Health

Inside the Porn Economy: Gail Dines on Bodies, Profit, and Power

Dr. Gail Dines is the founder and CEO of Culture Reframed, as well as a professor emerita of sociology and women’s studies at Wheelock College in Boston. Drawing on more than three decades of scholarship on the pornography industry, she is widely regarded as an authority on how porn shapes culture, sexuality, and social norms. She has advised government agencies in the United States and abroad—including in the United Kingdom, Norway, Iceland, and Canada—and in 2016 launched Culture Reframed, which develops education aimed at building resilience to porn’s harms.

Dines co-edited the best-selling textbook Gender, Race, and Class in Media and wrote Pornland: How Porn Has Hijacked Our Sexuality, translated into five languages and adapted into a documentary. Her work has appeared across major outlets such as ABC, CNN, BBC, MSNBC, The New York Times, Time, The Guardian, and Vogue. A regular presence on television and radio, she is also featured in documentary films, including The Price of Pleasure and The Strength to Resist.

In her research and public advocacy, Dines argues that decades of evidence show a strong association between pornography consumption and violence against women. She contends that mainstream porn cultivates harmful sexual attitudes, lowers empathy, and normalizes misogyny, racism, and sexual violence. Distinguishing a radical-feminist, harm-based critique from conservative moralism, she focuses on measurable social effects rather than questions of private morality.

According to Dines, porn distorts how men and women understand sex, relationships, and consent. She calls for comprehensive, “porn-resilient” education for young people and for broader social responsibility in addressing the industry’s outsized influence.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: Today, I’m here with Professor Gail Dines, the founder of Culture Reframed. My first question, Gail: what is the connection between pornography and violence against women?

Gail Dines: We have over 40 years of empirical research from different disciplines that show that boys and men who consume pornography are more likely to engage in sexually aggressive behaviour, more likely to accept rape myths, more likely to develop harmful sexual attitudes toward women, and may experience increased anxiety, depression, and reduced empathy for victims of sexual violence. This happens because they are repeatedly exposed to depictions of sexual violence and objectification. Most mainstream Internet pornography today is hardcore—it’s cruel, brutal, and dehumanizing toward women.

As men and boys watch and become aroused by it, they internalize the ideologies embedded in these images. A key point about pornography is that it portrays women as always consenting, no matter how degrading or violent the act is. This gives the impression that women enjoy being mistreated, which is often far from the truth, as they may be coerced or paid to act in these scenes. This reinforces the harmful idea that it is acceptable to dehumanize and abuse women. We have substantial peer-reviewed research from fields such as psychology, sociology, and media studies that corroborates these findings.

Jacobsen: What research links pornography to sexual aggression?

Dines: Regarding the research linking pornography to sexual aggression, our website is a good resource. One in particular, titled “Understanding the Harms of Pornography,” lists many studies. Additionally, our academic library contains over 500 peer-reviewed articles on this topic. Scholars such as Paul Wright, Chyng Sun, and Jennifer Johnson have contributed important work. The strength of social science research is not in isolated studies but in the coherent pattern that emerges when we review a large body of work. The research shows a clear correlation between pornography consumption and violence against women.

Jacobsen: How does hypersexualized media align with human rights violations, particularly regarding youth?

Dines: Hypersexualized media, even content that isn’t classified as pornography, and pornography itself can be viewed as violations of civil rights because they infringe on young people’s ability to construct their sexuality. The multi-billion-dollar media and pornography industries are shaping the sexual attitudes and behaviours of young people worldwide, which strips them of their autonomy in this area. These industries commodify and monetize sexuality, taking control away from individuals and turning it into a product.

Young people deserve the opportunity to develop a sexuality that is meaningful to them, not one dictated by the interests of pornographers seeking profit. Additionally, there are significant human rights violations against women in pornography. The treatment many women endure in the production of hardcore pornography can be likened to torture, violating international human rights conventions. If the same acts were done to any other group, they would likely be recognized as torture. That’s how extreme much of mainstream pornography has become.

Jacobsen: What are the social and health consequences of pornography consumption?

Dines: Basically, pornography is shifting how we think about women, men, sex, relationships, connection, and consent—all of these issues. What you see in society is that when pornography becomes the “wallpaper” of your life, as it does for young people today, it becomes the main form of sex education. This shifts the norms and values of the culture, and it’s happening internationally. This is not a local problem. Any child with a device connected to the Internet is being fed a steady diet of misogyny and racism—there’s an incredible amount of racism in pornography—and the idea that men and boys have a right to ownership of women’s bodies, regardless of what women want. There’s also the notion that women’s bodies exist to be commodified and used however men wish. This sets up women and girls to be victims of male violence. Meanwhile, we are trying to build a world of equality between men and women.

