Dropped Investigations: Julian Assange, Sex and Sweden

Sex, the late Gore Vidal astutely observed, is politics, and not merely from the vantage point of those who wish to police it. In the case of whistleblowers, claims of aberrant, unlawful sex serves the purpose of diminishing credibility, tarring and feathering the individual and furnishing a distraction. Forget what was disclosed; focus, instead, on the moral character of the person in question. The rotter could not have been good anyway.

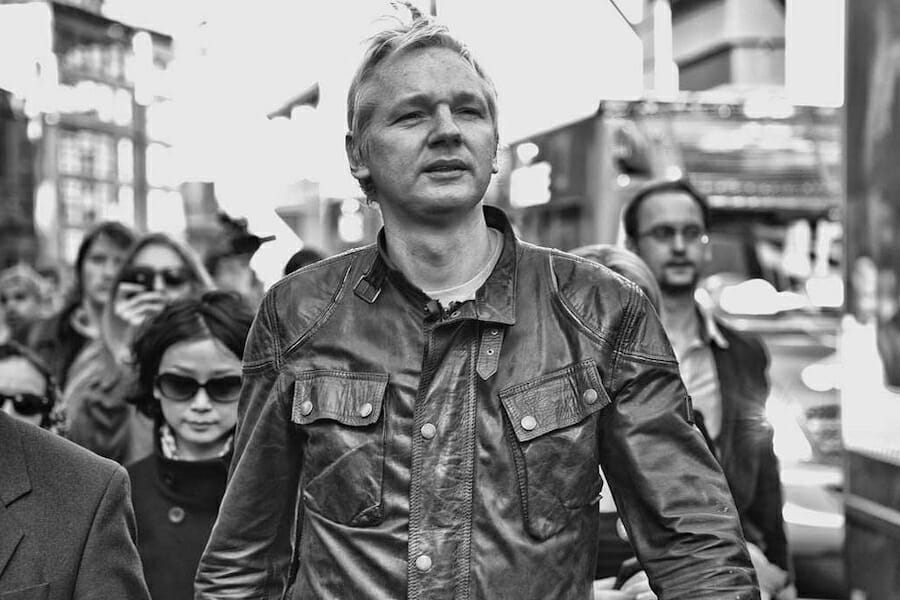

In the case of Julian Assange, the stench of accusation (never charge) of sexual assault clung stubbornly. “The road to Belmarsh and 175-years in prison was paved in Stockholm – and so it will be remembered,” tweeted the Defend Assange Campaign.

Then came the announcement from the Deputy Director of Public Prosecution Eva-Marie Persson: the Swedish investigation was being laid to rest. “The reason for this decision is that the evidence has weakened considerably due to the long period of time that has elapsed since the events in question.”

This did not mean Persson would let Assange off without a blemish on character. Some stain still had its place. “I would like to emphasise that the injured party has submitted a credible and reliable version of events. Her statements have been coherent, extensive and detailed; however, my overall assessment is that the evidential situation has been weakened to such an extent that there is no longer any reason to continue the investigation.” Despite no charge or trial, untested accounts are still being permitted to linger on the historical chronicle.

The effort to get at Assange via the sexual channel has been sporadic, arbitrary and inconsistent. In 2010, Assange was accused by two women of rape and sexual assault following a WikiLeaks conference in Stockholm. One of the women, Miss A (Anna Ardin), claimed that Assange had fiddled with a condom during sex. Miss W claimed to have been penetrated by Assange without a condom while asleep. The accusations were also supplemented by claims of unlawful coercion and molestation, though these had run their course by 2015.

The initial phase of prosecution lacked conviction. Stockholm’s chief prosecutor, Eva Finne, was unimpressed. She immediately canceled the arrest warrant claiming no “reason to suspect that he has committed rape.” Four days later, she dismissed the rape investigation. One of the accusers would also say that he had not been raped. But another chapter was being drafted. Claes Borgström, taking it upon himself to represent the two women, persuaded Marianne Ny seize the reins. The case was re-opened. All of this took place under the cloud of claims that US-Sweden intelligence sharing would be compromised if Assange was sheltered in Sweden, and the very pointed views of Sweden’s military intelligence service that WikiLeaks posed a threat to the country’s soldiers in Afghanistan under US command.

