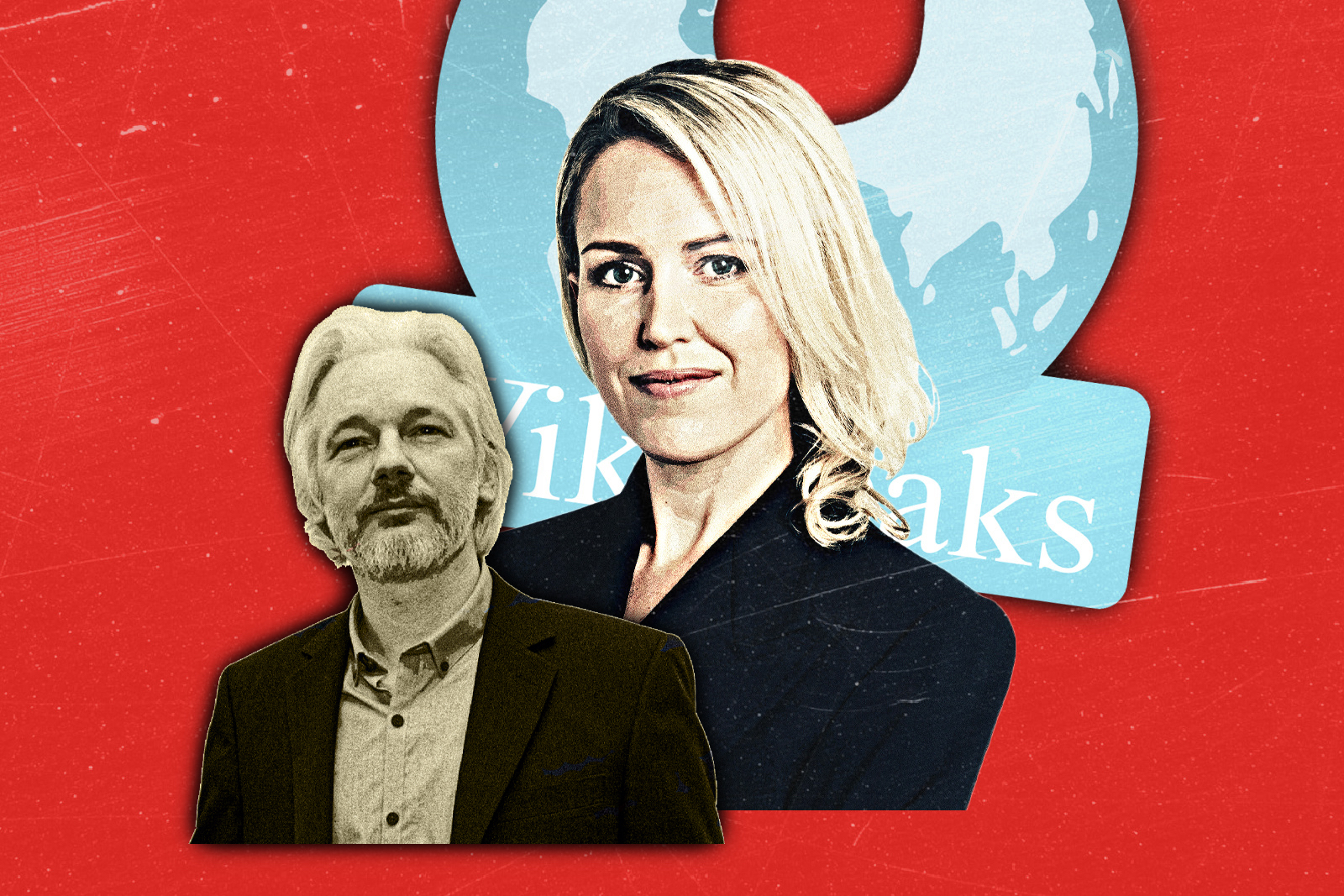

A Political Solution for Assange: Jennifer Robinson at the National Press Club

It was telling. Of the mainstream Australian press outlets, only David Crowe of the Sydney Morning Herald turned up to listen to Jennifer Robinson, a lawyer who has spent years representing Julian Assange. Since 2019, that representation has taken an even more urgent note: to prevent the WikiLeaks founder from being extradited to the United States, where he faces 18 charges, 17 confected from the archaic Espionage Act of 1917.

In addressing the Australian National Press Club, Robinson’s address, titled “Julian Assange, Free Speech and Democracy,” was a grand recapitulation of the political case against the WikiLeaks founder. Followers of this ever-darkening situation would not have found anything new. The shock, rather, was how ignorant many remain about the chapters in this scandalous episode of persecution.

