Changing the U.S. Aid Culture Toward Egypt: A Political ‘Hook,’ or a Humanitarian ‘Cord’?

U.S. aid to Egypt has always been a controversial topic. Egypt consistently scores poorly on the World Economic Global Gender Gap Report ranking (136) out of the (145) countries listed for the year (2015). Egypt’s recent actions against Human Rights NGOs documented in Case No. (173) which urges conducting a thorough analysis of the country’s behavior against NGOs, human rights, and to seeks to explore the purposes and policies of the U.S. aid programs in Egypt to better serve democracy through the aid program regulations.

A better understanding of U.S. foreign policy in Egypt can be a tangible opportunity to improve the effectiveness of aid programs through unfolding the paradoxical relationships between the aid program representation and democracy in Egypt.

American Foreign Policy with its aid program has not had a great positive impact in Egypt. The government resistance to cooperating with funded projects to track the improvement or highlight the factors of improvement has been huge.

In the report titled: “Everything You Need to Know about 2015 U.S. Aid to Egypt,” the Advocacy Director at Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy TIMEP, Colleen Costello confirms that: “According to official statistics, about half of all Egyptians live near or below the poverty line. Unemployment and under-employment remain high, by some accounts reaching as much as (30) percent among university-educated youth. One of the U.S. AID Funding Conditions is that “the Secretary must…certify that Egypt is meeting seven aid conditions related to the promotion of democracy and protection of human rights…If those human rights conditions are certified, up to $725,850,000 of the aid to Egypt may be released. Up to an additional $725,850,000 may be released if, 180 or more days after the first certification, the Secretary avers to Congress that the human rights conditions continue to be met.”

In a (2014) report issued by CAPMAS (Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics) the unemployment rate for women in Egypt was more than double that for men: women’s unemployment reached 24% in 2013, compared with 9.8% for men.

Costello illustrates how the education system suffers from low quality and does not produce enough skilled and qualified workers to meet employers’ needs: “A large portion of the economy remains informal, with low wages and little job security or benefits (and no contribution of tax revenue to the state). Egypt’s infrastructure and public services are straining under the weight of its growing population; in just one example, only (15) percent of villages are connected to sanitary sewage lines. More than (20) percent of children under age five suffer from stunted growth caused by inadequate nutrition. Affordable housing remains so hard to come by in many parts of Egypt that many Egyptians are not able to marry until well into their thirties. Inequality has increased in recent decades. According to a recent global wealth survey, the number of Egyptians belonging to the middle-class and higher-income categories has been cut almost by half over the past 15 years, from 5.7 million to 2.9 million people. Those who are considered middleclass or above constitute just 5.4 percent of the population, but own two-thirds of the country’s wealth.”

While many political analysts do not doubt the desire of the USA to improve Human Rights conditions in Egypt, nor the desire of the Egyptian government to end terrorism and defeat the Islamic State in Sinai, Senior Fellow for Middle Eastern Studies, Council on Foreign Relations, Elliott Abrams, believes that the United States assistance for Egypt must be modulated as Egypt’s tactics on the security levels appear to be failing.

“There is a remarkable similarity between the structure of US aid to Egypt, and the structure of the Egyptian military. Both were established decades ago, and both badly need rethinking and upgrading,” Abrams said in his testimony before the Senate Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs on April 25, 2017. He also confirmed that the military assistance program “is pretty much irrelevant to the effort to combat terror in Egypt. The Egyptian military has, as I’ve noted, wanted to spend vast sums on submarines and frigates and higher performance combat jets, all of which are useless in fighting terror and waste scarce resources.”

A Political Honeymoon!

