Books

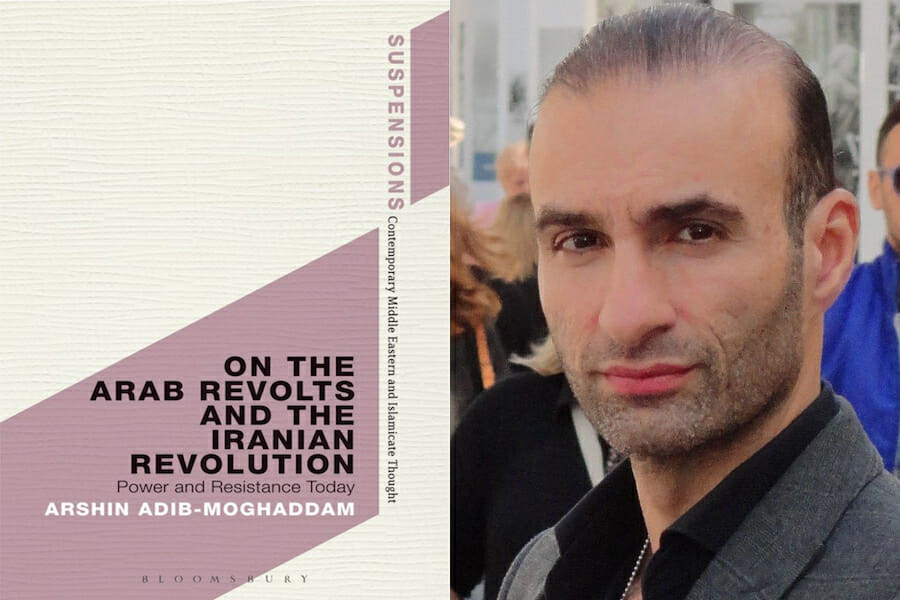

Book Review: ‘On the Arab Revolts and the Iranian Revolution’

From armed conflicts to peace processes, populist movements and violent repression, the Middle East has captivated and galvanized much of the world. Centuries have passed since the region’s ‘Golden Age’; a period in which its cities, markets, universities and libraries dwarfed those of Europe and significant advancements were made in the fields of medicine, mathematics, physics, optics, and numerous other disciplines. These achievements came about during a worldly and cosmopolitan era devoid of the politicoreligious authoritarianism that has been utilized to justify the region’s modern political systems.

Progress eventually waned and the Middle East began to fall behind Europe’s scientific and technological advancements. Crumbling economies led to a shifting political culture that was more interested in maintaining the status quo than expanding human knowledge. During the 19th century, the Middle East witnessed a moderate economic revival – European investments assisted in developing rail lines throughout the region as well as constructed the Suez Canal – which reinvigorated national economies. By the 20th century, the concessions made to the European powers during the region’s development sparked a drive toward nationalist politics that would, it was hoped, eventually replace the existing order.

Focusing their efforts to foster political and economic independence – concentrating wealth and power locally and upending foreign influence – was deemed more important than cultural and intellectual advancement. Central governments’ continued to consolidate power which led to corruption, nepotism and one-party political systems, eroding civil liberties and justice for many and catalyzing revolutionary movements.

In On the Arab Revolts and the Iranian Revolution, scholar Arshin Adib-Moghaddam – a professor in Global Thought and Comparative Philosophies at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies – has completed a thorough analysis comparing regional social movements: the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the Arab Spring – coupled with western social movements that also began in 2011. His work contextualizes the “global changes to forms of power and resistance” and theorizes that these contemporary events are “the beginning of the end of post-colonialism” in the Middle East and North Africa: “What is striking about [the Arab revolts] is that the entire Islamic complex is now directed towards democracy and social equality. Islam is realizing its latent social and cultural force, transforming itself into a ‘post-modernized Islam’ that is a significant departure from the deterministic, totalitarian ‘Islamism’ of previous generations which continues to linger on at the margins of the political mainstream.”

