China’s Zero Sum Vision of the World

The emergence of a new global power has often profoundly shifted the geopolitical landscape and caused considerable discomfort among the established order. China’s economic and political resurgence is doing that, but apart from the inevitable uncertainty and tension associated with any shift in global power, much of the angst in China’s case stems from its failure to engage in behavior concomitant with its increased global responsibilities – or even to acknowledge an obligation to do so.

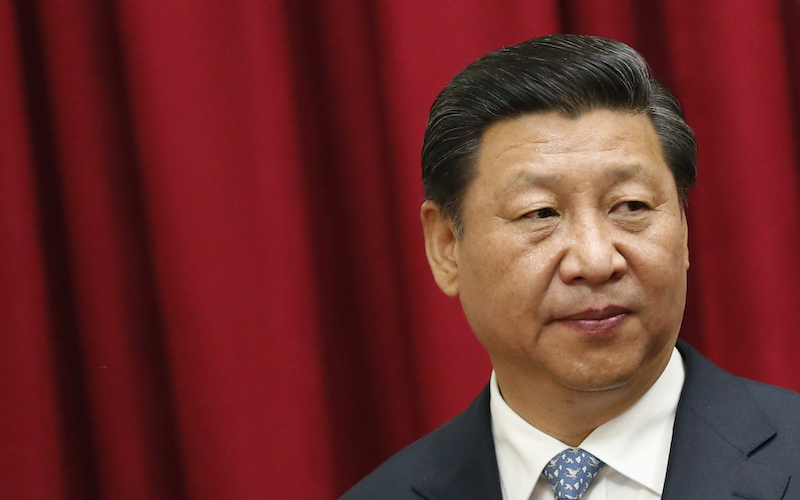

China has ascended rapidly onto the global stage by virtue of its economic might, even as it retains characteristics of a developing country by GDP per capita. China seems to want it both ways – it plays geopolitical power games as a force to be reckoned with among equals, yet declines to shoulder the burdens of a great power, or even demands that it be afforded the benefits ordinarily due to an underdeveloped charity case. In this regard, China’s leadership simultaneously nurses a profound grievance against “colonialists” and “aggressors” as it expands its direct political and economic influence across the globe. China’s leaders show bravado when on the world stage, but seem deeply paranoid that their rule at home could all fall apart at any time.

While China’s public pronouncements may at times appear mercurial, they are part of a well-conceived strategy. On one hand, China seeks to leverage benefits consistent with being a developing country, plays upon the west’s historical guilt over colonialism, and exploits the west’s continued belief that economic development will inexorably lead to pluralism. On the other hand, it does not hesitate to attempt to parlay its growing power into influence whenever and wherever it can. This Janus-like strategy gives China leeway and flexibility in crafting its international political and economic policy.

At home, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has established Socialism with Chinese characteristics, or, less euphemistically, state capitalism, that necessitates state powers using markets to create wealth, while ensuring political survival of the ruling class. As a government that now presides over the second largest (soon to be the largest) economy in the world — and one that depends intimately on flows of international goods and capital — the CCP no longer simply practices state capitalism at home: it applies it globally.

Although the west has long played mercantilist games, it has gradually migrated toward the belief that liberalization of international markets is mutually beneficial for all countries. But China continues to see international economics as a zero sum game. It finds its developing status a convenient cloak and justification for the application of global state capitalism. It engages in beggar-thy-neighbor policies it deems advantageous, and distorts the world’s markets according to the dictates of its political demands, while dismissing criticism of such behavior as unfair to a developing country. Similarly, on political issues, China portrays naked self interest as the reasonable demands of a developing country, and displays this behavior in nearly every arena in which it interacts with the world, from foreign aid and investment to multilateral institutions to international relations.

The deliberate undervaluation of the yuan in the last decade pointed to further distortions of international markets by China’s state capitalism. The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimated that the yuan was undervalued by between 20 and 40 percent, amounting to a massive export subsidy. However, the yuan’s undervaluation was just the tip of the iceberg. As importantly, Chinese banks receive a hidden subsidy: a wide spread between the rates paid on household deposits and the rates banks charge for loans. Bankers, who are in effect state employees — given that the banking system is largely government run — funnel the artificially cheap money to state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Since households have no investment alternative to domestic banks, they in effect provide a huge subsidy to Chinese industry. The CCP’s state capitalism mandates growth and employment through exports and investment at all costs in order to ensure its political supremacy.

Even as China increases its economic presence through investment and greater influence in multilateral institutions, it continues to reap benefits intended to accrue to the world’s truly needy nations. By all rights, China should be a donor nation in multilateral development banks, not a recipient of aid. That China is the Asian Development Bank’s largest recipient of Bank funds really is scandalous, and comes at the cost of countries like Bangladesh and Nepal, the poorest of the poor, which truly need the resources. As of 2007, China was ranked in the top 15 of development aid recipients worldwide. By 2010, China had increased its number of voting shares in the World Bank to become the third largest stakeholder, behind the U.S. and Japan. The U.S. and Japan do not receive development assistance from organizations like the World Bank – at what point does China’s absolute strength count for more than its per capita development? And why should donor countries like the U.S. and Japan allow this double standard to occur?

Politically, China is an irredentist power that arguably has done more to advance global nuclear proliferation than any other state save Pakistan, while routinely doing business with some of the world’s worst governments. Apart from the issues of Taiwan and the Spratly Islands, China lays claim to much of India’s state of Arunachal Pradesh, and caused major jitters in 2009 with incursions into the territory combined with strident rhetoric. It has blocked Asian Development Bank projects approved for India over the issue. It helped Pakistan develop its nuclear arsenal and ballistic missile technology. The largest recipients of Chinese military aid have in the past been India’s neighbors, including Myanmar, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka in addition to Pakistan; India fears that China is engaged in a concerted campaign to undermine and contain it. In addition, China continues developing its “string of pearls” strategy in the Indian Ocean, investing significant resources to develop deep water ports in the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and the Seychelles. These appear to be a basis for the projection of a powerful naval presence into what India considers its backyard.

Meanwhile, China blocks action against or actively supports a rogue’s gallery of nations, among them Iran, North Korea, Sudan, and Zimbabwe. It claims it has no influence over their actions, based on its policy of non-interference, but China’s support clearly requires a quid pro quo, be it natural resource wealth, business ties, or a geopolitically strategic use. China has avoided sanctions from the international community, partly due to the image it has cultivated of itself as a non-interfering developing country. While the West has also projected its power and dealt with equally noxious states, domestic political constraints make such “deals with the devil” increasingly difficult to sell to electorates attuned to human rights, ethics, and governance, and who are provided with the freedom of speech to object to their governments’ actions. No such freedom exists in China.

As long as the CCP continues to govern, China will not change. It will continue to comport itself according to its zero sum vision of the world. At best, the West can hope the CCP’s interests converge toward those of the larger globalized world. Even as China speaks of a peaceful rise within the existing international structure, its behavior, which at times may be described as impertinent, belies the West’s desire to have faith in its words. Indeed, many nations around the world appear to be running out of patience at China’s uncompromising approach to the promotion of its own self interest. President Obama has attempted to engage China on a variety of global issues, and for the most part found that his proffered hand was met with a clenched fist. With either Mr. Trump or Mrs. Clinton in the White House starting in January, the U.S. is likely to soon discard the illusion that China is gradually transitioning to become a responsible global power.