Books

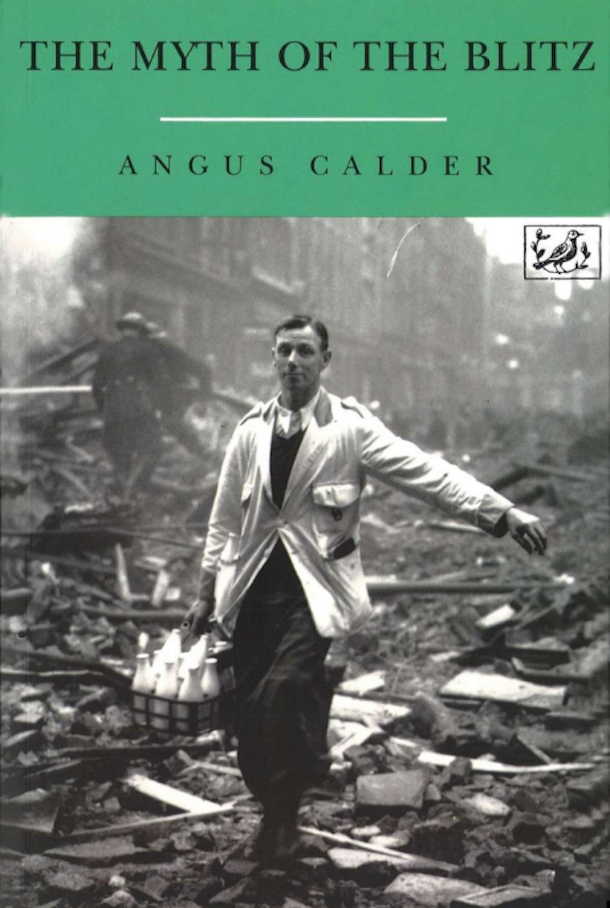

Book Review: ‘The Myth of the Blitz’

Since 1945, the contours of British collective memory have been shaped by a particular historical interpretation of the Second World War—one that gives prominence to the summer of 1940 as a transformative episode in British society. According to this narrative, perhaps most succinctly elucidated by Richard Titmuss in his 1950 book, Problems of Social Policy, 1940 was the point when the nation, divided by the class conflict and political in-fighting of the depression years, overcame its internal fractures and, united in defiance of German hegemony on the continent and daily bombing raids by the Luftwaffe, became the people. It is this orthodox view which the late Angus Calder sought to confront with the publication of The Myth of the Blitz in 1991.

Calder’s primary contention concerns the manner in which representations of the war in Britain—which he suggests are centred on the mythological triad of Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain and the Blitz—are predicated upon the acceptance and internalisation of wartime propaganda. In essence, the rhetorical oratory of Churchill, the Ministry of Information scripted radio broadcasts of Priestly and the staged cinematography of Jennings, have been used by academics, politicians and laymen alike as a factual guide to the realities of the war. This has led to a particularisation that has not only excluded marginal (and not so marginal) groups from the public discourse, but has also allowed for the totalising of a narrow, nostalgic and politically malleable collective memory of 1940 which reinforces a certain form of British identity.

At the time of the book’s release a questioning attitude towards the consensual memory of the war was not, at least in historiographical terms, unique. The People’s War, published by Calder in 1969, had already navigated this path, as had Clive Ponting’s 1940: Myth and Reality. In a sense, the quantitative empiricism of The Myth of the Blitz can be seen as a continuation of a wider trend of European revisionism which emerged in the 1960s, concerned as it was with renegotiating the realities of the Second World War. Calder’s most noteworthy addition to the field, then, was to highlight how memory evolves and is appropriated to define national identity and give meaning to contemporary situations.

Indeed, the content and context of the ‘myth’ are inextricably linked. The book began to take form in the early 1980s, a period of heightened class antagonism and political polarisation, which saw the myth of 1940 being invoked by both sides of the divide to confer legitimacy upon their respective viewpoints. Calder is clear that the continuous politicisation of Britain’s wartime experience and the ubiquitous position of the ‘myth’ in public life provided the principal impetus behind his decision to write the book, and this is evident in its focus on the continuation of acute social cleavages in Britain throughout the war. As he explains, “my anger over the sentimentalisation of 1940 by Labour apologists, then over the abuse of ‘Churchillism’ by Mrs. Thatcher during the Falklands War, led me to seek, every which way, to undermine the credibility of the mythical narrative.”

This has two wider consequences for understanding the development of collective memory. Firstly, it demonstrates how the contested nature of the war’s meaning allows it to be appealed to in order to justify often diametrically opposed political visions. Second, it shows how a change in, or a challenge to, collective memory can be brought about by events and structural factors seemingly extraneous to the subject at hand.

Calder’s adherence to a revisionist framework is also apparent in the organisational layout of The Myth of the Blitz. The book is divided into eleven chapters, each of which analyses a different social or cultural aspect of the war and remembering in general. Along with the impressive range and typology of sources which are drawn upon—from Mass Observation to scholarly works, and government documents to personal diaries—this introduces a degree of multiplicity that successfully conveys the complexities of wartime memory. For instance, the juxtaposition of the supposedly unique British reaction to strategic bombing with parallel German and Italian responses has important implications for the link between collective memory and national identity. In addition to blurring the lines between perpetrator and victim, foreshadowing developments in German revisionist literature, Calder convincingly argues that if the distinctiveness of national memory is weakened its solidity and significance will also be diluted. For the most part this is not controversial in and of itself. However, it has repercussions for the widely held belief that Britons would have uniformly resisted German occupation. It is arguable that such a challenge to the core underpinnings of British self-image would have as radical an impact today as it did in 1991.

In spite of the substantial contributions made by The Myth of the Blitz to the debates around identity, memory, and the cultural significance of the Second World War, Calder’s approach to the subject is not devoid of limitations. Any author who explicitly wishes to deconstruct orthodox historiography risks, by focussing specifically on the invisible constituents of the public discourse, replacing an established myth with an equally caricatured and inaccurate counter-myth. The growth of Plaid Cymru and increased juvenile delinquency during the war, to name but two examples, remain on the periphery of collective memory for rather mundane reasons—namely, their exceptional or un-noteworthy nature. To his credit, Calder engages with the conventional scholarship on 1940, acknowledging that the dominant British view of the ‘finest hour’ would not persist were it not grounded in a reality to which a broad cross-section of society could relate. Somewhat ironically, therefore, the overriding flaw of the book is that, in emphasising the degree of social and political tension which existed throughout the war, it makes Britain’s eventual success in the face of inauspicious circumstances appear even more incredible. Calder only mentions this dialectic briefly, and when he does it seems to confuse the book’s intended narrative.

Nevertheless, The Myth of the Blitz remains an important milestone in the critical analysis of the memory of the Second World War in Britain. Its nuanced treatment of various complex and inter-related topics, and its informative examination of the origins and uses of popular memory, set it apart from other more polemical texts. Although it is questionable as to whether Calder’s literary intervention had much of an impact on prevailing political and social attitudes, it did play a central role in laying the foundations for further revisionism in academia and the media.