If America Re-enters Libya, it Must First Build Trust

“It was an act of piety, not war, done with the blessing of the UN, but with no thought to American interests, and, as it turned out, little interest in victory.” – Titus Techera

Titus Techera was describing America’s 1993 intervention in Somalia, but he may also have been speaking of the 2011 toppling of the Muammar Qaddafi regime in Libya, led by the U.S.

Now the U.S. wants back into Libya, after four years of Donald Trump’s hands-off approach.

There’s a new U.S. ambassador to Libya, Richard Norland, who is also a special envoy tasked with leading diplomatic efforts for a negotiated settlement.

The U.S. government is also approaching U.S. energy services companies about investing in Libya to signal that the country is safe and open for business. But many Americans are dubious about a return when the country faces more pressing domestic issues, such as crime and inflation, and a majority of voters believe war in the Middle East is increasingly likely.

If America returns to Libya, can it bring anything other than money? Even that may be in doubt after it ran up a $6 trillion dollar tab for the failed post-9/11 military expeditions. Then there’s the cost to the U.S. of COVID-19, over $16 trillion by one estimate. And there’s no saying what looming inflation will cost the American taxpayer.

Money aside, why should the U.S. care? It doesn’t need Libya’s oil and natural gas. And isn’t Libya a neighbor of Europe?

Yes, it is, but the U.S. led the UN-sanctioned effort to overturn the Qaddafi regime based on the lie that the regime was committing genocide against its own people when the real goal was regime change. It happened because Samantha Power and Susan Rice felt remorse about the Rwanda genocide, and Hillary Clinton, with her eye on the 2016 election, wanted a foreign policy win under her belt.

American guilt and ambition were supplemented by French fear: the Nicolas Sarkozy government in France took the lead advocating for the UN Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force against Qaddafi forces possibly because Qaddafi was starting to talk about his financial support for Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign.

The long-term downside, aside from the deaths and destruction of infrastructure, and illegal migration and the attendant disruption of Europe’s politics, was felt in Tehran and Pyongyang, where Kim Jong-Un and Ali Khamenei drew the obvious conclusion: if you surrender your nuclear weapons, the U.S. will overturn your regime. This unforced error will complicate America’s regional diplomacy for decades to come.

If America wants in, what can it offer to help fix this disaster?

The United Nations has done yeoman work since 2011 to help the Libyans create a political process. It midwifed an interim government that was seated in March 2021 and will lead the country until national elections in December 2021.

Those elections may see the factional leaders and warlords try to trade their camouflage for Brioni. Whether they succeed or not is up to the Libyan people, but the U.S. has a role if it can solicit the support of the states that are the patrons of the local personalities.

The interim government, headed by a three-member presidential council, has taken the place of the internationally-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA). The GNA was backed by Turkey and Qatar.

The GNA’s rivals were the elected House of Representatives and the Libyan National Army (LNA), commanded by Khalifa Haftar, a former Libyan military officer and long-time U.S. resident. The LNA was backed by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and France. The UAE and Saudi Arabia are opposed to the Muslim Brotherhood, which is supported by Turkey and Qatar, and influenced the GNA.

The presidential council will administer the government until the December elections and the supporters of the GNA and the LNA will actively try to shape the result. If the U.S. is again involved in the Libyan peace process it won’t just be dealing with the GNA and LNA alumni, but with their foreign patrons.

Libya’s Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah is hopeful that foreign fighters will soon leave his country, though many have obviously missed the January 23, 2021 deadline. Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan also wants foreign fighters to leave, though he probably also wants an exception for Turkish troops. If the U.S. wants to play a constructive role in Libya, it can engage with the patrons of the local pols, but is it ready to do the give-and-take required to correct its disastrous intervention?

To start with, the local figures aren’t rag-tag local gunmen but the clients of powerful regional governments who are rightly concerned with stability in Libya and the Mediterranean region, and the malign influence of the Muslim Brotherhood. Russia signaled the likely response of the patrons by sending another 300 Wagner troops into Libya.

Unfortunately, the U.S. has weakened relations with most of them, so they may be looking for an incentive to cooperate. Any “incentive” means something concrete, not just “I’ll gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today.”

Their expectations were raised by one man: Donald Trump.

The Abraham Accords, the normalization of ties between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan, happened because Trump was personally engaged. The other reason was Trump gave something to get something: for the UAE, it was the F-35 combat aircraft; Morocco got the recognition of its claim to Western Sahara; and Sudan was removed from the sanctions list as a state sponsor of terrorism.

