An Economic Plan for Florida’s Next Governor

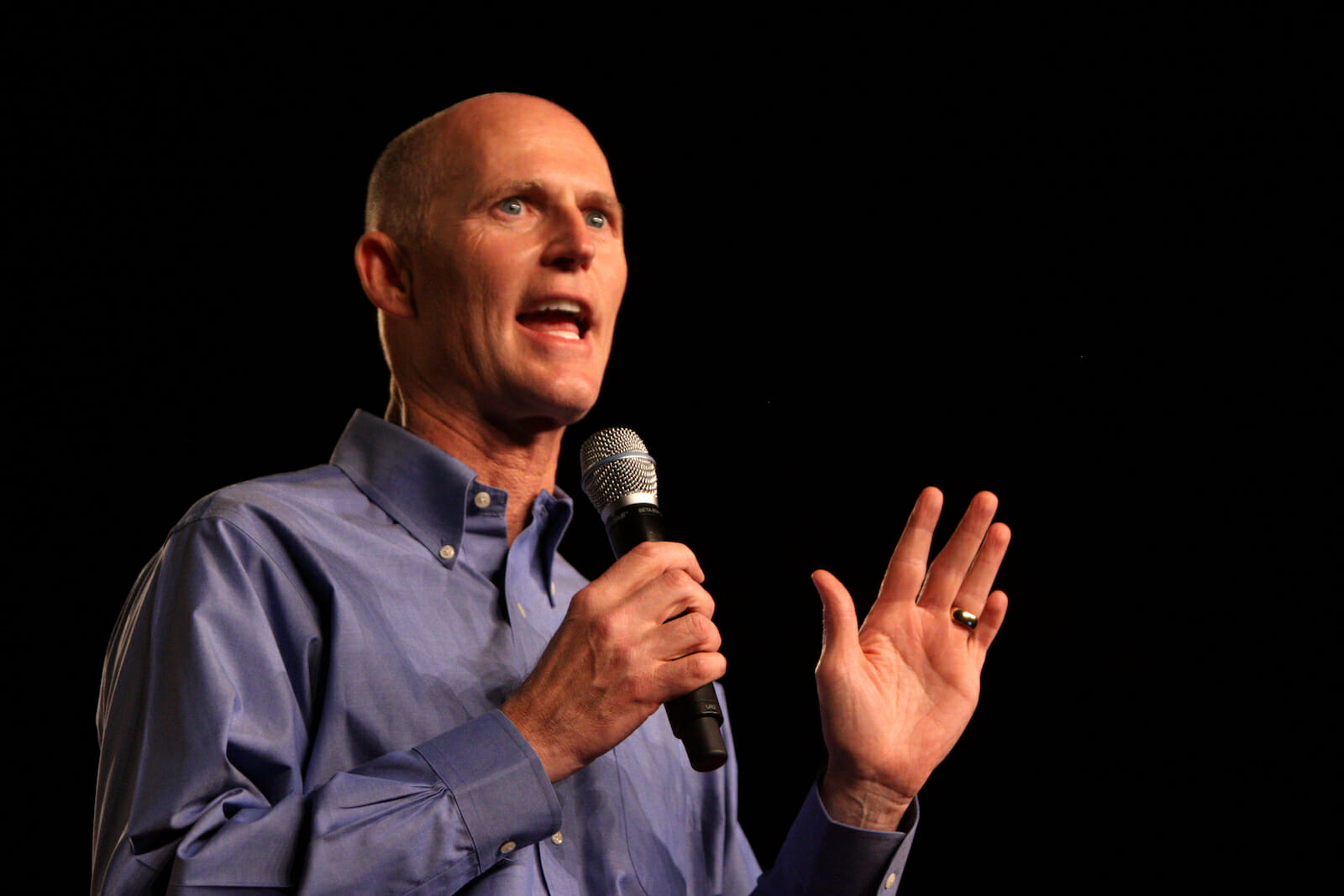

As Gov. Rick Scott’s political opponents build campaigns and settle on a competing vision for Florida, they should take the summer to write an economic plan that promises a better future for the state’s most precious social capital—its youth.

Superficially, Florida’s economy appears to be in recovery. In April, the state’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 7.2 percent, the lowest since September 2008. “2013 is shaping up to be a year for Florida to transition back into higher growth,” said economist Sean Snaith, director of University of Central Florida’s Institute for Economic Competitiveness, thanks in part to a turnaround in the housing market.

