Culture

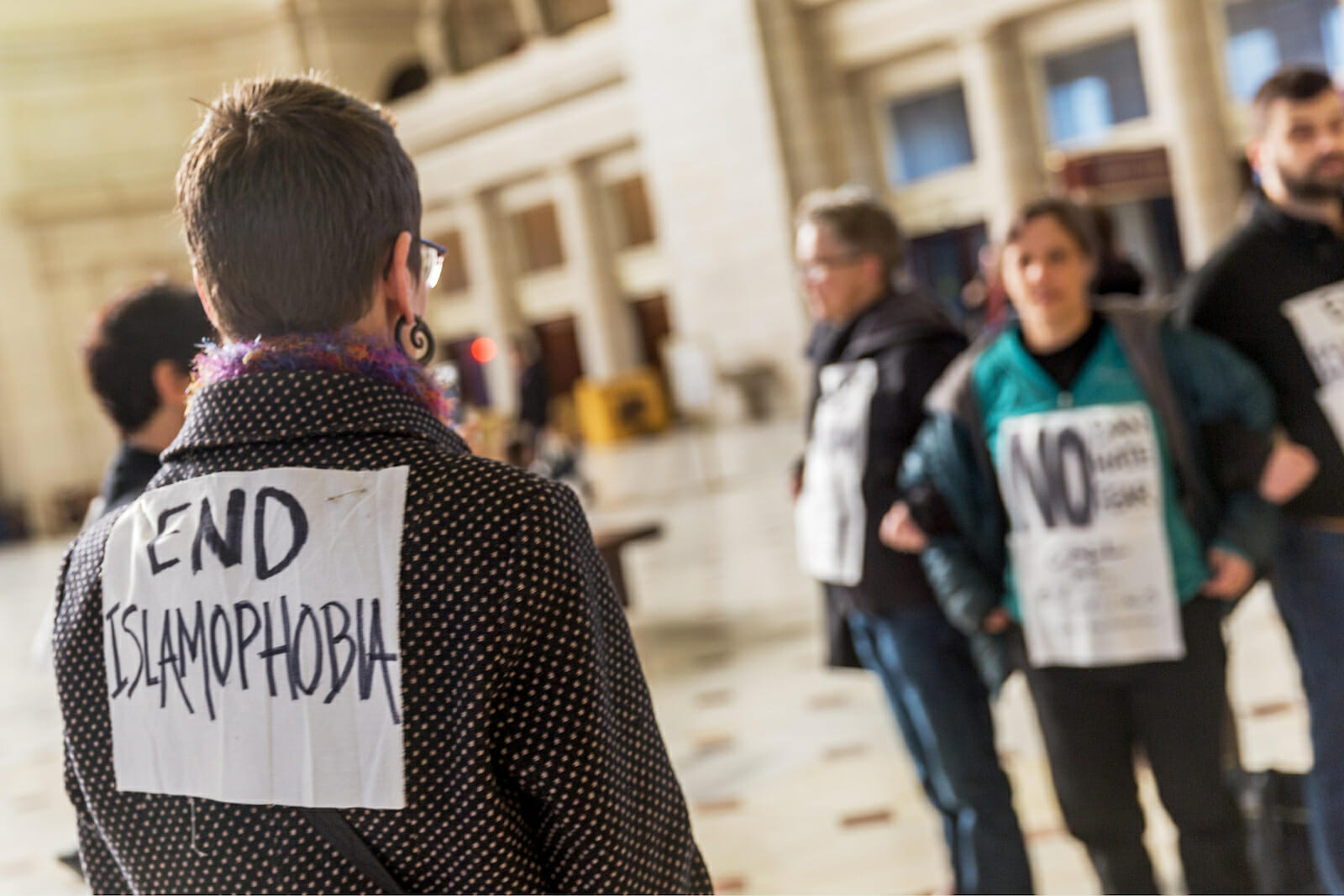

Institutional Islamophobia in the United States: Q&A with American Philosopher Daniel Tutt

The interrelationship between Islam and the West and the struggles that make integration in American and European societies difficult for the Muslims is a major debate these days. An American philosopher and author says Islamophobia is not a new invention and the difficulties faced by Muslims in describing and spreading their faith and the difficulties imposed on them by governments have together created the misunderstandings that have made the interfaith dialogue an arduous task.

