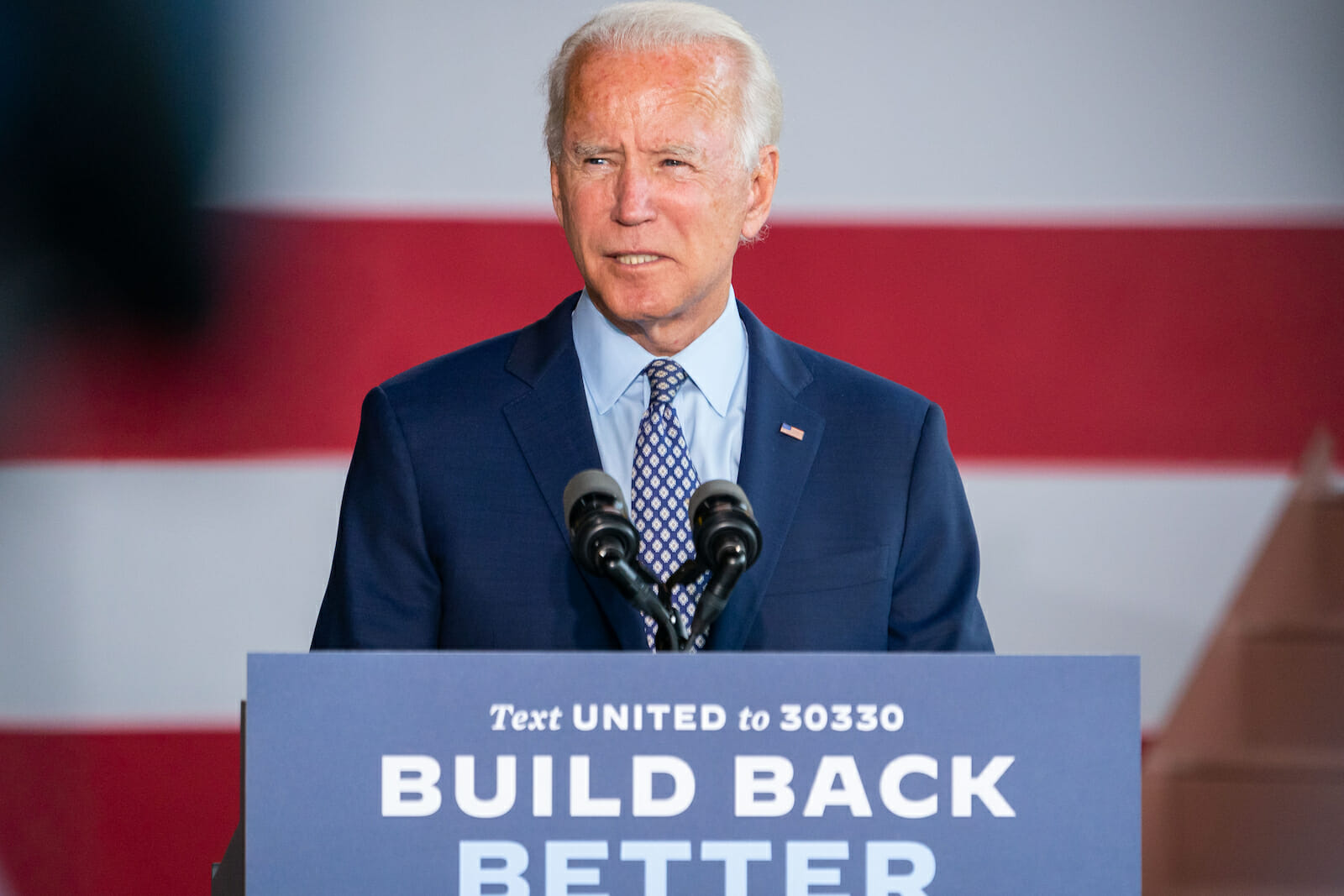

Can Biden’s Build Back Better World Compete with China?

