How Does the American Public View Trade Issues With China?

In December of 2020, John Ratcliffe, the Trump administration’s National Intelligence Director, declared that China is the top threat to the U.S. and the free world. Ratcliffe said at the time, “Beijing intends to dominate the U.S. and the rest of the planet economically, militarily, and technologically.” However, it is unclear if China poses a more serious economic or military threat in the eyes of the American public. Economically, China has been accused by Washington of practicing unfair trade tactics, notably stealing American intellectual property. Despite President Trump’s initiation of a trade war in 2018, the public did not view it as a critical threat to the U.S., and a simulation model showed that China has more to lose from a trade war with the U.S.

In terms of U.S. security, China’s steady increase in military spending and discrepancies in reporting military expenditures causes concern that China’s rise to superpower status will not be peaceful. As a nuclear power, China’s passive approach to nuclear disarmament may signal the intentions of building up its nuclear arsenal or altering its pledge to forgo first-use strategies. Chinese assertiveness on claims in the South China Sea increasingly poses a security and economic threat to the U.S. and the region with the potential for military skirmishes with the U.S. Additionally, concerns about Chinese-sponsored cyber warfare fuel fears about American cybersecurity, given that the U.S. has claimed that state-owned enterprises in China have previously hijacked U.S. government programs.

While American experts recognize the economic and security threat China poses, a lingering question is if the American public agrees with their assessment. To assess the public’s consideration of the nature of China’s threat to the U.S., we surveyed 934 Americans recruited via mTurk Amazon on March 4, 2021.

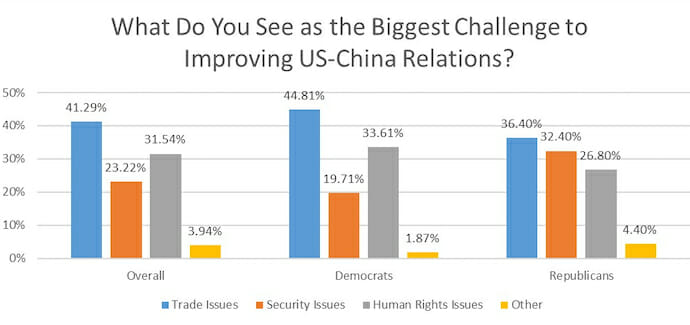

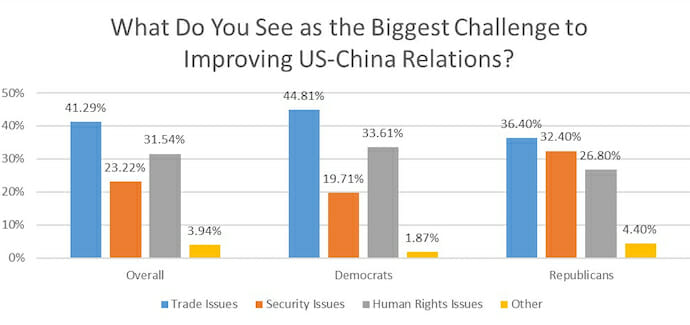

First, we asked respondents “What do you see as the biggest challenge to improving U.S.-China relations?” The options for responses were “Trade Issues,” “Security Issues,” “Human Rights Issues,” and “Other.” Of the 934 Americans surveyed, 41.29% of respondents chose “Trade Issues” as the biggest challenge to improving Sino-U.S. relations, 31.54% chose “Human Rights,” 23.22% chose “Security Issues,” and 3.94% chose “Other.” When broken down by party identification, we see Democrats as more likely to identify trade issues (44.81%), while nearly as many Republicans stated trade issues as security issues (36.40% vs. 32.40%).

Several factors may explain why a plurality of respondents overall chose trade issues as the biggest challenge to improving Sino-U.S. relations. First, Americans have a precedent of seeing China as a potential economic adversary. A 2015 Pew Research Center survey found that nearly 52% of respondents believed that “the U.S. trade deficit with China” was a “very serious” problem in the Sino-U.S. relationship, and 60% considered “the loss of U.S. jobs to China” as “very serious.” In addition, President Trump’s rhetoric around China heavily centered on economic relations and was a centerpiece of his campaign in 2016. The public may also simply underestimate the broader security concerns with China, although conservative politicians and media have addressed these issues more often. Scholars like Charles Glaser have debated the likelihood of direct military conflict with China in light of growing tensions between the two countries, suggesting reasons why post-Cold War countries often shy away from using direct military force. Lastly, with heightened media coverage of the internment camps for ethnic Uyghur Muslims and human rights issues more broadly, this may have overshadowed perceived Chinese military aggression.

