Books

Alexander Cockburn, 1941-2012

“For Chaos heard his voice: him all his Traine…Follow’d in the bright procession to behold…Creation, and the wonders of his might.” – Paradise Lost, John Milton

It was fitting that writer and critic Alexander Cockburn’s funeral should include a passage from Milton. For more than 50 years, Cockburn combined polished, erudite writing with fierce political insight in the tradition of the great 17thcentury English polemicist. Cockburn died July 20 in Germany at age 71, following a two-year struggle with cancer. He was buried July 28 in his beloved Petrolia, Ca.

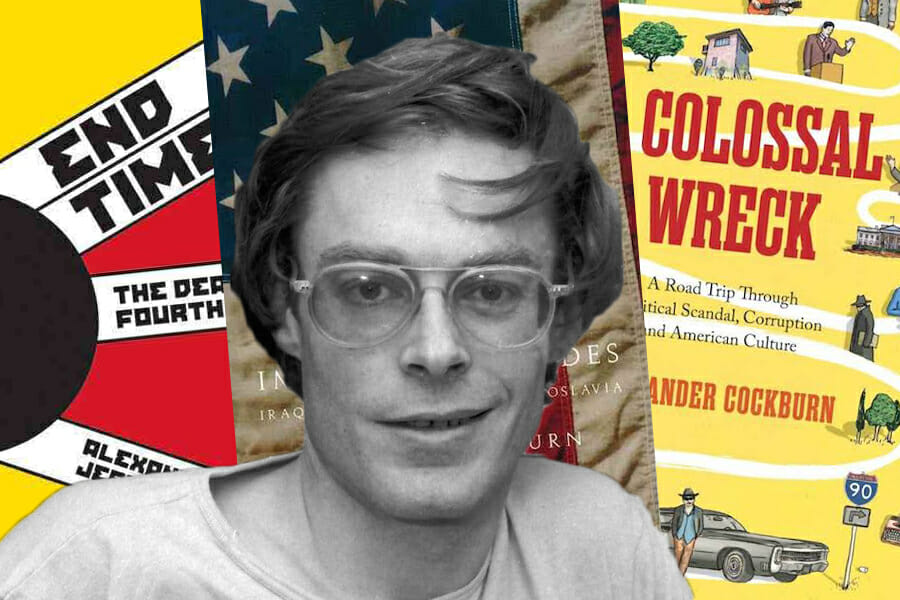

It is hard to sum up his career because it was catholic in true meaning of that word: all embracing. He wrote for newspapers in England, New York’s Village Voice, the Wall Street Journal, and the Nation, and, along with Jeffery St. Clair, founded the investigative publication, CounterPunch. For more than 50 years, Cockburn was a relentless critic of U.S. foreign policy, opposing the Yugoslav War, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the recent war in Libya.

He was particularly critical of Israel, and for that earned the undying enmity of people like Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, who called him an anti-Semite.

Cockburn responded by publishing a book of essays entitled The Politics of Anti-Semitism, commenting that one could always tell when Israel was misbehaving because of charges of anti-Semitism thrown at its critics.

He was born in Scotland, the oldest of three sons of Claud and Patricia Cockburn. He had two sisters from his father’s previous marriages. The family moved to Youghal, County Cork in 1947, and Cockburn lived there until he went to Oxford in 1960. Graduating from Oxford in 1963 with a degree in literature and language, he worked as a journalist in London. He moved to the United States in 1972.

For 12 years Cockburn wrote a column for the Village Voice called “Press Clips,” which dismantled the myth of objective journalism and exposed the incestuous relationship between U.S. foreign and domestic policy and the media. The column sent shockwaves through the fourth estate in much the same way as A.J. Liebling’s critical writings had done in a previous generation. He left the Voice in 1984 and began writing a column named after one of his father’s novels, Beat the Devil, for the Nation. He continued to do so up until a few days before he died. His last column appeared in the Nation July 30.

In 1996 he and Jeffery St. Clair founded CounterPunch along with Jeffery, a combination print and on-line investigative magazine that features some of the leading writers on the Left.

The Cockburn family was sort of a journalism collective. His father Claud was probably the best front-line reporter during the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War—and the competition was rather steep for that designation—and a brilliant essayist on everything from British foreign policy to Irish agricultural practices. The elder Cockburn’s ability to write about virtually anything paralleled Alexander’s career. As Nation editor and publisher Katrina vanden Heuvel told the Associated Press, “His range was extraordinary. He could write about fox hunting, and he could write about intervention.”

Cockburn wrote several books, including Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press (with St. Clair), A Short History of Fear, Corruptions of Empire, and End Times: The Death of the Fourth Estate.

Alexander’s brothers, Patrick and Andrew, are also journalists of considerable merit. Patrick, a Middle East expert for the Independent, spent several years in Iraq, writing an outstanding book on Shia leader Muqtada al-Sadr. He is currently based in Britain and continues to report and comment on the Middle East. Andrew, an expert on all matters military, has written several investigative books, including a recent one on former U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, as well as a study of U.S.-Israeli covert relations, and a book on Saddam Hussein.

His Frontline story “Drugs, Guns and the CIA”—done in collaboration with his wife, Leslie Cockburn— is probably the best study of the long and sordid relationship between American intelligence and drug dealers during the U.S. war in Laos and the Contra War against Nicaragua.

Obituaries have labeled Cockburn a “contrarian,” although that term is inaccurate. He was famously fierce and could be absolutely scathing— woe betide those who challenged him in print—but his politics were always coherent and deep-seated. If he disagreed with you it wasn’t because he was being contrary, it was because he didn’t agree with your politics.

He was always suspicious of orthodoxy—a sentiment that he shared with Milton—which many times put him at odds with others on the Left. He was roundly criticized for his doubts about global warming, but his stance had nothing to do with crankiness and everything to do with his mistrust of group think. He was suspicious of assumed truths, and when he expressed those sentiments about global warming he was widely denounced. It was as if he had gone to Lourdes and done something rude to the Virgin Mary. Criticism of independent thinking always made him dig in his heels and if you wanted a good old-fashioned Donnybrook, Alex was your man.

His funeral was very much an Alexander Cockburn affair. The speeches were short and the funeral procession—led by his daughter, Daisy—was headed up by a yellow fire engine. A long line of cars followed, winding their way through the rolling Northern California hills to a flat plain surrounded by high hills crowned with ocean fog. “Over to the glory land” was sung and Cockburn’s beautifully handcrafted coffin—embossed with a typewriter—laid to rest. We shall not see his like again in our time.