Leaders of the Group of Seven ended the three-day summit with a joint statement urging China to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms. At the heart of the summit, was a new initiative to support global infrastructure investment, insinuating a better alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While details of the Build Back Better World (B3W) were sparse in the G7 communiqué; the Biden White House issued a fact sheet emphasising strong strategic partnerships, good governance, and value-driven principles.

President Biden’s launch of the initiative embodies an idea that has existed among analysts for a while. Skepticism of the BRI is not new and has garnered criticism just as much as it has gained enthusiasm. The lack of transparency coupled with the reputation of being an instrument for debt traps have been primary drivers for the BRI’s significant pullback in recent years. In underscoring these challenges, it has paved the way for G7 countries to provide a competing alternative to China’s ambitious BRI.

With the overall trend of more countries participating in the BRI; the United States’ apprehensions have loomed large in recent years. Competing initiatives by the U.S. have not materialised into tangible projects; but initiatives by Japan, India, and European Union countries have gathered steam, reflecting the need for a better alternative to the Belt and Road Initiative. In 2019, Japan won endorsements by G20 leaders to a set of Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment. In the same year, the EU and Japan announced the Partnership on Sustainable Connectivity and Quality Infrastructure, and in January, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on a global EU Connectivity Strategy which is an extension of the EU-Asia Connectivity Strategy.

Efforts by like-minded countries underpin common concerns regarding Beijing’s intentions with the BRI and expanding Chinese territorial control. Bearing in mind such realities, the U.S. has progressively understood the need to provide a positive option to countries, as seen by efforts like the Blue Dot Network launched in 2019 with Japan and Australia. While these endeavours have been viewed in a positive light, they have been slow to gain traction.

The Build Back Better World with G7 countries may be a positive development, but the economies of the member countries are still trying to recover completely from the financial crisis triggered by the pandemic. The UK making cuts to its foreign aid budget illustrates the rough years it has been facing and raises concerns on the ability to acquire enough capital to keep the B3W afloat. Infrastructure projects being at the forefront of the B3W will demand private capital from member countries; however, these countries have sought and are still seeking Chinese capital to revamp old infrastructural systems. This further adds to the complexity of the situation that may cause teething problems as talks on achieving tangible goals start cropping up.

With these difficulties, the B3W will start off as a modest attempt to counter the BRI. In due course, this may result in delayed projects much like China dragging its feet on the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The U.S. and its G7 partners will have to learn lessons from China’s missteps so that it does not meet a similar fate. Evidence of failure is visible in debt renegotiations; where Sri Lanka has given up control of Hambantota Port and Pakistan is negotiating to get easier terms from Beijing on the CPEC. Washington and its partners need to take such instances as cautionary tales in order to make it a success. Nevertheless, the B3W has the potential to foil the BRI in the long run if it stays committed to smaller pilot projects and gradually allures other countries that have existing apprehensions of the BRI.

Considering the loans that China has extended to these nations and its leverage over domestic policy decisions when debts are not repaid, the trust deficit between Beijing and BRI countries will increase, which can serve as an effective tool for B3W to create a framework with realistic loans and lending policies.

The manifestation of the B3W will hinge on various nuts and bolts that the U.S. should be prepared for. The Biden administration will have its work cut out in building a narrative as a strategic manoeuvre that can benefit developing countries. It is a chance for democracies to position themselves as reliable stakeholders in global leadership. The B3W is more than just a developmental tool; it is a strategic narrative about whether the West can respond to China’s influence. It is not difficult to rationalise the Biden administration’s call to launch such a project. Beyond infrastructure, the U.S. and China are involved in a battle of narratives.

The current administration’s initiative reveals Joe Biden’s inclination to work with like-minded partners and will have to lay the groundwork for a sustainable and concrete plan. At the helm of it, the first set of projects will be crucial in setting the tone for how the B3W will pan out in the future; and if it succeeds only then can it deliver the six core characteristics of the B3W.