But the state’s underlying sources of weakness remain. Many new jobs are in traditional Florida industries like leisure and hospitality, construction, and real estate. These boom-and-bust sectors have long produced an erratic source of income for households across the state. Their chronic instability complicates saving and investment for families and for state budget managers. It is likely, moreover, that the state’s golden era of real estate is long-gone. The state is already 91 percent urbanized. Soon after the 2008 recession, Florida lost population for the first time since World War II.

Worse, tens of thousands of discouraged workers—many of them recent high school and college graduates—have quit the state’s labor force. According to The Tampa Bay Times, the civilian population sixteen and older increased 218,000 in 2012, but the labor force grew by only 96,000. Many of the state’s brightest public university graduates have left the state in search of better opportunities.

An alternative measure of unemployed computed by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, called U-6, incorporates “total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers, plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of the civilian labor force plus all marginally attached workers.” From the second quarter of last year to the first quarter of this year, Florida averaged 15.5 percent—one of the country’s worst U-6 state records. To realize a new period of high, sustainable growth that create good-paying, benefits-rich jobs for young Floridians, the state needs to build 21st century economic zones. Tomorrow’s tech-savvy, ever-mobile college graduates want to build a career beyond Disney World.

Central Florida has the potential to be one such state-of-the-art economic driver for the state. The I-4 corridor, one of the most storied demographics in American politics, is already home to one of the most dynamic, diverse workforces in the country. Spanish, Vietnamese, and Hindi are exchanged on a typical day in downtown Orlando. Tampa has a long history of Cuban-American commerce. Puerto Rican entrepreneurs continue to move to central Florida in droves, enriching the area’s politics and culture. The I-4 corridor boasts legions of hotel rooms and convention centers, as well as easy access to the rest of the world at Orlando International Airport.

For central Florida to attract the biggest players in the knowledge economy, however, it needs a menu of reforms in the areas of education, transportation, and economic incentives. First, consider the host of problems facing the region’s flagship university, University of Central Florida: scholarship funding shortages, chronic tuition hikes, large class sizes, and recent legislation raising the SAT score cutoff for the Florida Bright Futures scholarship. These issues have reduced student morale to an all-time low. Many UCF students fail to graduate—the school’s four-year graduation rate was only 35 percent last year. University of South Florida fared no better, graduating only 34 percent.

Without redress of these grievances, the best and brightest Floridians will continue to move out of state. Florida leaders should follow the template provided by North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park—one of the hottest economic zones in the South, built specifically to capture and harness the creativity of young people. When Tar Heel Governor Luther Hodges announced the Research Triangle Park, he said, “two thirds of these young people trained in science at these three institutions [Duke, North Carolina State, and the University of North Carolina] are forced to leave North Carolina, and indeed the entire South, to find suitable employment.”

The Research Triangle Park owes much of its economic success to the EPA’s 1965 decision to locate its 509-acre Environmental Health Sciences Center there, but without a trio of world-class universities as neighbors and partners, the Park would not have grown. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Duke University, and North Carolina State University were and are crucial catalysts. Florida now hosts one of the largest state university systems; its education administrators should take care not to sacrifice quality for quantity.

Second, central Florida needs to embrace public transit as part of a greener, more efficient transportation network. When completed, SunRail will be a key plank in this reform. Additionally, the I-4 corridor needs reform to speed up the East-West transfer of ideas and people: a Tampa-Orlando high-speed rail system, incentives for hybrid and electric cars, incentives for carpooling, and better bicycle access.

Finally, central Florida needs to diversify its university research focus. The region has had a UCF-affiliated research park since 1978, but the local tourism industry has always overshadowed it. The park’s singular focus on defense industry research has left it vulnerable to federal budget cuts and economic downturns.

Central Florida has the natural and human resources to become a national research center in solar energy, agriculture, health care, and other areas. It needs state patronage and leadership, partnered with entrepreneurial muscle, to develop these sectors. For example, the state’s solar industry has slowed dramatically due to lack of incentives. New Jersey, a state rarely associated with sunshine, surpasses Florida in every major solar industry category monitored by the Solar Energy Industry Association. In fact, Florida does not even crack the top ten in any state ranking. Without strong private partners, Florida’s Solar Energy Center will not have a proving ground for its innovations. Perhaps the Center should also consider relocating its Cocoa facilities to Orlando in order to raise visibility and improve public access.

Florida’s long-term economic development depends on innovation. Its youth are ready for a 21st century economy and willing to leave the state to find it. The next governor should develop central Florida as a headquarters for high-tech research and a talent magnet for the state. North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park provides a model for cultivating just this sort of knowledge economy in the South.