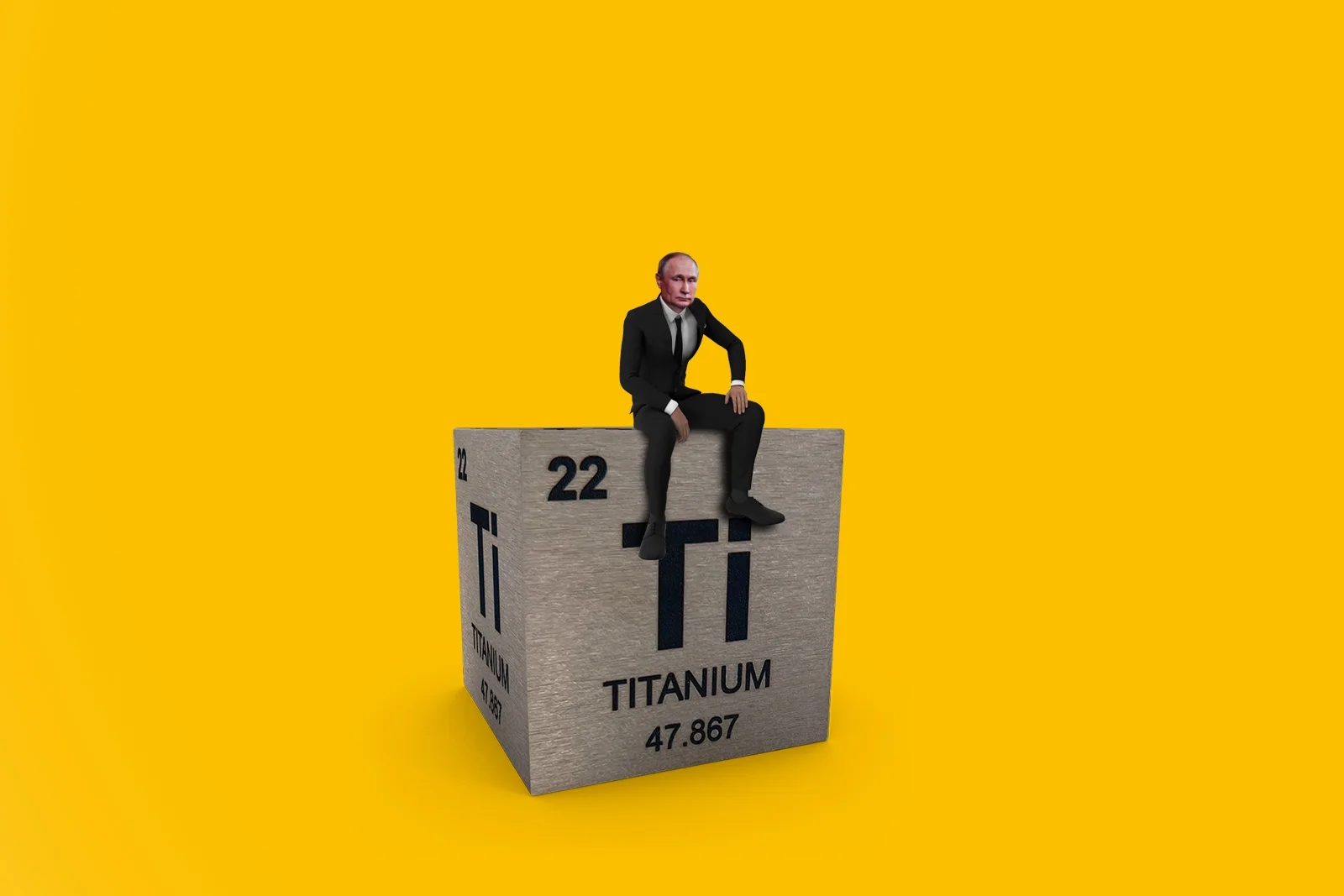

As the war in Ukraine grinds on, a long-standing carve-out in the Western sanctions regime is drawing fresh fire: titanium. What began as a practical exemption to protect aerospace supply chains now looks, to critics in Washington, Brussels, and London, like a costly inconsistency that props up a key Russian industry while the West vows to squeeze Moscow’s war economy.

The timing is not incidental. President Trump—said by aides to be increasingly impatient with Vladimir Putin and eager to force the Russian leader’s hand—is expected to unveil a tougher round of penalties on Russia, sharpening the debate over which sectors remain untouched and why.

For nearly three years, the allied economic campaign has focused on energy and finance, severing Russian oil revenues and isolating banks and industrial champions. Titanium, however, remained largely outside those efforts. The rationale was straightforward: the metal is indispensable to advanced manufacturing, especially in aviation and defense, and sudden restrictions risked snarling production lines on both sides of the Atlantic.