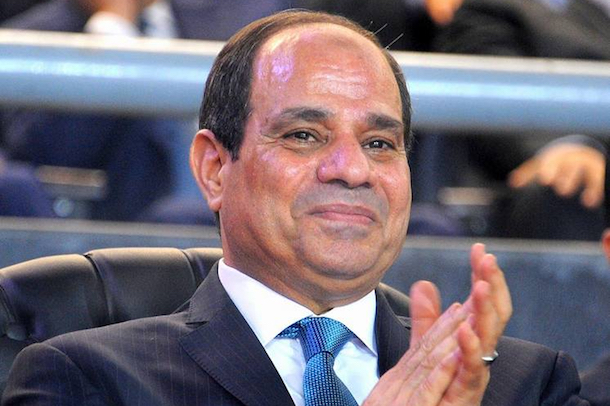

An indicator of a clear shift in U.S. foreign policy toward Egypt was marked by the warm welcome President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi of Egypt received from President Trump at the White House last April 2017. Dual remarks of mutual understanding were expressed. Trump stated that Egypt has “a great friend and ally in the United States.” El-Sisi replied that “You will find Egypt and myself always beside you…in the counterterrorism efforts.

The remarks seem to be ushering in a new era of mutual political bargaining. Days later, Aya Hijazi, an Egyptian American social activist released from jail in Egypt after nearly three years of detention with false accusations relevant to establishing and running a foundation to help educate street children, visited the White House. Did the new era of ‘mutual’ understating between the two regimes indicate that there will be policies that will strengthen human rights and economic prosperity in Egypt?

Beyond Human Rights Concerns: a Perplexing Disconnect!

The answer to the former question was not positive at least for Egypt; the mechanisms for reforms in Egypt have taken a different direction. The recent U.S. aid cuts totaled $290.7 million over human rights concerns in Egypt mark how the earlier warm fundamental shift in American foreign policy is raising a lingering question; Will the USA be able to shoulder its global responsibility to correct human rights and economic conditions in Egypt?

According to the Human Rights Watch, human rights conditions in Egypt have been deteriorating since 2011 and the United States did not cut its aid to Egypt at that time. Is it timing, human rights, or a political issue now? The answer has been provided by Elliot Abraham stating that “Egypt’s weight in the region has simply declined.” Yet, with the shutdown of Human Rights NGOs, and illegally arresting human rights activists, it is reasonable that the effectiveness of the aid program is in fact questionable.

Analyzing the latest aid changes and questioning whether they really target Egypt’s recent policies against Human Rights NGOs and social activists is very controversial. In his letter to President Trump, SASC Chairman John McCain urges President Trump to keep pressure on Egypt over Human Rights violations: “As you continue to work with the Government of Egypt on its human rights agenda, I urge you to raise the issue of the continued imprisonment in Egypt of nearly 20 American citizens, including college student and New York native Ahmed Etiwy. Mr. Etiwy has been falsely accused of participating in unauthorized protests, despite exculpatory evidence obtained by his lawyer, and is being charged in a mass tribunal with 493 codefendants. His imprisonment seems to be part of a troubling crackdown on independent voices across Egypt over the past several years, and he has now languished in pretrial detention for over four years. The trial is schedule to be adjudicated on August 28, 2017, making this case especially urgent.”

There are fears that Egypt will be a “jihadi factory,” together with the weak “security situation,” the “killing of civilians,” along poor “prison conditions,” with “60,000 political prisoners.” Abraham clearly attributed The United States aid to Egypt to how ‘important’ was Egypt’s’ role in the Middle East and to The United States. For example, at the time that Egypt was important to the Israeli-Palestinian peace process when “Mr. Carter, Mr. Sadat and Mr. Begin met at Camp David, Md., for 13 days” to sign the Peace Treaty. “Since then the average amount of aid, in total, has been around $2 billion per year, of which 1.3 billion has been military aid since the late 1980s,” Abraham stated.

All these factors make the recent aid cuts go far beyond the concerns over Human Rights purposes. Overall it is Egypt’s political diminished influence that makes the human rights purpose seems relevant to denying the funds. For Egypt, the answer needs to be more than ‘regretting the decision” of the Trump administration to deny the aid. The situation needs tangible and realistic commitment to improving economic, political, and human rights conditions. I am quoting Abraham’s words on the real purposes of the aid for Egypt as a final reminder. The aid is “to help achieve a stable, secure Egypt that can defeat the terrorist threat it faces and protect its borders, help to stabilize the region, remain at peace with Israel, and protect the freedom and human rights of Egyptians.”

My observation will end with Tom Lantos’ question: “Tell me, really, do you think Egypt needs more tanks, or more schools?”