Dr. Daniel Tutt (@DanielTutt) is an interfaith activist and philosopher. As a scholar activist, his work addresses Islamophobia and inter-religious dialogue. His writing and work has been published in Philosophy Now, The Islamic Monthly, the Washington Post and the Huffington Post. He has also published essays in three books on philosophy. He is a Professorial Lecturer at George Washington University.

“In a media environment where a relatively small group like ISIS can get 80 times more global media coverage than media coverage about the entire religion of Islam, it is no surprise that people don’t know what to think about Islam as a religion,” he said in an interview with International Policy Digest.

Daniel Tutt believes that fears of Islam as a religion have existed as a part of American culture and goes back to the Crusades and remains wedged within historical memories. Islamic institutions and schools have a major responsibility to educate the public about Islam as a faith and the contributions of Muslims to their societies.

In the following Q&A, Daniel Tutt responded to some questions about institutional Islamophobia in the United States and the role of the media in changing the narrative about Muslims in the West.

Do you consider Islamophobia a major challenge in the 21st century United States? There are sporadic attacks on mosques, hate crimes and other forms of prejudice against the Muslims that are sometimes underreported and sometimes investigated by government agencies. Does that mean that there is systematic Islamophobia in America?

I tend to agree with Franco Berardi, the Italian philosopher who wrote that Islamophobia is the principle means of aggressive identification in the western countries, from Europe to America. That is to say that Islamophobia has become a source for a resurgent identity politics, which serves as a sort of hyper glue for these political movements. Now most of the political movements that are responsible for inspiring hate crimes and violence towards Muslims are affiliated with resurgent white supremacist organizations and underground cells. But liberal Islamophobia is an even wider and more difficult phenomenon both to understand and to combat. Liberal Islamophobia is the more dominant form of Islamophobia compared to the resurgent racial and nationalist right wing Islamophobia, because it has a more integrated relationship to the western states, embedded in cultural diplomacy and liberal civilizing approaches to dealing with the “Muslim question.” Liberal Islamophobia is in many ways more insidious for Muslims than the more blatant neo-fascist, nationalistic and racist forms of Islamophobia because it is more ubiquitous in the lives of Muslims living in the western countries. Liberal Islamophobia, or institutionalized Islamophobia operates on a principle of what the late anthropologist and theorist Saba Mahmoud called “disciplinary inclusion.” So by liberal Islamophobia what I mean is a general cultural pressure that is placed on Muslims in western societies to become included as part of the larger society; but this inclusion is on terms that are disciplinary and that often compromise their principles and their politics. Mahmoud argued that this form of power is found in programs such as CVE or Countering Violent Extremism, a post 9/11 State Department initiative that focused on community and cultural engagement with Muslims. Muslims were requited as “allies” to the State Department and law enforcement efforts but the very set up of this program was based on a cultural litmus test and it set boundary line between what constitutes a “good Muslim” vs. a “bad Muslim.”

In an American context, I thought that liberal Islamophobia might mutate into something different with the rise of Donald Trump. But I rather think that the project of liberal, or institutional Islamophobia, which sought to reform Islam from within by identifying the most moderate Muslims to collaborate with, is now effectively on hold while Trump is in power. When Trump first came to power I thought he and his staff and base of support, all deeply entrenched in the far right Islamophobia industry, may provoke an out-and-out attack on American Muslim activists and organizations by criminalizing the Muslim Brotherhood and renaming the office of Counter Violent Extremism to the Office for Countering Islamic Radicalism. But he has done neither of these things. In fact, Trump is now moving under the leadership of Secretary of State Pompeo, to re-introduce some State Department cultural engagement to Muslim communities by hosting Ramadan iftars and other such commemorations. What I think this indicates is that institutionalized Islamophobia, which really depends on a close collaboration with domestic Muslim communities, has a lot of policy inertia, which even the far right Islamophobic base of the Trump team cannot undo.