The U.S. will have to pay attention to bilateral relations to see real progress in Libya. But can it?

Turkey was sanctioned for buying the Russian S-400 missile defense system, instead of the U.S.-made Patriot system. Recently, Turkey offered to guard the airport in Afghanistan’s capital Kabul, which may be necessary for the continued presence of foreign embassies and international aid organizations in the wake of the U.S. retreat. (The Taliban nixed that idea as “unacceptable.”) Biden described his recent meeting with Erdogan as “very good,” but there’s been no word if Turkey received the “political, financial and logistical support” it requested. On the other hand, Erdogan told Biden Turkey won’t change its position on the S-400 system so the U.S. administration may have to think creatively, instead of relying on its go-to solution: more sanctions.

The U.S. has so-so relations with Qatar, remarkable considering the amount of cash it spends on representation in the U.S., which is more of a commentary on Washington, D.C. than Doha, but it has been suggested as a training site for Afghanistan’s armed forces in the wake of the U.S. evacuation.

Longtime U.S. friends, the UAE and Saudi Arabia were threatened with the cut-off of weapons used in the fight against the Iran-sponsored Houthi militia in Yemen. Also, the growing relations between the UAE and China has alarmed the Biden administration which may reconsider the F-35 sale if the emirate doesn’t purge its telecommunication system of Chinese equipment.

Upon entering office, the Biden administration promptly released a report that claimed that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was responsible for the death of Saudi writer Jamal Khashoggi, then downgraded the relationship by denying MbS access to the president. The administration is also removing air defense batteries from Saudi Arabia, which won’t motivate the Saudis to support U.S. designs in Libya. And it may be an opportunity for Russia to offer air defense services to the Saudis via a government-to-government agreement.

Egypt’s regime is uncertain of U.S. support because Washington jettisoned longtime ruler Hosni Mubarak after two weeks of Arab Spring protests in 2011. After the military overthrew the subsequent government that was controlled by the Muslim Brotherhood, the U.S. delayed delivery of Egyptian helicopters in the U.S. for repair. Egypt returned the favor by reducing its purchase of U.S. equipment, and looked to Russia and France. The last major U.S. sale to Egypt was in 2010.

The abandonment of Mubarak had a significant impact on America’s image in the region. The real audience for U.S. support of the popular uprising wasn’t 400 million Arabs but 12 guys in palaces in the region who know when the pressure is on, America will abandon its friends.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Joe Biden reportedly had a productive meeting in Geneva, but will Russia be motivated to press its charge Haftar to support the political process underway in Libya? Economic sanctions are the foundation of U.S. policy towards Putin’s Russia. The U.S. national security establishment thinks more sanctions are always better and their Russian counterparts, such as Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Alexander Pankin, believe “The sanctions regime has always been in place. And it will remain so forever.” The U.S. will only be satisfied if the sanctions force regime change, which is the point, not the nonsense about “changing behavior.” So, if no relief is in sight, will Russia bother?

In an effort to prove Mr. Pankin correct, the U.S. is preparing more sanctions against Russia over the poisoning and imprisonment of activist Alexei Navalny.

Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE all have military airfields the U.S. can use to attack potential terror threats that emerge in Afghanistan. They aren’t likely to suffer retaliatory attacks unlike the other candidate host countries, such as Pakistan or Central Asian states, but if Washington needs their help in Libya that may figure into their negotiations with the Pentagon.

Then, how long will the U.S. stay committed? In recent years, aside from abandoning Mubarak; the U.S. withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002; in 2009, the U.S. canceled a decision to build a missile defense shield in Europe; and withdrew from the Optional Protocol of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations in 2018; the Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights with Iran in 2019; the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in 2018; the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019; the Paris Climate Agreement in 2020; and the Open Skies Treaty in 2020. The Biden administration is refusing to call the Abraham Accords the “Abraham Accords” and is busy undoing Trump administration policies. All of which make foreign leaders wonder if any American commitment will outlast the next election cycle.

The lesson is obvious: Agreements with the U.S. won’t survive a subsequent administration, so get paid now as U.S. promises have a negative net present value.

