In Venezuela, the U.S. Can Gain More by Doing Less

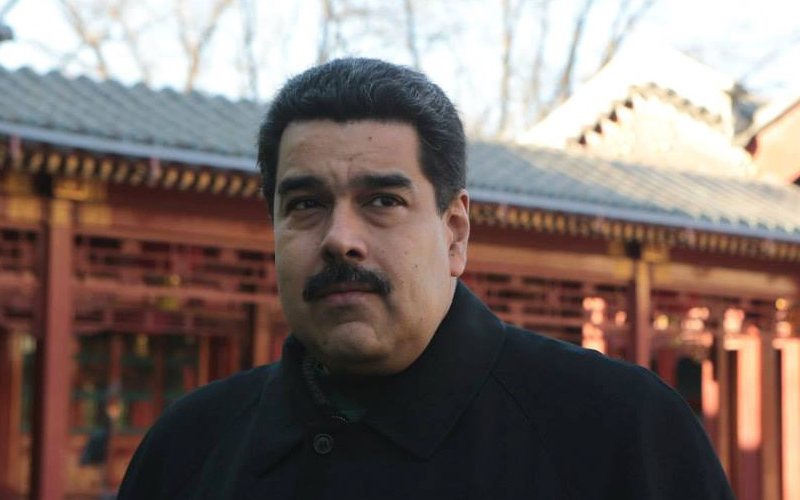

The present global atmosphere presents a set of frustrating challenges to American policy makers. With the MH17 tragedy in Ukraine, the continued destabilization of Iraq, and the on-going and very public violence in Israel and Palestine, it is understandable that legislators would turn to the United States’ backyard in pursuit of an easy win. That would appear to be part of the motivation for the House of Representatives’ passage, and the Senate’s consideration, of sanctions against the Venezuelan government in recent weeks. But Venezuela is a unique geopolitical situation, and the sanctions that have had some success chastening Russia and bringing Iran to the negotiating table would likely have limited success in changing the calculus of Nicolás Maduro’s government. In fact, sanctions could have the opposite effect.

International Support for Dialogue, Not Sanctions

Mediation talks provided by Foreign Ministers from the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and officials from the Vatican, representatives from the government and the opposition coalition party Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD) began on April 10th. Though the dialogue began with promise, by mid-May it had bogged down, each side accusing the other of bad faith. Some observers doubted the likelihood of government intervention in the judicial process to free some 200 hundred protestors who were still in jail, as the MUD has requested. Others, including the Colombian Foreign Minister María Ángela Holguín, have alleged the government entered into talks as a way to buy time, and was resisting any substantive progress.

Despite this frustration, sanctions have yet to draw multilateral support. In late February, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff dismissed comparisons between the situation in Ukraine and that of Venezuela.

Rousseff cautioned that a coup against the elected government of Venezuela would force regional trade bloc Mercosur to exclude the country.

In early March, despite American, Canadian and Panamanian demands for more substantive action, members of the Organization of American States (OAS) called for continued “national dialogue.” On March 31st, OAS Secretary General José Miguel Insulza reiterated the regional bloc’s resistance to action in Venezuela. Citing the lack of regional support for invoking the OAS’s Democratic Charter and punishing Venezuela, Insulza said that the age of intervention was over.

Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa, who has in the past attributed the Venezuelan economic crisis to mismanagement by the Maduro administration, has also repudiated U.S. action in Latin America. In a May 23rd interview with Russia Today, Correa called U.S. policy towards the region “terrible,” and described it as an “intolerable double standard.” That same day, Foreign Ministers from UNASUR member states, many of which are U.S. allies, issued a statement opposing U.S. sanctions. According to the statement, sanctions would only hinder the Venezuelan people’s ability to overcome difficulties with independence and democratic peace. Opposition to intervention is not limited to Venezuela’s neighbors. The 120 countries of the Non-Aligned Movement expressed support for Venezuela in the face of what Foreign Minister Elías Jaua called “US and right wing interference.”

