How Often do South Koreans Think about North Korea?

Outside observers tend to assume that South Koreans frequently think about their northern counterparts, but how accurate is this assumption? Existing research on South Korean public opinion on North Korea covers diverse issues, from those relevant to national security, such as the North Korean military and North Korea’s nuclear weapons, to broader issues about the North Korean people, with potential ramifications for reunification. Yet, little attention has been placed on how often South Koreans think about these issues. This underlying question has broad potential ramifications, especially in terms of understanding how concerned the general public is regarding North Korean bellicose rhetoric and actions.

Psychological research could provide insight into South Korean perceptions on North Korea. Media framing theory argues that the media’s reporting of an issue influences how people perceive the issue. North Korea is one of the most reported news issues in South Korea. Furthermore, South Korean newspapers often describe North Korea negatively, with terms such as “evil,” “enemy,” “poor,” or “despotic” potentially making people afraid and more likely to think about North Korea negatively. Similarly, media reports of North Korean missile tests and bellicose behavior could exacerbate anxiety among the South Korean public. An alternative explanation, desensitization theory, argues that consistent exposure to certain issues eliminates the emotional and behavioral response to those issues. North Korea is such an ever-present issue, with frequent missile tests and skirmishes, but rarely do these actions disrupt everyday life for most South Koreans and can be ignored.

More broadly, with economic, political, and generational shifts in South Korea, general interest in North Korea may be less than one would expect. For example, in a 2015 survey, only 56% of South Koreans were interested in the North Korean people and a 2017 post-election survey found that North Korea policy was not an important issue for voters.

To determine how often South Koreans think about North Korea, we surveyed 1,111 South Koreans from March 2-12 via a web survey, conducted by Macromill Embrain, using quota sampling by age, gender, and region based on census data. During the timeframe the survey was conducted, North Korea conducted two missile tests, which should have at least temporarily increased attention on North Korea. However, the dual challenges of responding to COVID and preparing for April’s legislative elections may have distracted South Korean attention away from their northern neighbor.

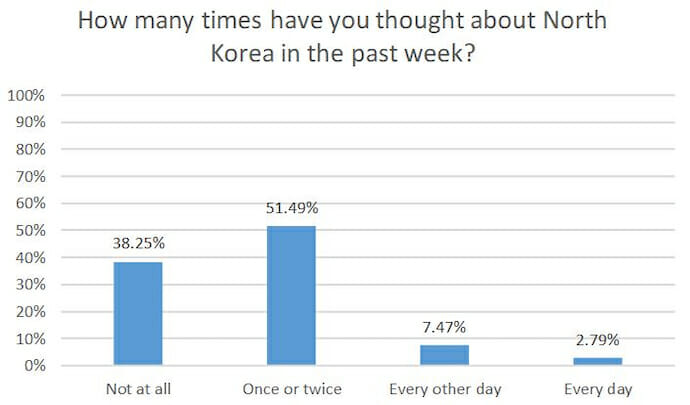

Respondents were asked “how many times have you thought about North Korea in the past week,” with four response options: “not at all,” “once or twice,” “every other day,” or “every day.”

Overall, the overwhelming majority of respondents either thought about North Korea not at all that week (38.25%) or thought about North Korea once or twice that week (51.49%). Conversely, approximately ten percent of respondents thought about North Korea every other day that week (7.47%) or every day that week (2.79%). The results strongly suggest that assumptions about South Korean attention to North Korea may be overstated.

