Africa’s Rising Political Violence

The rising propensity for political violence in much of Africa is a worrying trend that has received less attention in the international media than it deserves. Al Shabaab and Boko Haram are frequently mentioned in the media, but the predisposition for rising violence among and between a variety of groups throughout the continent is equally important – and has profound implications for Africa, as well as the global war on terror.

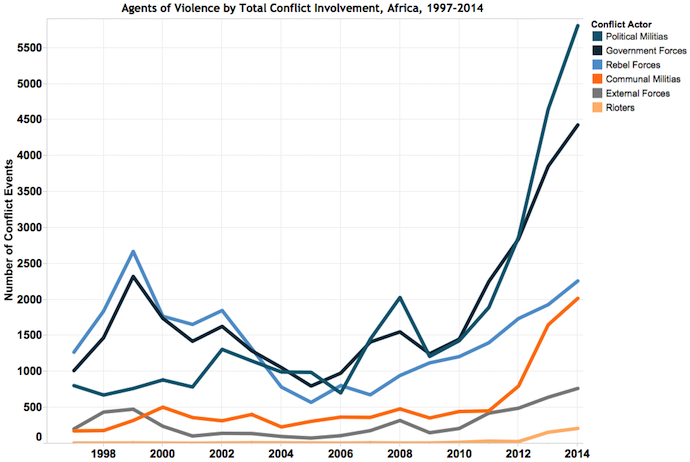

The Armed Conflict Location and Data Event Project (ACLED) has done good work on this subject, chronicaling various aspects of political violence in Africa since 1997. As is noted in the first figure, both the number of conflict events and the actors responsible for them have risen dramatically since 2006 in Africa, with the largest rise coming from political militias and the government forces opposing them. Since 2006, both of these groups have been responsible for a more than 500% rise in the number of events.

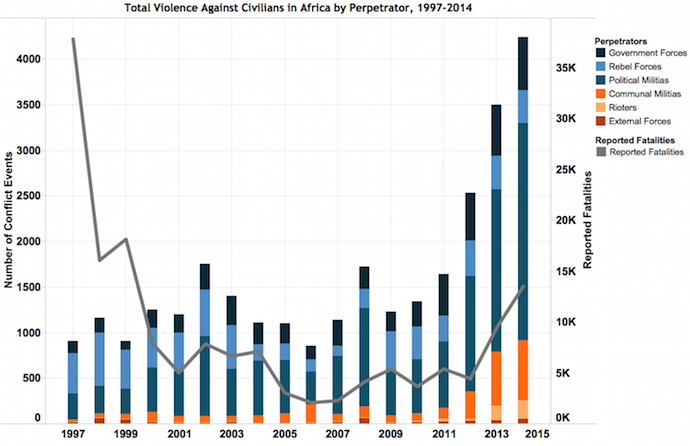

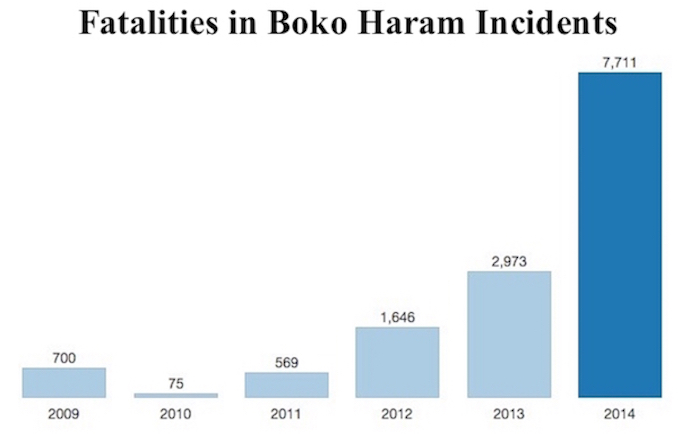

As is noted in the second figure, the rise in the number of events has corresponded with a dramatic rise in fatalities. While the majority of these may be attributed to political militias, a significant rise in fatalities can be attributed to communal militias and government forces. Nearly 40,000 were killed by various perpetrators in 2014 – also a more than 500% rise since 2006. As is noted in the third figure, the number of fatalities attributable to Boko Haram has risen exponentially, from just 75 in 2010 to more than 7,700 in 2014. While daily killings may make local news, it is rarely reported with regularity in the international media.

The implications of these dramatic statistics are numerous, since such political violence is having an increasing significant impact on the ability of a variety of African states to combat the problem:

1. Many of these states are either failed or failing, and have too few resources to devote to address the violence through state resources.

2. Police and military personnel are easy prey for arms traders and others who wish to circumvent what law and order does exist, making attempts to impose law and order all the more challenging.

3. The region’s increasingly porous borders make it doubly difficult to establish and maintain gains on the part of government forces seeking to stem the flow of rebels and military hardware.

4. The inevitable increase in refugees fleeing the violence adds additional strain to government resources, and negatively impacts neighboring countries which may not be part of the violence.

There is a swathe of states — from Africa’s east coast to West Africa — that are effectively ungovernable, what I call the ‘African Confederation of Failed States.’ What they all have in common are a combination of a lack of perceived governmental legitimacy, terrible corruption, a topography that defies border security, and either being Muslim states or in proximity to Muslim states. The political scientist Samuel Huntington believed that countries neighboring Muslim states are more likely to experience cross-border conflict.

Islamic extremists have seized the opportunity to wreak havoc in countries where they know there is a good chance they will be successful, combining chronic dissatisfaction with existing governing authorities with brute force. Their timing is good, in the sense that donor countries are suffering from “terrorism fatigue,” running out of financial resources to combat the problem as well as the political will to carry on fighting.

So we are at a real crossroads. The bloodletting is spreading in Africa: Algeria, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Libya, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia — the list is getting longer. Similar to what was the case vis-a-vis the Arab Awakening, forces pent-up for decades have been unleashed in Africa, and may very well be unstoppable. The West certainly seems powerless to do much of anything about it.

The core problem is corruption, because no fight against terrorism has been or can be successful in highly corrupt countries. Resources either fail to end up in the right place, or disappear altogether. In Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, the best scoring African country (Botswana) is ‘moderately’ corrupt. Of Africa’s 57 countries, 46 are judged to be either corrupt or highly corrupt, including 4 of the worst 6. When corruption is so rampant, the state becomes an integral part of the problem.

It would be nice to be able to say that the threat of Islamic fundamentalism has peaked in Africa, and that the worst is over, but given the current state of affairs that simply is not the case. In all likelihood, the threat will grow — considerably — in the years to come. Given the scope of corruption and all the difficulties associated with combatting the problem, the region’s security services will unfortunately continue to be relegated to the role of firemen — putting out fires, instead of preventing them. And Africa’s people will continue to suffer the most.