That rationale is losing altitude.

Titanium is prized for its strength-to-weight ratio and resistance to corrosion; it is not rare, but it is difficult and costly to refine. Russia, through VSMPO-AVISMA—the world’s largest producer of aerospace-grade titanium—has been a dominant supplier for decades. Before the 2022 invasion, the Urals-based firm was believed to furnish as much as 60 percent of Airbus’s titanium and roughly 80 percent of Boeing’s, according to industry officials. Fearing a supply shock, early sanctions packages left titanium outside the scope.

Since then, the ground has shifted. Airbus and Boeing have diversified aggressively, tapping U.S., European, and Asian producers and drawing down stockpiles. Airbus now reportedly sources about 20 percent of its titanium from Russia and has signaled further reductions in this supply. Boeing, for its part, has leaned into domestic and allied suppliers. “Major aerospace firms have restructured their supply chains significantly,” a senior European trade official said. “The risk of serious disruption has diminished.”

Investment followed the pivot. France’s Aubert & Duval upgraded a critical forging press that once relied on Russian inputs. U.S. companies, such as ATI Titanium and TIMET, expanded their smelting and forging capacities. Producers in Japan, Kazakhstan, and Bahrain have also increased output, giving Western buyers more options than they had in 2022.

Those changes have begun to bite inside Russia. Analysts say VSMPO’s sponge production has fallen sharply since the war began; exports have declined as financing tightens and Western demand fades. Much of the company’s output now serves domestic industries or moves through secondary markets in China. Yet Russia remains an important player in the titanium trade—and a continuing source of hard currency for the Kremlin.

Hence the policy dilemma. “There’s a growing view that the titanium carve-out no longer reflects market reality,” said one EU official familiar with ongoing discussions. “We’re already moving away from Russian supply. The next step is formalizing that shift through coordinated sanctions.” Advocates frame the question as one of strategic coherence: if the aim is to starve the war machine, leaving a marquee dual-use material untouched sends the wrong signal. “If strategic autonomy is the goal,” a defense analyst argued, “then consistency across critical materials is key. Titanium shouldn’t be the exception.”

Skeptics do not dismiss the direction of travel; they question the tempo. Some European firms, particularly in specialized tiers of the supply chain, remain partly reliant on Russian feedstock and argue for a phased approach with clear transition periods. Even many of these voices, though, concede that the industry is moving—and that policy is likely to catch up.

The European Commission had been expected to publish its nineteenth package of Russia sanctions on Wednesday, September 17, but officials now say the measures are more likely at the end of the week. “Depriving Moscow of the funds to wage a war is essential to end this conflict,” Kaja Kallas, the EU’s top diplomat, said. Her remarks followed European Parliament President Roberta Metsola’s meetings in Kyiv with President Volodymyr Zelensky and Rada Chairman Ruslan Stefanchuk; she also addressed the Verkhovna Rada on September 17. “Europe will not back down in its support to Ukraine,” Metsola said. “We will continue to weaken Russia’s war machine through coordinated and strong sanctions.”

London has moved in parallel. The British government has rolled out roughly 100 new designations aimed at Russian revenues and procurement networks, including measures against the so-called shadow fleet that ferries oil and a tranche of electronics and chemical suppliers. On Friday, September 12, the UK added sanctions on 70 additional ships linked to the shadow fleet and targeted about 30 entities and individuals supplying components—electronics, chemicals, explosives—used to manufacture missiles and other weapons systems.

There is still no outright British ban on Russian titanium. The UK has, however, tightened restrictions on Russian metals such as aluminum, copper, and nickel, and increased scrutiny of the titanium trade to align with allies. In a joint step on April 12, 2024, the UK and the U.S. announced stricter limits on Russian metal exports; titanium and platinum-group metals were excluded at the time, a nod to lingering supply-chain concerns. For now, titanium remains an outlier—even as reliance on Russian supply continues to shrink.

Momentum is also building within legislatures. In July, a coalition of European lawmakers urged a formal reassessment of the exemption and called on the Commission to coordinate with counterparts in Washington and London on a tailored package. Behind closed doors, officials say the conversations are no longer hypothetical; the technical work—definitions, licensing pathways, timelines—is already in motion.

The practical effect would be to close one of the last major channels through which Russia sells a strategic commodity directly to Western customers. “A coordinated move by the U.S., EU, and UK would mark a turning point,” a former U.S. trade official said. “It would close a significant gap in the sanctions framework and send a clear signal that no sector is off limits indefinitely.”

Sanctions rarely deliver immediate results; they tighten over time. But as the allies recalibrate an economic strategy for a long war, titanium looks like the next domino. The question is no longer whether the carve-out can be justified. It is when—and how fast—the exemption ends.