Several factors may explain why a plurality of respondents overall chose trade issues as the biggest challenge to improving Sino-U.S. relations. First, Americans have a precedent of seeing China as a potential economic adversary. A 2015 Pew Research Center survey found that nearly 52% of respondents believed that “the U.S. trade deficit with China” was a “very serious” problem in the Sino-U.S. relationship, and 60% considered “the loss of U.S. jobs to China” as “very serious.” In addition, President Trump’s rhetoric around China heavily centered on economic relations and was a centerpiece of his campaign in 2016. The public may also simply underestimate the broader security concerns with China, although conservative politicians and media have addressed these issues more often. Scholars like Charles Glaser have debated the likelihood of direct military conflict with China in light of growing tensions between the two countries, suggesting reasons why post-Cold War countries often shy away from using direct military force. Lastly, with heightened media coverage of the internment camps for ethnic Uyghur Muslims and human rights issues more broadly, this may have overshadowed perceived Chinese military aggression.

Next, we asked “Who do you believe benefits more from trade between the U.S. and China?” and 54.22% of those surveyed responded that “China benefits more,” 10.51% responded that “The U.S. benefits more,” and 35.27% responded that “The benefits are about equal.” Again, we broke this down by partisan identification, where clear differences emerge: Democrats were slightly more likely to claim benefits were about equal rather than benefiting China more (46.47% vs. 41.49%), while Republicans overwhelmingly viewed trade as benefiting China (72.80%).

The prevalence of China along with buzzwords such as “trade war” in U.S. media should be considered as a potential reason for our respondents’ answers, especially among Republicans. Once again, the variation in rhetoric between President Trump and President Biden regarding China are also possible explanations for our respondents’ attitudes about trade between the U.S. and China. Further reasoning may lie in the ongoing negative view of China, as a Pew Research Center survey found that Americans’ view of China has reached a fourteen-year low in light of trade tensions. Although the average U.S. citizen may not totally understand the specific details of hostile trading practices between the U.S. and China, the heightened exposure to all things China, whether economic or not, may influence how Americans view every issue with China.

The prevalence of China along with buzzwords such as “trade war” in U.S. media should be considered as a potential reason for our respondents’ answers, especially among Republicans. Once again, the variation in rhetoric between President Trump and President Biden regarding China are also possible explanations for our respondents’ attitudes about trade between the U.S. and China. Further reasoning may lie in the ongoing negative view of China, as a Pew Research Center survey found that Americans’ view of China has reached a fourteen-year low in light of trade tensions. Although the average U.S. citizen may not totally understand the specific details of hostile trading practices between the U.S. and China, the heightened exposure to all things China, whether economic or not, may influence how Americans view every issue with China.

The results of this survey provide a blueprint for U.S. policy priorities concerning China in the future. Since the public considers China more of an economic threat, we are likely to see discourse on economic relations dominate Sino-U.S. relations, even if trade wars decline. Although security threats are still of great interest to the American public, that trade issues are seen as a more pressing threat will likely continue to be reflected in Democrats and Republicans campaigning on being “hard on China.” Divergences in strategies will arise, yet overarching goals of reducing China’s economic power and “reducing interdependence” may be the same. The Wall Street Journal reported that candidate Joe Biden shared the Trump administration’s hardline stance on trade with China, indicating that relations will continue to be tense on account of lingering trade issues. Though security threats will continue to be a strain on Sino-U.S. relations, economic issues, specifically trade, will continue to direct both U.S. public opinion and U.S. foreign policy towards China.

The public’s perceptions regarding U.S.-China trade will need remedy if deeper economic ties with China are desired. One step to show how trade can be mutually beneficial would be to address how the trade war negatively impacted U.S. industries and consumers. Trade with China, though unbalanced, is more favorable than not trading with China. However, there is currently little incentive for China to change tactics. Since the U.S. gained little from the trade war, it is clear the U.S. cannot turn the tide of Chinese trade dominance alone. We are left with one question: how can the U.S. better relations with China when China is unwilling to yield on the greatest barrier to this relationship?