Pornography shreds that possibility—not only in terms of sex but also in employment, the legal system, and more. It sends the message that women exist only to be penetrated, and often in the most vile and cruel ways possible. So, pornography undermines women’s rights across multiple levels and within multiple institutions.

Jacobsen: You raised an interesting point about the nature of consent. What is the framework of consent in pornographic imagery and in the industry itself?

Dines: First, let’s start with the imagery because the industry is slightly different. In the images, she consents to everything. The one word you rarely hear in pornography is “no.” It’s rare. If you go onto Pornhub or any other adult website, where most men and boys consume pornography, you won’t hear “no.” Now, there are some rape porn sites where the woman says “no,” but those are at the far end of the spectrum. I study mainstream pornography, such as what’s on Pornhub. In terms of consent, we often question whether a woman truly consents; this is where the industry comes in. While they might sign a consent form, we don’t know under what conditions it was signed.

Also, pornography is where racism, sexism, capitalism, and colonialism intersect. The poorer a woman is, the more likely she is to be a woman of colour with fewer resources, and the more likely she is to end up in the porn industry. These are not Ivy League graduates lining up to do this. These are women who have had few choices. When you have limited options in life, especially due to economic hardship, it is challenging to argue that consent is fully informed or voluntary.

Jacobsen: For those able to exit the industry, what are the ways they manage to do so, and what are the psychological and emotional impacts, as well as the physical effects?

Dines: It’s extremely hard for women to leave pornography. First of all, we know that women in pornography experience the same levels of post-traumatic stress disorder as prostituted women. Many of them are also under pimp control. The psychological, emotional, and physical tolls are severe, making it difficult for them to leave the industry.

And also, where are they going to go? Especially in pornography, where your image is everywhere, women who have been in the industry, even if they get out, live in constant fear that their employers, children, and partners will find their content online. The issue becomes extremely difficult. You never really escape pornography once you’ve been part of it. Even if you leave the industry, you’re never fully out of it because your image remains online. It can take many years to recover emotionally and physically.

Many women endure severe physical harm—STIs and injuries to the anus, vagina, and mouth due to the hardcore nature of the acts. What’s interesting is that, in the case of prostitution and trafficking, there are many survivor-led groups helping women exit the industry. This support isn’t as prevalent for women in pornography, and the reason is that these women feel so exposed. They feel vulnerable even after leaving the industry because their images remain there.

Remember, an image on Pornhub can go viral, spreading across all the porn sites, so you never know who has seen it. You never know if the person you meet has seen it, which creates a constant feeling of vulnerability.

Jacobsen: You made an important distinction between liberal feminism and radical feminism. Can you clarify that distinction about pornography?

Dines: Yes. The critical distinction is in the ideological framing. Radical feminists were among the first to highlight the violence of pornography—both in terms of the harm to women in the industry and the impact on women in society. Radical feminism grew out of a focus on violence against women. Over time, they recognized that pornography is part of that violence.

Liberal feminism, on the other hand, tends to be more neoliberal, emphasizing individualism. The argument often centers around the idea that “she chose it,” that it’s about sexual agency. But what we know about these women is that this is not a true sexual agency. If anything, it strips them of their sexual agency and does the same to all women. Women often look at pornography to see what they should be doing for the men who consume it. Radical feminists are anti-pornography because they see both its production and consumption as a major form of violence against women, and they understand that it contributes to real-world violence as well.

Jacobsen: What are the industry’s tactics, and how do they compare to those of the tobacco industry?

Dines: The pornography industry employs tactics similar to the tobacco industry, such as bringing in pseudo-academics to argue that there’s no harm, framing research in ways that downplay the issues, and lobbying. The pornography industry has a powerful lobbying arm, much like the tobacco industry did. They know the harm their product causes, but they’re not interested in liberating women from harm—they’re in it to make money.

And so, all predatory industries will do whatever it takes to make money, irrespective of the incredible social impact it will have. The United States is known for not having as strong a FACTED (Family Life and Sexual Health Education) program as Canada. However, Canada, at its best, still has its gaps.

Jacobsen: So, how does pornography act, as you mentioned earlier, as a filler for sex education and a particularly poor one for young people, and potentially for older people?

Dines: Let’s focus on younger people. Developing an interest in sex is a natural part of development, often starting from puberty. But because we don’t have good sex education, the content is outdated and doesn’t speak to the reality that kids live in today. So, where are kids going to turn when they have access to devices and a vast amount of free pornography? Pornography fills that gap, but poorly.

What is needed, and what Culture Reframed provides, is a porn-critical sex education curriculum. If you visit our website, we have a program for high school teachers (and some middle school teachers), which includes PowerPoints and detailed instructions on how to teach it. We don’t show pornography, obviously, but we focus on building porn-resilient young people. Unfortunately, in many cases, sex education isn’t prioritized, and many sex ed teachers aren’t even specialized in the subject.

