Elbowed and Hustled: Australia’s Yellow Peril Problem

With the babble about Cold War paranoia becoming a routine matter in Canberra, the treacherous ground for war with China is being bedded down and readied. The Yellow Peril image never truly dissipated from Australia’s politics. It was crucial in framing the first act of the newly born Commonwealth in 1901: the Immigration Restriction Act. Even as China was being ravaged and savaged by foreign powers and implosion, there was a fear that somewhere along the line, a reckoning would come. Charles Henry Pearson, a professor of history at King’s College London, penned his National Life and Character: a Forecast (1893) with fear in mind. The expansion of the West into all parts of the globe and its claims to progress would soon have to face a new reality: the threat posed by the “Black and Yellow races.”

Pearson fastened on various developments. The population of China was booming. The Chinese diaspora, the same, making their presence felt in places such as Singapore. “The day will come and perhaps is not far distant, when the European observer will look round to see the globe girdled with a continuous zone of the black and yellow races, no longer too weak for aggression or under tutelage, but independent, or practically so, in government, monopolising the trade of their own regions, and circumscribing the industry of the Europeans.” Europeans would be “elbowed and hustled, and perhaps even thrust aside by peoples whom we looked down upon as servile and thought of as bound always to minister to our needs.”

The work’s effect was such as to have a future US President Theodore Roosevelt claim in a letter to Pearson that “all our men here in Washington…were greatly interested in what you said. In fact, I don’t suppose that any book recently, unless it is Mahan’s ‘Influence of Sea Power’ has excited anything like as much interest or has caused so many men to feel like they had to revise their mental estimates of facts.”

Anxiety, and sheer terror of China and the Chinese became part of the political furniture in Washington and in Britain’s dominions. In Australia, such views were fastened and bolted in the capital. The country’s first prime minister, Edmund Barton, drew upon Pearson’s work extensively in justifying the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901. The White Tribe had to be protected.

In 1966, the Australian historian Donald Horne noted the continuing sense of impermanence for those living on the island continent, that “feeling that one morning we shall wake up to find that we are no longer here.” He recalled the views of an unnamed friend about China’s political aspirations, voiced in 1954. By 1957, he predicted, Southeast Asia would have fallen to its soldiers. Australia would duly follow, becoming a dependency. “Because of the submerged theme of impermanence and even catastrophe in the Australian imagination,” observed Horne, “the idea of possible Chinese dominance is ‘believable’ to Australians.”

There was a hiatus from such feeling through the 1980s and 1990s. The view in Australia, as it was in the United States, was that China could be managed to forget history, disposing itself to making money and bringing its populace out of poverty. But historical amnesia failed to take hold in Beijing.

Australian current actions in stoking the fires of discord over China serve a dual purpose. There is a domestic, electoral dimension: external enemies are always useful, even if they are mere apparitions. Therein lies the spirit of Barton, the besieged White tribe fearing submergence. The other is to be found in the realm of foreign policy and military security. Australian strategists have never been entirely sure how far the ANZUS Treaty could be relied upon.

One moment of candour on what might happen to trigger ANZUS obligations took place in 2004. Australia’s Foreign Minister Alexander Downer, on a trip to Beijing, pondered the issue of how a security relationship with China might affect US-Australian ties. Asked by journalist Hamish McDonald whether Australia had a treaty obligation to assist the US in defending Taiwan, the minister stated that the treaty was “symbolic” and would only be “invoked in the event of one of our two countries, Australia or the United States, being attacked. So some other military activity elsewhere in the world, be it in Iraq or anywhere else for that matter does not automatically invoke the ANZUS Treaty.” Its provisions, he observed, had only been invoked once: when the United States was attacked on September 11, 2001.

This startlingly sound reading did not go down well. The press wondered if this cast doubt over “ANZUS loyalties.” The US Ambassador to Canberra John Thomas Schieffer leapt into action to clarify that there was an expectation that Australia muck in should the US commit forces to battle in the Pacific. “[T]reaty commitments are that we are to come to the aid of each other in the event of either of our territories are attacked, or if either of our interests are attacked, our home territories are attacked, or if either of our interests are attacked in the Pacific.” One cable from the Australian government attempted to pacify any fears about Australia’s reliability by suggesting that, “Some media reporting had taken elements [of Downer’s comments] out of context.”

The argument has now been turned. Discussion about Taiwan, and whether Australian blood would be shed over it, has much to do with keeping Washington focused on the Asia- and Indo-Pacific, finger on the trigger. If Canberra shouts loudly and foolishly enough that it will commit troops and weapons to a folly-ridden venture over Taiwan, Washington will be duly impressed to dig deeper in the region to contain Beijing. This betrays a naivety that comes with relying on strategic alliances with little reflection, forgetting that Washington will decide, in due course, what its own interests are.