Robinson’s address noted those blackening statements from media organisations and governments that Assange was paranoid and could leave the Ecuadorian embassy, his abode for seven years, at his own leisure. Many were subsequently “surprised when Julian was served with a U.S. extradition request.” But this was exactly what WikiLeaks had been warning about for some ten years.

In the Belmarsh maximum security prison, where he has resided for nearly four years, Assange’s health has declined further. “Then last year, during a stressful court appeal hearing, Julian had a mini stroke.” His ailing state did not convince a venal prosecution, tasked with “deriding the medical evidence of Julian’s severe depression and suicidal ideation.”

The matter of health plays into the issue of lengthy proceedings. Should the High Court not grant leave to hear an appeal against the June decision by former Home Secretary Priti Patel to order his extradition, processes through the UK Supreme Court and possibly the European Court of Human Rights could be activated.

The latter appeal, should it be required, would depend on the government of the day keeping Britain within the court’s jurisdiction. “If our appeal fails, Julian will be extradited to the U.S. – where his prison conditions will be at the whim of intelligence agencies which plotted to kill him.” An unfair trial would follow, and any legal process citing the First Amendment culminating in a hearing before the U.S. Supreme Court would take years.

The teeth in Robinson’s address lay in the urgency of political action. Assange is suffering a form of legal and bureaucratic assassination, his life gradually quashed by briefs, reviews, bureaucrats, and protocols. “This case needs an urgent political solution. Julian does not have another decade to wait for a legal fix.”

Acknowledging that her reference to the political avenue was unusual for a lawyer, Robinson noted how the language of due process and the rule of law had become ghoulish caricatures in what amounts to a form of punishment. The law has been fashioned in an abusive way that sees a person being prosecuted for journalism in a hideously pioneering way. Despite the UK-U.S. Extradition Treaty’s prohibition of extradition for political offences, the U.S. prosecution was making much of the Espionage Act. “Espionage,” stated Robinson, “is a political offence.”

The list of abuses in the prosecution is biblically lengthy. Robinson gave her audience a summary of them: the fabrication of evidence via the Icelandic informant and convicted embezzler and pedophile Sigurdur “Siggi” Thordarson; the deliberate distortion of facts; the unlawful surveillance of Assange and his legal team and matters of medical treatment; “and the seizure of legally privileged material.”

Much ignorance about Assange and the implication of his persecution is no doubt willed. Robinson’s reference to Nils Melzer, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, was apt. Here was a man initially sceptical about the torture complaint made by Assange and his team. He had been convinced by the libel against the publisher’s reputation. “But in 2019, he agreed to read our complaint. And what he read shocked him and forced him to confront his own prejudice.”

Melzer would subsequently observe that, in the course of two decades working “with victims of war, violence and political persecution, I have never seen a group of democratic States ganging up to deliberately isolate, demonise and abuse a single individual for such a long time and with so little regard for human dignity and the rule of law.”

The concern these days among the press darlings is not press freedoms closer to home, whether they be in Australia itself, or among its allies. The egregious misconduct by Russian forces in the Ukraine war or China’s human rights record in Xinjiang are what counts. Villainy lies elsewhere.

The obscene conduct by U.S. authorities, whose officials contemplated abducting and murdering a publisher, is an inconvenient smudge of history best ignored for consumers of news down under. The Albanese government, which has continued to extol the glory of the AUKUS security pact and swoon at prospects of a globalised NATO, has shelved any “political solution” regarding Assange, at least in any public context. The U.S.-Australian alliance is a shrine to worship at with reverential delusion, rather than question with informed scepticism. The WikiLeaks founder did, after all, spoil the party.

On a cheerier note, those listening to Robinson’s address reflected a healthy political awareness about the tribulations facing a fellow Australian citizen. The federal member for the seat of Kooyong, Dr. Monique Ryan, was present, as were Senators Peter Whish Wilson and David Shoebridge. As Ryan subsequently tweeted, “An Australian punished by foreign states for acts of journalism? Time for our government to act.”

Others were those who have been or continue to be targets of the national security state. The long-suffering figure and target of the Australian security establishment, Bernard Collaery, put in an appearance, as did David McBride, who awaits trial for having exposed alleged atrocities of Australian special service personnel in Afghanistan.

Such individuals have made vital, oxygenating contributions to democratic accountability, of which WikiLeaks stands proud. But any journalism that, as Robinson puts it, subjects “power to scrutiny, and holding it accountable,” is bound to incite the fury of the national security state. Regarding Assange, will that fury win out?