In 2017, the tired effort was shelved. With the storming of the Ecuadorean embassy in London and the forced eviction of Assange, prosecutors again got a burst of inspiration: the investigation was re-opened for a second time. The exercise seemed redundant, given that the United States would be having first dibs with its effort to extradite the publisher.

Over time, the sexual angle to the issue morphed into a crusade, becoming, intentionally or otherwise, a means to demonise the efforts of Assange and WikiLeaks. It aligned neatly, consistently, and even conspiratorially, with the recommendations of the US Army Counterintelligence Centre within the Counterintelligence Assessments Branch in its March 2008 document “Wikileaks.org – An Online Reference on Foreign Intelligence Services, Or Terrorist Groups?” As WikiLeaks relies on “trust as a centre of gravity by protecting the anonymity of the insiders, leakers or whistleblowers,” it was possible that “identification, exposure, termination of employment, criminal prosecution, legal action against current or former insiders, leakers, or whistleblowers could potentially damage or destroy this centre of gravity and deter others considering similar actions from using the Wikileaks.org Web site.”

Sexual misdemeanour was always going to be a formidable vehicle by which this could be executed. For Yana Walton of the Women’s Media Centre, the issue was condensed and simple: “Rape is rape is rape is rape, and should be prosecuted as such.” Such arguments ignored the defective processes behind the Swedish prosecution, the refusal to conduct interviews with Assange in the embassy, and the obsession with physically having him present in Sweden.

Beyond that was the point made by WikiLeaks, now gruesomely evident, that the United States would seek to have Assange delivered into its custody the moment he reached Swedish soil. Claims of sexual impropriety were subsequently sharpened to suggest that Assange was never a political prisoner in the embassy, let alone an agent of radical transparency.

In May this year, Caroline Orr’s less than considered scribbles parroted the US Department of Justice line that Assange “wasn’t a prisoner at all. He wasn’t being pursued for bravely standing up for truth; rather, he was hiding from it.” Very generous of Orr to know something others do not.

In suggesting her own understanding of the truth as unimpeachable, she proceeded to take a leaf out of the covert manual of whistleblower demonization, using misogyny as her preferred weapon. Being one naturally meant you could not speak, let alone shout truth, to power. “Assange is a misogynist who spent nearly seven years living in the Ecuadorean Embassy in London because he didn’t want to return to Sweden to answer to two women accusing him of sex crimes. Regardless of your feelings toward WikiLeaks, this is a major part of Assange’s legacy – and it matters.”

On his apprehension, British Labour MP Jess Phillips was appalled by the idea of women’s issues being “the political side salad, never the main event.” In responding to Assange’s arrest, “the political establishment slapped us around the face.” Speaking collectively as voice of the slapped, she found the debate about how best to deal with the Australian publisher one that ignored “the fact that Assange, for seven years, evaded accusations of sexual violence in Sweden.” Not a sliver of acknowledgment about Assange’s status of political asylum was made. Assange was merely a creep worthy of punishment.

Philips’s own tendency to trim the record was evident, ignoring the obvious point that the sex allegations (and not charges, as she mistakenly implies) were very much placed in the foreground to take discussions away from WikiLeaks and its disruptions. The bigger picture, which she dismisses as a case of “big boys playing toy soldiers,” was cluttered with the ongoing US investigation that finally confirmed its presence in April this year.

As with other figures with historical freight, Assange is a character flawed and troubled, hardly your card-carrying Women’s Libber or gallant knight. The ramshackle motor of history is not operated by saints; to even assume that level of purity and clean living suggests a degree of shuddering naïveté. But the stuttering Swedish prosecution, shelved then restarted, was never based purely on the dictates of conscience and the pursuit of justice on behalf of the claimed victims. Sex is politics, and from the start, the Assange prosecution, from Washington to Stockholm, was and remains, political.