Media

Before Breitbart, there was the Charleston News and Courier

Conservatives who dislike Donald Trump like to blame the president and his Breitbart cheering section for the racial demagoguery they see in today’s Republican Party.

For example, New York Times columnist David Brooks lamented the GOP’s transformation over the past decade from a party that had always been decent on racial issues to one that now embraced “white identity politics.”

I respect Brooks and read him regularly, but on this issue he and his ideological allies have a blind spot. They ignore overwhelming evidence showing the central role racial politics played in the Republican Party’s rise to power after the civil rights movement.

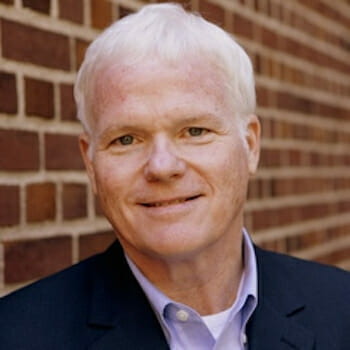

In my book Newspaper Wars: Civil Rights and White Resistance in South Carolina, I write about the white journalists who helped revive the GOP in one Deep South state. Their story shows how prominent voices of the conservative movement have long harnessed racial resentment to fuel the party’s political ascendancy.

A journalistic mouthpiece for segregation

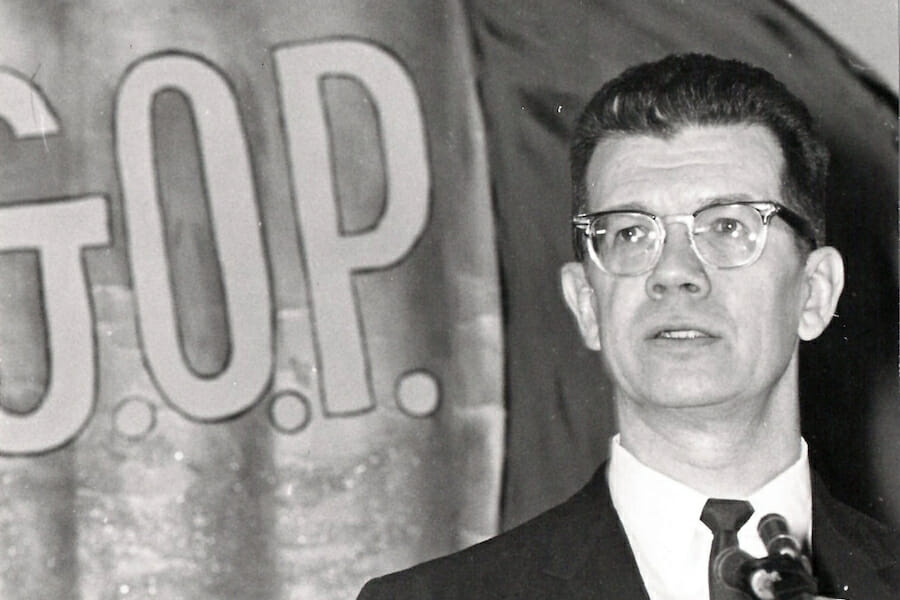

In 1962, Republican William D. Workman Jr. launched a long-shot bid for a U.S. Senate seat in South Carolina. For more than eight decades, the Democratic Party had been the only party that mattered in state politics. To most white voters, it represented the overthrow of Reconstruction and the restoration of white political rule.

Yet Workman nearly defeated a two-term Democratic incumbent. It was a turning point that signaled the GOP’s reemergence as a competitive force in the region.

The nation’s top political reporter, James Reston of The New York Times, traveled to South Carolina to examine this new GOP in the Deep South. He called Workman a “journalistic Goldwater Republican.” It might seem like an odd description, but it fit the candidate perfectly.

Before he joined the senate race, Workman had been the state’s best-known political reporter. He had also been working secretly with GOP allies to build the party in South Carolina and rally support for Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, leader of the GOP’s rising conservative wing.

In the late 1950s, Workman and his boss, Charleston News and Courier editor Thomas R. Waring Jr., were staunch segregationists who had found a political ally in William F. Buckley Jr., conservative editor of a new journal, National Review.

As political scientist Joseph E. Lowndes notes, National Review was the first conservative journal to try to link the southern opposition to enforced integration with the small-government argument that was central to economic conservatism.