The U.S. Push for Sanctions

Despite this broad based opposition to U.S. action, the push for sanctions has existed since mid-March. Democratic Senators Robert Menéndez and Bill Nelson and Republican Senator Marco Rubio introduced legislation that would target members of the government accused of violating human rights. Florida Senators Nelson and Rubio have met with Venezuelan opposition supporters, and expat Venezuelans have built a base of support in Florida, much like the Cuban community there. Similar measures advanced through the House and Senate Foreign Relations Committees, culminating on May 28th, when the full House passed a bill, ushered along by Florida Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, that would freeze assets and visas of government officials. While this bill incurred opposition from a number of Democratic congressmen, earlier this month Senate Majority leader Harry Reid expressed support for the measure.

Imposing sanctions is a losing gambit, and not only because of the international opposition outlined above. It is a tactic the Obama administration itself is against. Deputy Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Roberta Jacobson has been at the front of the administration’s push back, saying repeatedly that the Venezuelan government and opposition must be given space to talk. Moreover, Jacobson has countered that imposing sanctions now would take a future bargaining chip out of the opposition’s hands. Jacobson’s predecessor Arturo Valenzuela echoed this sentiment, calling sanctions “counter productive” and stressing the need to exit the spiral of polarization in order to find a solution. There is even a rift between Congressional advocates and the Venezuelan opposition whom they hope to support. Ros-Lehtinen has spoken approvingly of measures that would suspend the U.S. purchase of some 800,000 barrels of Venezuelan oil per day. But this would be a kind of broad, “sectoral” sanction opposed by the opposition.

More damaging, imposition of sanctions by the U.S. could rally support for a government that is losing popular backing, and it would not be the first time. When late President Hugo Chávez made plans to visit Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein in late 2000, 73% of Venezuelans opposed the trip. However, after the State Department condemned the planned meeting, 62% of Venezuelans supported Chávez.

Sanctions might allow the Maduro administration to withdraw from the dialogue, and recast the conflict as one between his government and the United States, rather than one between the government and the people, said a Venezuela observer and senior fellow at the Washington Office on Latin American, David Smilde. Governing Socialist Party (PSUV) spokesman Jorge Rodriguez is on the record saying it would be an honor to be declared an enemy of the United States. Smilde has also pointed out that sanctions targeted at specific individuals with no clear methodology would contravene rule-of-law standards and alienate allies in the region.

Recent polling has also revealed that sanctions against specific officials are seen by many Venezuelans as an attempt to forcibly remove the current Venezuelan government. Current U.S. policy does little to dispel that notion. Moreover, strong ties with Russia and China, as well as other countries throughout the region and world, would undercut asset freezes and visa bans leveled against government officials.

Step Back to Move Forward

The political strife in Venezuela surely presents a frustrating situation for the U.S. government officials and legislators. They may feel that democratic and human rights standards, as well as vocal and concerted pressure from their constituencies compel them to act. But actions going forward must be more measured and must endeavor to support both allies in the region and the process from a distance. Taking a reduced role in solving the crisis in Venezuela would not only take the anti-U.S. cudgel out of the Venezuelan government’s hands, but would also compel the opposition to craft a platform that appeals to a broader section of the population, something even opposition leader Henrique Capriles recognizes.

The only avenue that offers a chance of a long-term solution with the potential to satisfy both sides is one that lessens the appearance of U.S. interference and creates space for regional actors and bodies to muster popular support, builds a framework for talks, and shepherds the Venezuelan government and opposition groups through a productive dialogue. It may even be necessary for the U.S. to work with Cuba, a country whose interest in regional stability now aligns with the U.S., to ratchet down tensions. Members of Congress may think they have the tools to force the Venezuelan political crisis to achieve a quick resolution, but unilateral action and sanctions are likely to exacerbate and prolong the situation rather than solve it.