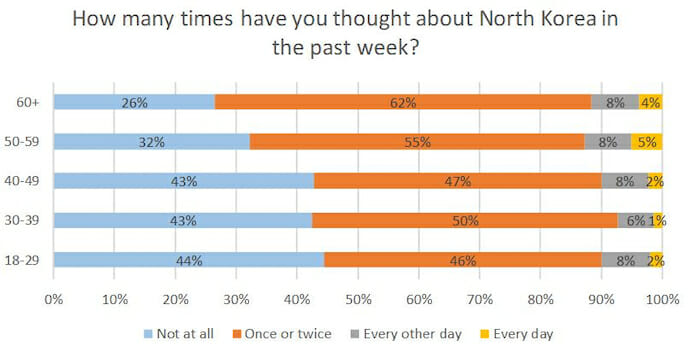

We further break down the data based on age and found stark differences (rounded to the nearest whole percent for clarity). Older respondents are more likely to remember the post-Korean War years of tense relations and the authoritarian era rhetoric that emphasized Korean brotherhood rather than the more recent democratic years. Older South Koreans might also have close family living in North Korea which prompts them to think about North Korea more often. According to our data, respondents who were 60+ and as well as those who were 50-59 thought about North Korea much more than their younger counterparts. Only 26% of respondents 60+ and 32% of respondents 50-59 did not think about North Korea that week while 4% of respondents 60+ and 5% of respondents 50-59 thought about North Korea every day. In contrast, younger respondents were approximately 10-20% more likely to not think about North Korea at all that week.

We further break down the data based on age and found stark differences (rounded to the nearest whole percent for clarity). Older respondents are more likely to remember the post-Korean War years of tense relations and the authoritarian era rhetoric that emphasized Korean brotherhood rather than the more recent democratic years. Older South Koreans might also have close family living in North Korea which prompts them to think about North Korea more often. According to our data, respondents who were 60+ and as well as those who were 50-59 thought about North Korea much more than their younger counterparts. Only 26% of respondents 60+ and 32% of respondents 50-59 did not think about North Korea that week while 4% of respondents 60+ and 5% of respondents 50-59 thought about North Korea every day. In contrast, younger respondents were approximately 10-20% more likely to not think about North Korea at all that week.

Regression analysis found similar results, that age positively corresponds with thinking about North Korea, even after controlling for basic demographic questions such as gender, education, income, ideology, and religion (Buddhism, Protestantism, and Catholicism). In fact, the only variable to have a stronger positive effect on thinking about North Korea was personally knowing someone who moved from North Korea to South Korea. However, only 5.22% of our survey sample personally knew a North Korean.

That data suggests that most South Koreans rarely think about North Korea, which appears more consistent with desensitization theory. The results suggest that South Koreans pay little attention to the numerous South Korean newspaper articles that are about North Korea. South Korea’s news has been cited as sensationalist and repetitive which could encourage the majority of readers to tune out North Korea coverage and a few readers think more about the click-bait stories coming from the media.

That data suggests that most South Koreans rarely think about North Korea, which appears more consistent with desensitization theory. The results suggest that South Koreans pay little attention to the numerous South Korean newspaper articles that are about North Korea. South Korea’s news has been cited as sensationalist and repetitive which could encourage the majority of readers to tune out North Korea coverage and a few readers think more about the click-bait stories coming from the media.

Our data more broadly finds that the frequency in which South Koreans think about North Korea positively corresponds with support for unification under several conditions, believing unification will occur in their lifetime, and concerns about North Korea’s nuclear weapons, but perhaps surprisingly, does not correspond with concerns about military conflict with North Korea.

If South Koreans are rarely thinking about North Korea, then they likely are not as worried about the issues that Westerners often assume are most important. The South Korean government frequently emphasizes eventual reunification with North Korea, but if South Koreans are rarely thinking about North Korea and thus reunification more generally, then this may partially explain why South Koreans seem generally unprepared for the social changes that would follow reunification. Additionally, despite frequent reporting on North Korea’s nuclear weapons, many South Koreans do not appear particularly concerned about a program that seems more to deter the U.S. than anyone else, suggestive that even if they do not believe North Korea should have such weapons, they do not view them as an existential threat.

North Korea may be able to capture the attention of American and South Korean intelligence, but capturing the continued attention of most South Korean citizens may be more elusive.