COVID-19’s Impact on China’s Global Trade and Investment Regime

China’s economic juggernaut has been brought to its knees by COVID-19. In the first two months of this year, Beijing reported a 17% drop in exports (including a 28% drop in exports to the U.S.), a 4% drop in imports, and a trade deficit of $7.1 billion. For the Chinese government to publish such data, things really must be bad, and we can assume that the data is actually worse than is being reported. This raises serious questions about whether the global trade and investment regime Beijing has crafted over the past three decades – in which the world became dependent upon China as its trading and manufacturing epicenter – will be sustainable going forward.

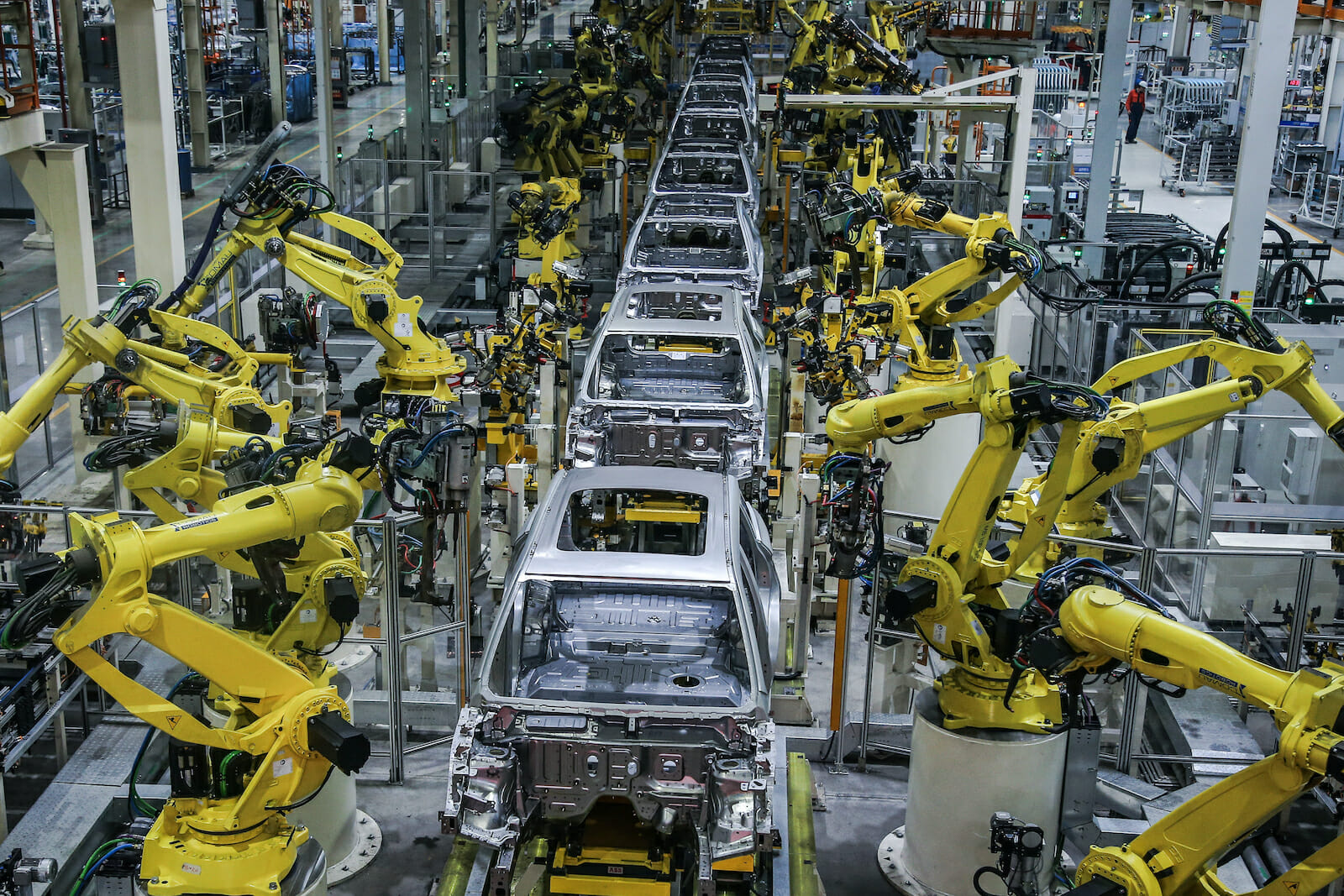

A decade ago, China had already established itself as having near-monopoly status on the manufacture of a whole range of products the world rapidly consumes. By 2011, 91% of all personal computers, 80% of all air conditioners, 74% of global solar cells, 71% of cell phones, and 60% of all cement were manufactured in China. Today, the world’s largest 1,000 companies (or their suppliers) own more than 12,000 factories, warehouses, and other facilities in COVID-19-quarantined areas of China, which means that they cannot operate these facilities and must find alternative means of supplying their businesses.

Some of these companies will have backup suppliers outside of China, but many do not, and many of those that do have backups will not have been incident-ready to seamlessly transition to an alternative supply chain. What the virus has made abundantly clear, by virtue of how quickly national and global economies have essentially shut down in short order, is that business interruption planning has largely been inadequate on local, national, and global bases. Even the multilateral organization charged with ensuring global health – the World Health Organization – has provided a lackluster response to the virus.

Despite being on business and government crisis planning radars for at least two decades now, plenty of organizations around the world have either not paid sufficient attention to pandemic planning, having apparently presumed that such a scenario would ultimately become someone else’s problem. Now, of course, it is too late to do something about it. But beyond that, COVID-19 is forcing many businesses to question the premise upon which they based their decision to so closely embrace China. When times were good, they profited handsomely; now the reverse is true.

It was never really a smart idea to devote so many critical resources to a single source (China). Having done so, many firms became blinded by their decision, perhaps recognizing too late that it could take a decade to become profitable in China, if they were to become profitable at all by operating there, given Beijing’s draconian approach to foreign trader and investor management. Many of them endured operational restrictions in China that they would never have endured at another investment destination, by virtue of China’s population size and importance. Beijing knew this, and played them like a fiddle.

The compact made between Beijing and foreign businesses has all now come crashing down since China has, in essence, been closed for business for more than two months. At the very least, those businesses that were caught flat-footed will now ensure that they have alternative means of operation outside China, should they choose to continue to operate there. But many foreign businesses will now choose to either establish or enhance manufacturing operations outside of China. That may well change the very nature of how businesses think about China going forward, and with it, succeed in shifting global manufacturing toward multiple geographical “epicenters” of operation in the future.

Beijing has stolen enough intellectual property – from businesses and governments alike, and has the means to continue to do so regardless of whether businesses actually operate in China – that it may no longer matter to the Communist Party whether China remains the world’s manufacturing hub. That may actually fit neatly into the Party’s narrative that it become more self-reliant and consumer-focused. In the same vein, perhaps the world’s manufacturers will have come to the conclusion that operating in China is no longer an economic imperative, particularly given the plethora of geographical options – many of which are actually lower in cost – than China now provides.

There will undoubtedly be many unanticipated consequences of this viral outbreak, economically, politically, and from a global health response perspective. Surely, renewed emphasis on business continuity planning and questioning the basic premise upon which so many global businesses have continued to function will be among them.

This article first appeared in Fair Observer.