So far, the Morrison government will be pleased with what the Biden administration has said. Australia could be assured of US support in its ongoing diplomatic wrangle Beijing. In the words of US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, “the United States will not leave Australia alone on the field, or maybe I should say alone on the pitch, in the face of economic coercion by China. That’s what allies do. We have each other’s backs so we can face threats and challenges from a position of collective strength.”

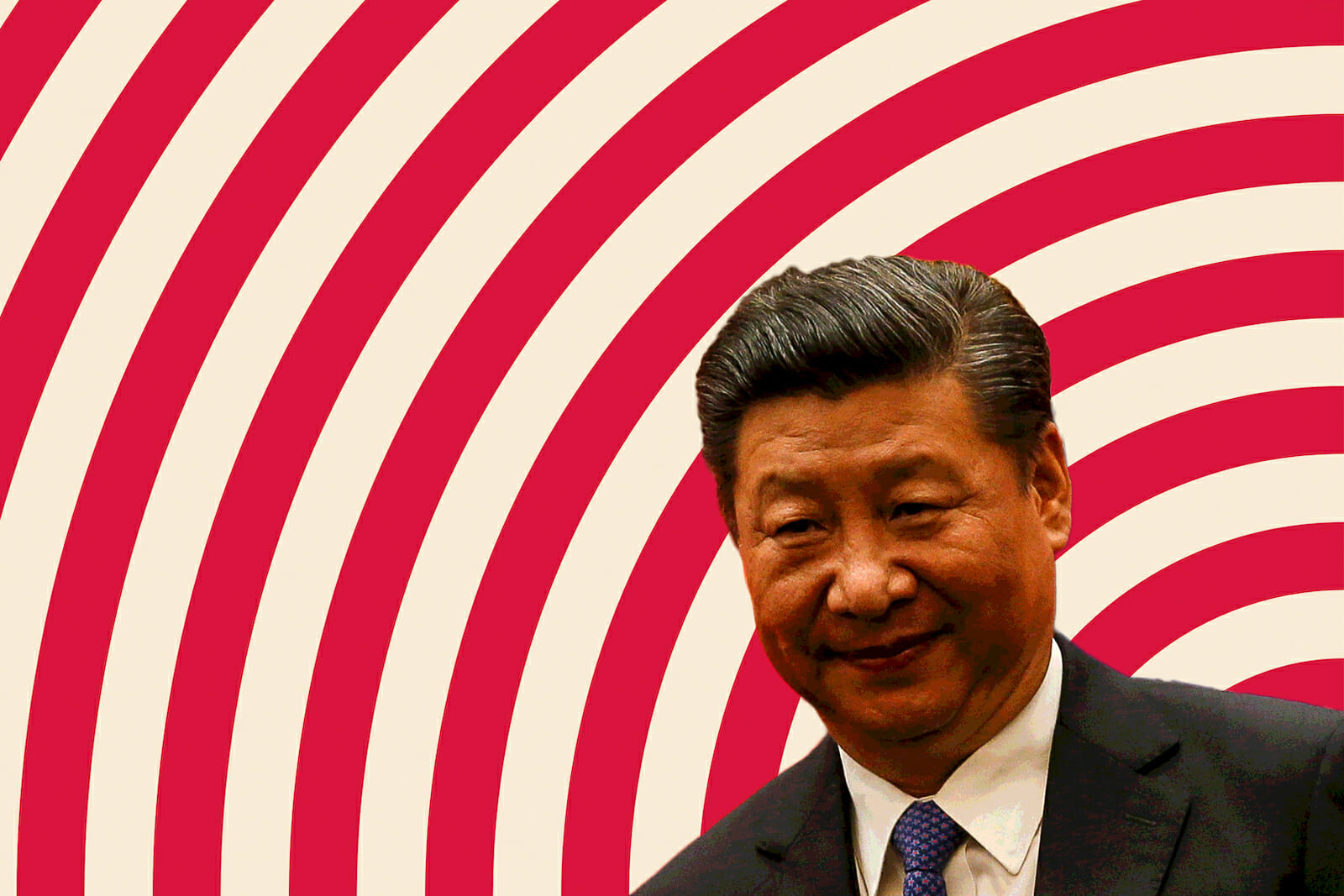

Australia’s anti-China rhetoric has its admirers. Michael Shoebridge of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute – a US security think tank in all but name – dismisses the value of words such as “major conflict,” preferring the substance of action. He talks about “honesty” about China, which is grand coming from a member of an outfit which is less than frank about its funding sources and motivations. That honesty, he assumes, entails blaming China for belligerence. “Reporting what [President] Xi says and what the PLA and other Chinese armed forces do is not ‘stoking the drums of war’; it’s noticing what is happening in our region that affects our security.”

Thankfully, former Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans is closer to the sane fringe in noting that words, in diplomacy, are bullets. He reminds us of the immortal wisdom of the 1930s Scottish labour leader Jimmy Maxton: “If you can’t ride two horses at once, you shouldn’t be in the bloody circus.”