In 1957, Buckley delivered the magazine’s most forthright overture to southern segregationists. In an editorial on black voting rights, Buckley called whites “the advanced race” in the South and said whites, therefore, should be allowed to “take such measures as necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas in which it does not predominate numerically.” In Buckley’s view, “the claims of civilization supersede those of universal suffrage.”

In the News and Courier, Waring described the editorial as “brave words,” but Buckley’s argument created a firestorm within the conservative movement. His brother-in-law, L. Brent Bozell, condemned the editorial in the pages of Buckley’s own magazine. Bozell said Buckley’s unconstitutional appeal to white supremacy threatened to do “grave hurt to the conservative movement.”

Workman and the ‘great white switch’

Buckley and Goldwater began avoiding such overtly racist appeals, but it took longer for their southern allies to temper their rhetoric and master the use of racially coded language. In his 1960 book, The Case for the South, Workman wrote that African-Americans remained “a white man’s burden” – a “violent” and “indolent” people who needed guidance from their white superiors.

Two years later, Workman rallied local and national Republicans to his banner in the senate race. At the time, the tiny GOP in South Carolina was run by conservative businessmen who had migrated to the Palmetto State from the North. They embraced Goldwater’s call for lower taxes, weaker unions and smaller government, but the Republicans lacked credibility with white voters who cared mostly about segregation and white political rule.

Workman’s 1962 campaign changed that. He united the state’s racial and economic conservatives, a political marriage that would fuel the party’s dramatic growth in South Carolina and the nation over the next two decades.

As historian Dan T. Carter contends, “even though the streams of racial and economic conservatism have sometimes flowed in separate channels, they ultimately joined in the political coalition that reshaped American politics” in the years after the civil rights movement.

Workman was thrilled by the letters he received from northern conservatives who embraced his campaign. One of those was William Loeb, editor of New Hampshire’s Manchester Union-Leader, who told Workman the GOP should become “the white man’s party.” Loeb said his proposal would “leave Democrats with the Negro vote,” but give the Republicans the white vote and “white people, thank God, are still in the majority.”

Buoyed by the surprising strength of Workman’s campaign, South Carolina’s junior senator, Strom Thurmond, abandoned the Democratic Party in 1964 and joined the Republicans. Sixteen years earlier, Thurmond had left the Democrats briefly to run for president as a “Dixiecrat” on the States’ Rights ticket. His surprise announcement in 1964 signaled the start of what political scientists call the “great white switch.”

As more African-American voters joined the Democratic Party, southern whites moved to the GOP. William Loeb was getting his wish.

Reagan and the Neshoba County Fair

By the late 1970s, Ronald Reagan had united former segregationists with economic and social conservatives to create a political movement that would dominate American politics. Reagan built this coalition in part through the use of coded rhetoric tying race to such issues as crime, welfare and government spending.

In 1980, he launched his fall presidential campaign at the Neshoba County Fair near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Sixteen years earlier, three civil rights activists had been murdered in Neshoba County and buried in an earthen dam. Reagan used his visit to declare his support for states’ rights – a phrase indelibly linked to Thurmond’s Dixiecrat campaign of 1948.

In a 2007 column, Brooks angrily disputes any notion that Reagan’s Neshoba County trip was a dog-whistle appeal to white racial resentment in the post-civil rights era. He calls such claims a “slur” and a “calumny.” Reagan’s campaign was notoriously disorganized, Brooks argues. The candidate had planned to launch his general election campaign discussing inner-city problems with the Urban League, not preaching states’ rights in Neshoba County.

Maybe he’s right. Perhaps it was just a scheduling mishap. But on the question of race and politics, I’m more inclined to believe Lee Atwater, the late political strategist from South Carolina.

Atwater served as White House political director under Reagan and chief strategist for President George H. W. Bush’s 1988 campaign. In a 1981 interview with political scientist Alexander Lamis, Atwater explained the evolution of coded racial language in political campaigns in the South.

“You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘nigger, nigger, nigger.’ By 1968 you can’t say ‘nigger’ – that hurts you, backfires,” Atwater said. “So you say stuff like forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract. Now, you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites…”

This is not to say that all Republicans are racist, or that economic, social and cultural issues played no role in the rise of the conservative GOP. But it is clear that racial resentment mattered to voters – a lot – and the Republican Party found ways to stoke that animus for political gain.

Donald Trump’s racial appeals may be more transparent. But in him, the legacy of conservative journalists like William Workman lives on.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.