They might be math or physical education teachers, told a month before, “You’re teaching sex ed.” We frequently hear from people who are unprepared and have no idea where to start. Interestingly, studies show that students immediately pick up on this lack of expertise. Research indicates that students are aware that their sex ed teachers don’t know how to teach the subject, don’t want to do it, and aren’t addressing issues relevant to their lives. As a result, sex education has effectively been handed over to pornographers.

Jacobsen: A question comes to mind. We’ve discussed liberal feminism versus radical feminism in framing the issue. But within radical feminist discourse, are there any internal objections or disagreements on this critical view of pornography?

Dines: Radical feminism tends to agree widely on this topic. Are you asking about internal conflicts?

Jacobsen: Yes, specifically within radical feminism.

Dines: Any disagreements are quite minor, mostly centered on how to define the issue or address it. But there’s a strong, unified belief within radical feminism that pornography is violence against women, both in its production and consumption. We have major arguments with liberal feminists, Marxist feminists, and socialist feminists. We don’t tend to have many internal debates about pornography within radical feminism. However, we do have disagreements on other topics.

Jacobsen: There may be surface-level critiques from traditionalist, conservative, or religious groups that object to pornography on moral grounds, often based on a transcendentalist or ethical view of sin. Yet, they seem to reach a similar conclusion as you do.

Dines: Yes, but the conclusions, although they may appear similar, are quite different. Right-wing moralists are often concerned with what pornography does to the family, particularly how it affects men. They argue that it may cause men to stray or damage family cohesion. Radical feminists, on the other hand, have a critique of the family as the place where women are most at risk, as we know from the evidence. We are concerned with the harm to women, children, and society in general, but our stance is not based on moralism.

We refer to this as a harm-based issue, not a morality-based issue. That’s not to say some right-wing organizations don’t adopt some of our arguments—they do—but the core driving force behind our opposition to pornography is different. They oppose it from a moral perspective; we oppose it because of the real harm it inflicts on individuals and society.

Jacobsen: What would a healthy societal view of sexuality and sex education look like?

Dines: Much of what we’ve built on Culture Reframed is what that should look like, to be honest. A healthy view of sexuality begins with the individual owning their sexuality. It evolves naturally as a person grows. Of course, it’s rooted in equality, consent, non-violence, and genuine connection and intimacy.

This doesn’t mean that sex is only for marriage or long-term relationships, but that there is some level of connection and intimacy involved. That’s what makes sex meaningful in the end. If you don’t know the person you’re having sex with, as is often the case in pornography, you become desensitized. That’s why the industry constantly escalates the content.

If you were to film regular people having sex, most of the time, it would be so dull that you’d fall asleep watching it. The fun and excitement come from actually having sex, not watching it. So, for pornography to hold viewers’ interest, they have to keep ramping up the adrenaline through more intense and bizarre acts.

Jacobsen: Is part of the core issue the dehumanization and depersonalization that comes with pornography? It seems like there’s a disconnection—people go to their computers, consume pornography, and then return to their regular lives as if nothing happened. It’s like their day becomes fragmented and disjointed.

Dines: Absolutely. That’s a great point. There have been studies done on this. One interesting study showed two groups of men: one group watched a regular National Geographic movie, while the other watched pornography. Afterward, they were asked to interview a female candidate for a job, and the chairs were on rollers. The men who had watched pornography kept rolling their chairs closer and closer to the woman. They also found that these men couldn’t remember the woman’s words.

This kind of behaviour shows how pornography impacts the perception of others, particularly women, and how it disrupts their ability to interact meaningfully in real-life situations.

So you’re right. When you think about it, much pornography is consumed at work. Then you leave that cruel world where men are depicted as having every right to women’s bodies and go back to working in a world with women where you don’t have those rights. It’s interesting because we have the #MeToo movement on the one hand, which is crucial for explaining what’s going on. On the other hand, pornography is working against everything the #MeToo movement is trying to say about consent and women’s bodily integrity. Even men’s bodily integrity is compromised in pornography—nobody has bodily integrity.

In pornography, the body is there to be used in any way possible to heighten sexual arousal, usually involving high levels of violence. I haven’t seen many films where this wasn’t the case.

Jacobsen: We’ve already covered building porn resilience in children, or at least how important it is. How far do gender inequality and sexual violence reflect each other in women’s rights movements, particularly within the frame of pornography?

Dines: Let me make sure I understand. You’re asking about the relationship between gender inequality and sexual violence and how this plays out in the context of movements like #MeToo, correct?

Jacobsen: Yes.