Understanding how these resistance movements came to be – a response to domestic repression and international disenfranchisement – runs contrary to the perception that Islam, in particular, and the Middle East, in general, are not compatible with democratic values. Moreover, he has written in ardent eloquence a fascinating and engaging theoretical retrospective that not only illustrates why “both domestic politics and international relations need to be reconstituted” and “opened up even further to critical approaches which appreciate different cultural experiences within a common universality,” but also reshapes the concept of power and resistance in the modern age. “In tone and syntax,” writes Adib-Moghaddam, “this type of post-modernized Islam has departed from mainstream Muslim politics in the twentieth century and the revolutionary Iranian variant.” Thus, what has occurred throughout the region changed the geopolitical environment to such a degree that the world must begin to re-conceptualize the Middle East, in which “emphasizing and then moving beyond the linkages between us and them, rather than perpetuating any supposed opposition, is vital.”

Collective action against totalitarian states stemmed from the fact that “resistance to injustice is a human trait.” The people’s desire to resist central governments does not solely reflect regional circumstances for “there is nothing particularly Iranian or Arab about these revolts and nothing European, western, or American about demands for democracy and social justice.” Despite the differences in the revolutions’ scope, similarities abound when looking at the people’s demands, the role of social media, and the strategies implemented by both sides when trying to incite and quell violence, yet most movements lost their steam and states, reversing their initial concessions, regressed [sans Tunisia] in a manner reminiscent to Algeria’s struggles since the 1980s and 1990s.

Free elections – a concession made by many seemingly outgoing regimes – led to the rise of Islamist groups that were eventually stamped down by military intervention, causing blood to be spilled in the streets across the region. A battered and exhausted population eventually acquiesced to a new centralized authority that had similar leaders, aggressive tactics and political strategies to that which the population had fought against at the revolutions’ outset. During this period of chaos, calls for stability replaced those for democracy and justice as the central tenet to these newly reorganized states.

The oppositionists, unwilling to relinquish all for which they had fought continued to apply pressure to the unremarkable leaders that replaced the previous brutally repressive regimes, were labelled terrorists, as a means for the government to justify their policies. These labels are effective in driving away international support for social movements – US conservatives were eager to applaud the re-emergence of an oppressive military regime in Egypt as long as Islamist groups remained marginalized, regardless of their electoral legitimacy. During these periods of uncertainty, the manner in which words are used to define an ideology will impact how it is perceived.

As Adib-Moghaddam points out in his assessment of US-Iranian relations: “To those who would say that Iran was associated with terror because the country supported a range of movements and organizations that use political violence in order to further their political aims, allow me to respond that ‘terrorism’ as a noun and ‘terroristic’ as an adjective are the terminological surface effect of discursive representations: they are concepts that emerge out of a particular politico-cultural configuration which commands its own signifying powers out of which the terror label and its derivatives are distilled…[I]n the reality invented for us, it is not the moral taboo that represents a country or movement as terroristic but the discourse which signifies the fundamental categories as ‘friend and foe,’ ‘terrorist and freedom fighter.’”

It is during tumultuous times that the concepts of ‘resistance’ and ‘terrorism’ become synonymous and tend to be driven by the imminence of the ‘other.’ Threats – real or perceived – have been utilized by both the United States and Iran since the 1979 Iranian revolution, where “colonizer and colonized” have repeatedly “engaged in a discursive war of attrition that was meant to ostracize the other side and to accentuate the supremacy of the respective self.” Over the years, both sides have utilized falsehoods about the other in order to reinforce questionable policies that are deemed justifiable due to the created perception of perpetual conflict.

The problem that comes to the forefront with the political strategy of demonizing the other is that the imagery is difficult to alter which has been witnessed in the backlash regarding the recent nuclear deal with Iran by hardliners interested in further propagating the perceived imminent danger this peaceful negotiation poses. Decreasing intra-state and inter-state antagonism, as Abid-Moghaddam shows, can occur once it is recognized that there is an “emergence of a universal, radical democratic space in which the resistance in one part of the world is linked to the resistance in a geographically distant area.” Upon this understanding and casting aside the perception of the “imminent neighbor” we may very well witness the decoupling of current geo-political thought away from ‘the west and the rest’ and accept a new concept of global resistance politics.

The relationship between religion and politics plays a very important role throughout the book, and to the author Islam [similarly to other world religions] encompasses ideas of knowledge and ethics that can make a society democratic or authoritarian. Religion can and has been co-opted by political movements for good and for evil, and the individual essays that make up On the Arab Revolts and the Iranian Revolution – the correlation between power, resistance, the demonization of the other, the perception of imminent threats, the desire for democracy and social justice – have been expertly articulated in explaining not only what drives human interests, but also how our understanding must be modified and refocused in response to an ever-changing world.