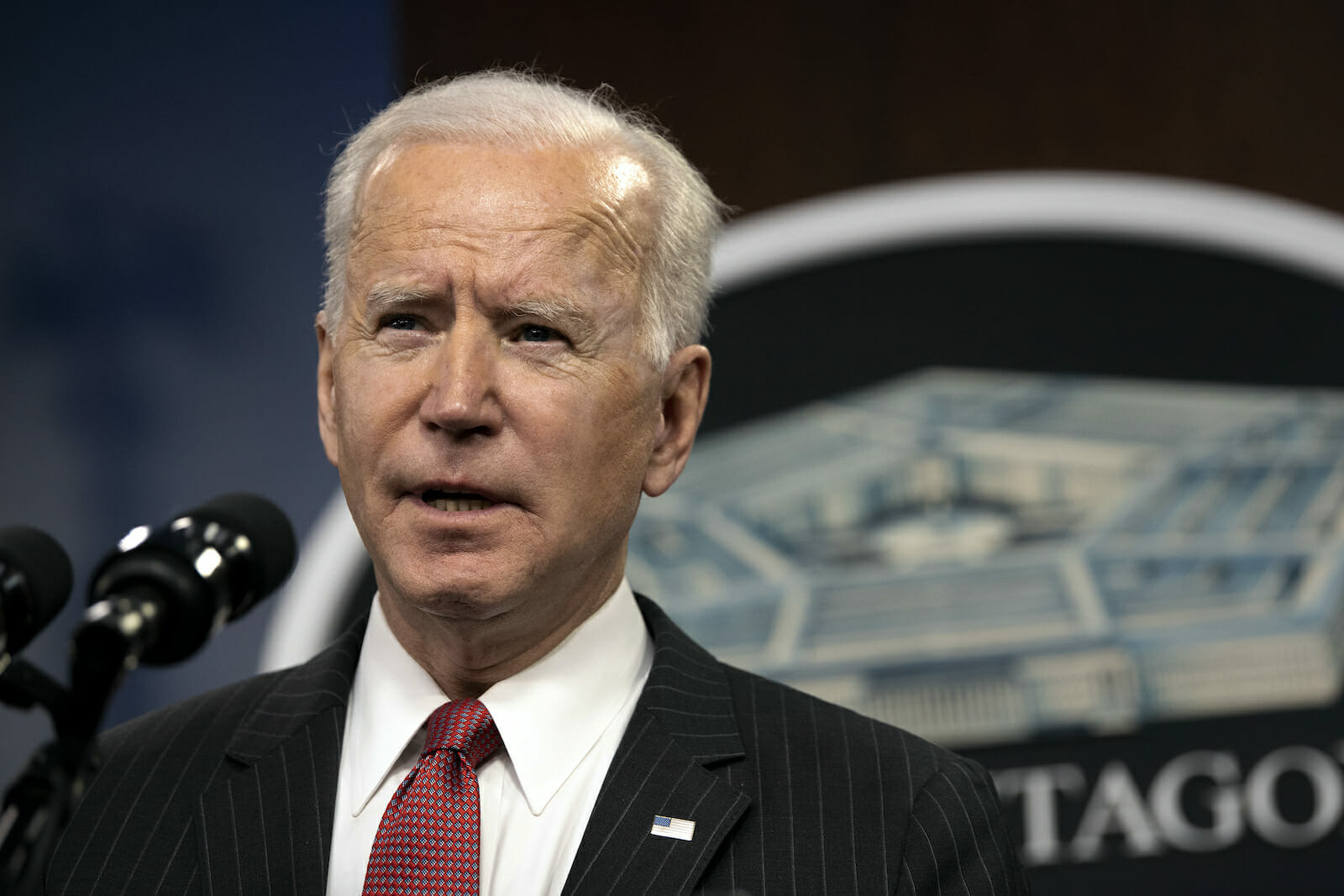

Will Biden personally get involved?

Trump took charge of relations with North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un, going so far as to step across the border to meet Kim, and his engagement with Kim at the 2018 Singapore Summit led to an “ongoing three-year de facto moratorium on North Korean testing of nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles.” Trump used his son-in-law as the intermediary to arrange the normalization between Israel and the Arabs. As a “career man” in the words of Putin, Biden will likely default to the civil service or longtime retainers, like Antony Blinken, his Secretary of State, but if responsibility is left in the hands of foreign affairs administrators, other leaders will correctly assume it’s not a priority for Washington.

In Libya, the U.S. must work to restore trust to justify its role, at a time when the Biden administration has strained relations with the foreign backers of local militias and politicians. Biden is a creature of the Beltway staff process – “The Blob” – and will be reluctant to engage foreign leaders à la Trump even though he calls foreign policy the “logical extension of human relationships.”

Now that Biden is finally the boss with his own foreign policy, will he prove former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates wrong and no longer be “wrong on nearly every major foreign policy and national security issue over the past four decades.”

If not, Donald Trump’s “I told you so” list will get longer.