Dines: I addressed some of this earlier when I talked about equality in other areas of life and how pornography undermines it. Gender inequality and sexual violence are deeply intertwined. If there were no gender inequality, sexual violence would be unthinkable. Sexual violence is typically used to destroy and control women and to show power and dominance. That’s why we must call it “sexual violence”—because it weaponizes sex against women.

Without gender inequality, this kind of violence wouldn’t even be conceivable. It’s built into the very structure of gender inequality, and in turn, it perpetuates and exacerbates that inequality. It’s a vicious cycle. Gender inequality fuels sexual violence, and sexual violence deepens gender inequality.

Jacobsen: Just to be mindful of that, then. We talked about the psychological impact earlier. What are the similar psychological impacts on boys and girls, rather than the differences?

Dines: Similarities around what, specifically?

Jacobsen: In terms of pornography consumption and its impacts.

Dines: We know very little about girls. There aren’t many studies at all on girls’ exposure to pornography, and, as in many areas, girls and women are often under-researched. One of the few studies by Chyng Sun, Jennifer Johnson, Anna Bridges, and Matt Ezzell does show a few things. Some girls and women go to porn not to masturbate but to see what boys and men are doing, so they can reproduce that behaviour.

They also found that girls and women who become addicted to pornography, similar to men, lose interest in real-world sex, preferring pornography. They become isolated and depressed. So, if they do go down the route of addiction, the impact is quite similar to that on men, except they don’t become violent.

Jacobsen: What are the key points of feminist and anti-pornography activism, particularly in your book Pornland, intersecting with issues of gender, sexuality, and human rights?

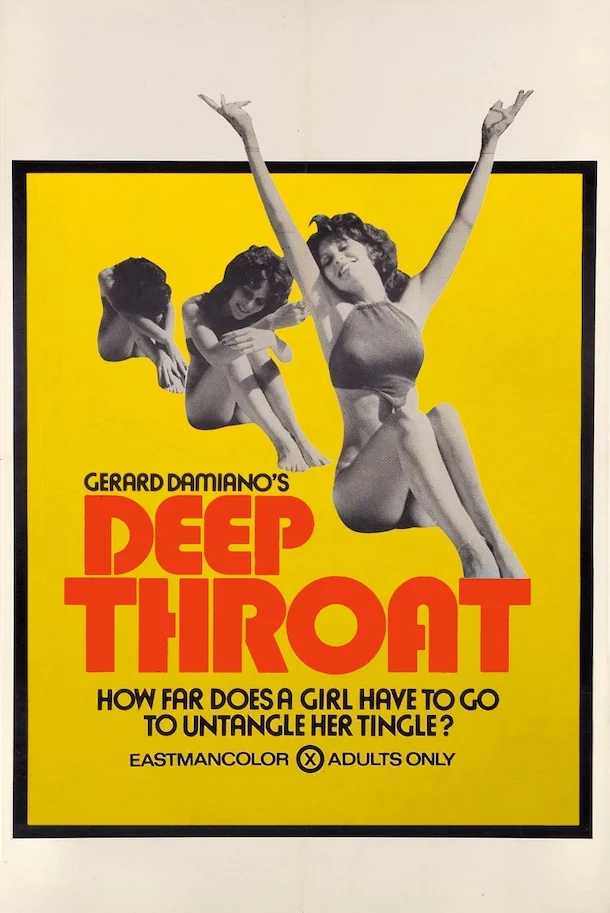

Dines: That’s what the whole book is about. Pornland was written to explain the modern-day pornography industry in the age of the internet. People were talking about pornography as if the Internet hadn’t happened. I take a radical feminist perspective, using research to back up the claims and focus on how pornography undermines women’s human rights.

There are chapters addressing racism, showing how women of colour are especially targeted, both for their race and gender. I also discuss how mainstream sites are increasingly making use of images of young-looking women—sometimes they could be children, it’s hard to tell. So, they might be underage or made to look underage.

The main argument is that we live in a world that is completely inundated and infested with pornography. As a sociologist, I’m interested in the sociological impact. I borrow from psychological literature but focus on the macro level. How is pornography not just shifting gender norms but cementing the worst aspects of them? It hasn’t invented misogyny, but it has given it a new twist and continues to reinforce it across various institutions.

Jacobsen: Gail, any final thoughts or feelings based on our conversation today?

Dines: We’ve buried our heads in the sand for too long. For people who weren’t born into the internet age, it’s hard to understand just how much pornography is shaping young people. There’s been a massive dereliction of duty on the part of adults in helping kids navigate this world they’ve been thrown into, often left to sink or swim on their own—and many are sinking. The kids I talk to feel overwhelmed by pornography, and studies back this up. Many wish there were far less of it because they recognize the adverse effect it has on their sexuality, their connections, and their relationships.

So, it’s time we step up and take responsibility as adults.

Jacobsen: Thank you for the opportunity and your time, Gail.