So to answer your question more directly, yes, I believe that Islamophobia is systematic in America, but there are several layers to Islamophobia. I believe it is very important that we understand Islamophobia in its highly visible form—hate crimes, mosque vandalism, bullying in schools, and in its more invisible form, as an institutional network of power that polices inclusion into society and that seeks to shape the active direction of Muslim identities. We have some reporting from the Southern Poverty Law Center that indicate that the Trump ascension has resulted in a cultural environment where microaggressions towards Muslims, immigrants and people of color are on the rise. As a response to this generalized culture of anticipated racism, American Muslims have sought out partnerships with organizations seeking to advance racial justice. This offers an unseen opportunity for the American Muslim community to both combat racism both within the Muslim community and from outside of the Muslim community.

I also think it is essential to note that institutional Islamophobia is a danger to the Establishment Clause of the U.S. Constitution in that it seeks to actively shape the development of a religious tradition in America. For this reason I think that the rise of Trump is important for Muslim communities because it forces Muslims to work on the outside of power and to approach bridge-building with other communities, advocacy work and justice work outside the scope of the dominant institutions of American life. To be Muslim today in America is to face this immediate politicization of your identity.

There are thinkers and critics who say Islamophobia is being used as a shelter to protect Islam from being criticized and debated. They say Islamophobia as such isn’t a concern and instead is blocking the criticism of “Islamic fanaticism” and “radical Islam.” What’s your take on that?

I agree with this to a certain extent, but we have to understand why this is the case. Islamophobia produces a counter-reaction within some Muslim communities that actually drives commitment to being a Muslim. Islamophobia also makes Muslims feel very defensive and put up to the wall, always rendered suspect and forced to defend their religion. In an almost ironic way, Islamophobia facilitates a great deal of internal unity within Muslim communities. At the same time, there is a counter-tendency that drives many Muslims away from their faith and from Muslim community life. Because Muslims are forced to always respond to Islamophobia and present a face to the wider public seeks to convince their neighbors that they are not dangerous, etc. This means that Muslims actually are always describing their faith and religion to others. Most practicing Muslims feel that they are always answering questions about their faith and religion, which are often quite repetitive, boring, and clichéd. So the idea of Islam getting off the hook from criticism is a total misnomer in my view.

With that being said, there is a deficit in the public sphere of credible sources for discovering what Islam is really about as a religion. There are simply so many perspectives on Islam and its propensity for violence, its treatment of women and other issues that most people don’t know what sources to trust. In fact, one aspect of this phenomenon is that even if Americans know a Muslim personally, that relationship does not necessarily determine how that individual sees Islam as a religion. There is a cultural environment that determines how most people view the religion of Islam and much of that is influenced by a global media system that depicts Islam as a political and military ideology and associates Islam with terrorism.

Islamophobia is nothing new in fact. Historically, many Muslim communities actually struggled to spread Islam because of deep-seated Islamophobia. As a term, Islamophobia did not exist in the early turn of the 20th century, it was actually invented in the 1990s by the UK government, but you find some Sufi orders facing a difficult time in expanding their ranks and finding new followers as a result of generalized fear of Islam as far back as the early 1900s. In some Sufi orders, and here I am thinking in particular of the Chisti order, they would adapt their Islamic theology in a much broader New Age fashion so that they might appeal to an American audience who harbored doubts about Islam as a religion.

That is to say that America and western Christian societies have long struggled with Islam, seeing in Islam something other than an Abrahamic religion. If you read the speech that America’s first major convert to Islam, Alexander Russell Webb gave to the Parliament of World Religions in the late 1800s it sounds like something a Muslim leader would have given right after 9/11. He spoke of ways to combat the fear Americans have of Islam and the need to educate Americans about the religion.

So we have to understand that fears of Islam as a religion have been a long-standing part of American culture and this is something that goes back to the Crusades and remains wedged within historical memories.

There are reports that Islamophobia and anti-Muslim bias is encouraging Muslims to be more politically engaged in the American democracy, which includes registering to vote or running for political office. Do you think closer engagement between Muslims and the U.S. institutions will lead to greater understanding between them and bridge the gaps that seem to divide the American Muslims from the mainstream population?

