European Soccer Duel: Proxy Battle Between Qatar and the UAE

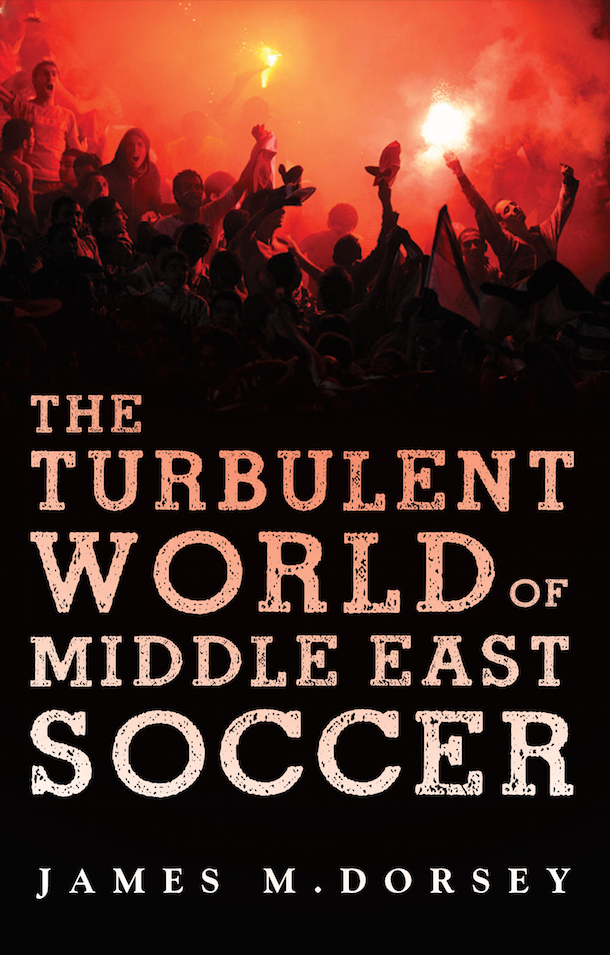

This week’s Champions League draw between Paris Saint-Germain FC (PSG) and Manchester City FC was more than just a battle between European soccer giants. It was a battle between Gulf rivals Qatar and the United Arab Emirates over differing visions of a transformed Arab world and competition for privileged status in the international community. It was also a struggle to counter criticism of large-scale human rights violations at times at the expense of one another.

The French-British soccer proxy battle may have ended in a draw, yet, the political battle between the two rivals, fought in part on the back of their European clubs, has largely left both sides licking their wounds even though Qatar and the UAE can also point to occasional points won.

High profile acquisitions of Manchester City by a senior member of the UAE ruling family and of PSG by Qatar fits into the two countries’ soft power strategy that aims to project them favorably on the international stage; garner empathy among the club’s huge global fan bases; and distract attention from the fact that both states are autocracies with poor human rights records.

Human rights in both countries has become an international focus as a result of their European acquisitions; the hosting of major events such as the 2020 World Cup in Dubai, 2022 World Cup in Qatar; and expected bids for other high profile sporting events like the Olympic Games. So has the two countries’ efforts to establish themselves as cultural and sports hubs in part by benefitting from association with brand names in sports as well as culture such as the Louvre in Paris, the Guggenheim in New York and the Tribeca Film Festival and education, including New York University, Georgetown University and Northwestern University.

Critics, including Human Rights Watch, have charged that the Gulf States’ affiliation with Western sporting and cultural brands amounts to reputation laundering. Speaking about the Western museums in Abu Dhabi author Kashnik Tharoor suggested recently that “their main aim is to dazzle and awe, to plump the reputation of Abu Dhabi and its rulers.”

Qatar and the UAE have responded differently to critics who have highlighted limitations on academic freedom and abominable labour conditions. Both have moved to improve labour conditions with the UAE acting more aggressively and comprehensively.

As a result, Qatar and its 2022 Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy that is tasked with preparing the World Cup was severely criticized last month by Amnesty International for not properly implementing measures to significantly improve workers’ living and working conditions. Qatar this week appointed an independent auditor to monitor implementation of improved labour standards in a bid to counter the criticism.

The move reflects the fact that Qatar in contrast to the UAE has engaged with its critics in trying to address their concerns. The UAE, by contrast, hired a private investigator, tasked with discrediting a New York Times reporter who had earlier this year reported on the country’s lack of academic freedom and on the condition of workers building a New York University campus in Abu Dhabi. A UAE-related human rights front in Norway, whose main task seemed to be praising the UAE’s human rights record and discrediting Qatar, was put last year under investigation on charges of money laundering. The UAE also spent millions of dollars to hire a US lobbying firm to plant pro-UAE and anti-Qatar stories in the media.

Relations between Qatar and the UAE have long been strained as a result of deep-seated and long-standing resentment by Emirati leaders of Qatar’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist groups. The UAE alongside Saudi Arabia and Bahrain withdrew its ambassador from Doha in March 2014. The ambassadors returned to their posts at the end of that year without Qatar making fundamental concessions.

While Qatar suffered a further public relations setback with the Amnesty International report and an earlier ultimatum by the International Labour Organization to shore up its act, the UAE has suffered equally damaging incidents. British national David Haigh, who became managing director of Leeds United FC on behalf of Bahrain’s controversial Gulf Finance House when it bought the club, asserted this week that he had been tortured in a Dubai prison after being arrested on charges of fraudulent financial dealings.

In perhaps an even more serious setback, the UAE’s differences with not only Qatar but with the Gulf’s behemoth, Saudi Arabia, were on public display when the Saudi-backed exiled president of Yemen, Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, earlier this month dismissed as vice president and prime minister Khaled Bahah, known for his close ties to the UAE, and appointed controversial General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, who is viewed as close to Yemen’s Islamist Islah party or Yemeni Congregation of Reform Party and the Muslim Brotherhood.

While Qatar’s identification with the World Cup has contrary to its expectations tarnished rather than boosted its image, partly as a result of poor Qatari communications, the UAE has succeeded in positioning Abu Dhabi’s soccer club-sponsoring Etihad Airways as one of its global top brands.

“Football is still the cheapest advertising there is if you want visibility… We spent $15m on the advertising for our Jennifer Aniston campaign and it was like a pea in the ocean. With Real Madrid we have 700 million people who love their club and the players. With Arsenal we have 500 million. We had no renewals last season and none this coming season, so we invested at a good time, I think,” said Boutros Boutros, senior vice president for corporate communications and marketing at Etihad’s major competitor, Dubai-based Emirates, another major sponsor of European clubs.

This week’s match between PSG and Manchester City proves Mr. Boutros’ point. The match, however, does not resolve Qatar and the UAE’s reputational issues nor does it camouflage their differences and proxy wars. Addressing systematic violations of human rights and unjustifiable working and living conditions of migrant labour could do the trick.