Culture

Four Enduring Myths of the Second World War

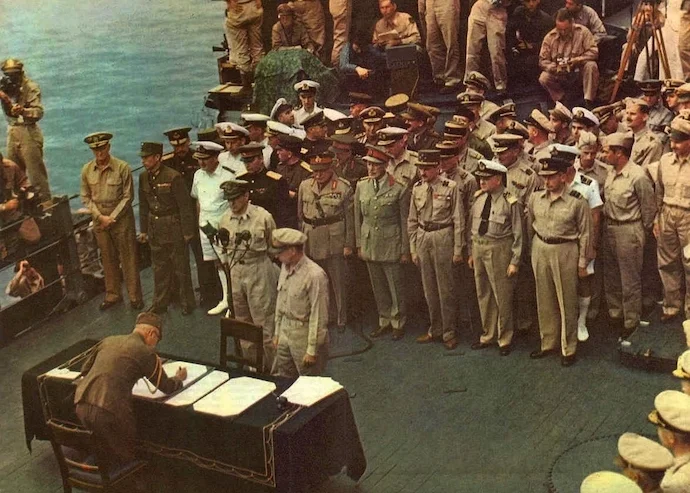

As the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War approaches, the essential roles played by China and Russia remain conspicuously overlooked in many Western narratives—just as they have been for decades. These two nations, whose contributions were critical to the defeat of fascism, are often marginalized or misrepresented in the prevailing accounts of the war.

This selective memory not only distorts public understanding of the past but continues to shape global political dynamics today. At the core of this distortion are four persistent myths that continue to influence perceptions of the Second World War.

1. The ‘Six-Year War’ Fallacy

One of the most persistent misconceptions is the narrowly defined six-year timeline of the war, which began with Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939. This view fails to account for the earlier acts of aggression committed by Japan, Italy, and others—actions that were critical to the eventual outbreak of full-scale global conflict.

Japan’s militarism began in 1931 with the invasion of Manchuria, and the Mukden Incident marked the start of its expansionist war in Asia. Renowned historians such as A.J.P. Taylor and John Toland have emphasized that Japan’s aggression in China was a pivotal precursor to the Pacific theater. Likewise, Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) signaled the rising tide of authoritarian violence that would engulf the globe.

These earlier events directly undermined the post–World War I international order and emboldened fascist regimes across Europe and Asia. The atrocities committed by Japanese forces in China—including mass executions, widespread sexual violence, and the devastation of cities like Nanjing—mirror the brutality of Nazi crimes against the Jews. In China, this era is remembered as the War of Resistance Against Japan, which lasted from 1931 to 1945—nearly a decade before the European conflict even began.

From the Chinese perspective, this was a long, arduous, and defining struggle that shaped the trajectory of the broader Allied victory—yet this perspective is almost entirely absent in Western accounts of the war.

2. The West-Centric View of the War

The dominant Western narrative continues to place Europe—particularly the Western Front—at the center of World War II. Landmark events like the D-Day landings in Normandy are frequently portrayed as decisive moments in the Allied victory, while the Soviet Union’s immense sacrifices and key strategic victories are often underplayed or disregarded.

This omission is not incidental. During the Cold War, downplaying the Soviet contribution served ideological and political purposes. However, the truth is inescapable: long before American or British boots hit the beaches of Normandy, the Soviet Union had inflicted catastrophic losses on the German military. The Eastern Front was the site of some of the largest and most decisive battles of the war, including Stalingrad and Kursk.

With approximately 27 million Soviet casualties, including both soldiers and civilians, the USSR bore the brunt of the war against Nazi Germany. The contribution of the Red Army was indispensable to the defeat of fascism in Europe, and the sheer scale of sacrifice demands greater recognition in any honest retelling of World War II.

3. China’s Overlooked Resistance

China’s role in the war remains underappreciated in Western historical accounts, yet its prolonged and tenacious resistance to Japan played a vital role in the eventual defeat of the Axis powers.

From 1931 onward, China was the primary battlefield of Japanese expansionism in Asia. The War of Resistance Against Japan continued until 1945 and resulted in more than 35 million Chinese casualties. Despite these staggering losses, China is too often depicted as a passive recipient of Allied aid or as a nation peripheral to the major theaters of conflict.

In reality, China’s military resistance tied down significant portions of the Japanese army, limiting Japan’s ability to deploy resources elsewhere in the Pacific. Chinese forces collaborated with the Allies in multiple campaigns, including along the Burma Road—a critical supply route that sustained Allied operations and diminished Japan’s overall strategic capacity.

China’s involvement was not simply symbolic. Its sustained resistance critically undermined Japan’s war effort and played a decisive role in shaping the course of the Pacific War. Yet this reality remains largely unacknowledged in many Western portrayals of the conflict.

4. Recasting Japan as a Victim

In Western popular memory, Japan’s role as an aggressor is often obscured by its postwar victimhood, particularly following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This narrative is especially troubling for many in China, where the memory of Japan’s wartime atrocities remains visceral and unresolved.

Japan’s imperial conquests were accompanied by brutal war crimes. The Nanjing Massacre alone, during which hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians were killed, raped, or tortured, is emblematic of the broader pattern of atrocities. And yet in the West, this history is frequently softened, contested, or omitted entirely.

In China, the failure of the Japanese government to fully acknowledge these crimes is a continuing source of national anger. Despite a vast archive of photographs, testimonies, and historical records, many Japanese officials have avoided issuing unequivocal apologies. The same pattern applies to issues like forced labor, the coercion of “comfort women,” and the destruction wrought by Japanese forces across Asia.

This reluctance to reckon with the past hampers regional reconciliation and feeds ongoing tensions in East Asia. The revisionism and denialism surrounding Japan’s wartime actions are viewed by many in China as a calculated attempt to rewrite history.

Toward a More Honest Memory

These four myths—regarding the war’s timeline, geography, and central participants—have deep roots in postwar politics. Cold War imperatives encouraged Western nations to emphasize their own roles while sidelining those of China and the Soviet Union. This historical framing continues to serve geopolitical purposes today, reinforcing existing power structures and narratives.

Yet, as global politics evolve, so too must our understanding of the past. Portraying Chinese efforts as merely nationalist propaganda or Soviet losses as peripheral not only distorts historical truth but also undermines efforts at international understanding and cooperation.

Correcting these misconceptions will require robust scholarly engagement across borders. Western historians must be willing to reevaluate long-held assumptions, incorporating a fuller understanding of the sacrifices made by all nations involved in the struggle against fascism.

The upcoming 80th anniversary provides a rare opportunity to broaden the public narrative—to recognize the global scope of the conflict, and to honor all those who paid the price for victory, not just those whose stories fit neatly into dominant Western frameworks.