As I said earlier, institutional Islamophobia is changing in that most American Muslim activists and organizations are not in a position to actively partner with government initiatives under the Trump administration. There is a more general spirit of protest and at times, resistance to policies such as the Muslim Ban and the anti-immigrant actions of entities such as ICE. And as you indicate, there is a new younger generation of Gen X and even Millennial Muslims who are working at the local level and running for City Council, Mayor and even the Gubernatorial level. Much of these political actors are left of center progressives who were mobilized by the Bernie Sanders campaign. It is a pretty incredible shift of political consciousness amongst American Muslims who voted in a majority for George W. Bush in 2000 and who fast-forward to 2016, supported the democratic socialist candidate Bernie Sanders in a major way. Not to mention here that there were a number of American Muslim political appointees under the Obama administration.

I do think that this wave of politicization will lead to a more positive development of the American Muslim ummah or community. I think this because one of the challenges American Muslims have faced is a class division that often takes the form or ethnic and racial divisions. New reporting from the Pew Research Group has indicated that close to half of American Muslims, [actually] 45% [of them] are at or near the official poverty line. So with the politicization that is occurring from the Trump moment, American Muslims have the opportunity to turn this political energy inward to look at ways to build bridges of solidarity amongst the diverse racial and class segments within the wider community.

What do you think about the role of the media in the United States in depicting a realistic and reasonable image of Islam and Muslims for their audience? What is the outcome of recurrent references to Jihadism and frequently conflating the entire followers of a faith with aggression and violence in TV shows and even movies?

The fact that the media propagates Islamophobic tropes and images is well known. The outcome of the proliferation of images of Islam being continually associated with violence and militarism is that it gives everyday people who do not know anything about Islam the distorted sense that Islam is not a religion but some violent ideology. So the media environment reinforces a more general climate where Islamophobia can come across as justified and legitimate because what people see of Islam appears to be very wicked, backwards and unenlightened. So to see beyond that image of Islam takes a lot of work in fact. The media’s depiction of Islam leads to a general climate of mistrust of all things Muslim and this corresponds to seeing Islam from marginal and conspiratorial perspectives. In a media environment where a relatively small group like ISIS can get 80 times more global media coverage than media coverage about the entire religion of Islam, it is no surprise that people don’t know what to think about Islam as a religion.

But I think there are reasons to be optimistic about the future of this situation. Muslims are actively working to change the media narrative on Islam by gaining influence within media industries, television shows and other sources of media production. To an extent, this is already happening in Hollywood where a number of television shows and movies now actively incorporate Muslim characters. But media representation is a major uphill battle which will take many years to change and like institutional Islamophobia, it faces the challenge of disciplinary inclusion which must be tackled head on.

Is it a myth or a reality that the supporters of right-wing politicians and neo-cons in the United States are genuinely scared of Muslims and believe that there’s going to be a takeover of their country by Islamist expansionists who want to impose the Sharia law, conquer America and plunder its resources and freedoms?

It is a myth that was propagated by a cottage industry of conspiracy theorists and former Cold Warriors who were desperate to find a national enemy after the fall of the Cold War. Muslims became this enemy for many of these people and after 9/11, the clash of civilizations became an active cause for them to generate a lost sense of American national unity. But this industry of Islamophobic writers, bloggers and policymakers has waned in recent years. For example, even though Trump is in power, the agendas of Robert Spencer, Pamela Gellar and Frank Gaffney have not really gotten off the ground. Their plan to preemptively ban Sharia law across America also failed. But these movements are not completely insignificant because they feed off of crisis. So if we face, God forbid, a terrorist attack, their more extreme approaches may find a more receptive audience, particularly in a reactionary administration such as the current one.

How can the Islamic institutions and schools effectively raise awareness of the realities of Islam, the perils and damages that Islamophobia inflicts on a multicultural society and make the voice of Muslims heard when it comes to their demands and aspirations?

I think that Muslim institutions and academics have been doing a number of positive things to educate the public about the true face of Islam. One piece of advice I would give to American Muslim institutions is to not conflate Islam with political problems. For example, there is a tendency within institutional Islamophobia to make a conflict such as Israel-Palestine and turn this conflict into a Muslim-Jewish or religious conflict, when in fact it is a political and human rights conflict.

I would also suggest that Muslim institutions and activists become more fluent with institutional Islamophobia and the threats that it poses to American Muslim communities. The work of Critical Muslim Studies, started by Salman Sayyid on Islamophobia is one great source for this perspective as is the work of Saba Mahmoud.

Khaled Beydoun has a new book on Islamophobia that also addresses these more structural aspects and power-based aspects to Islamophobia.