Books

Interview with Alex Finley, Former CIA Officer and Author of ‘Victor in Trouble’

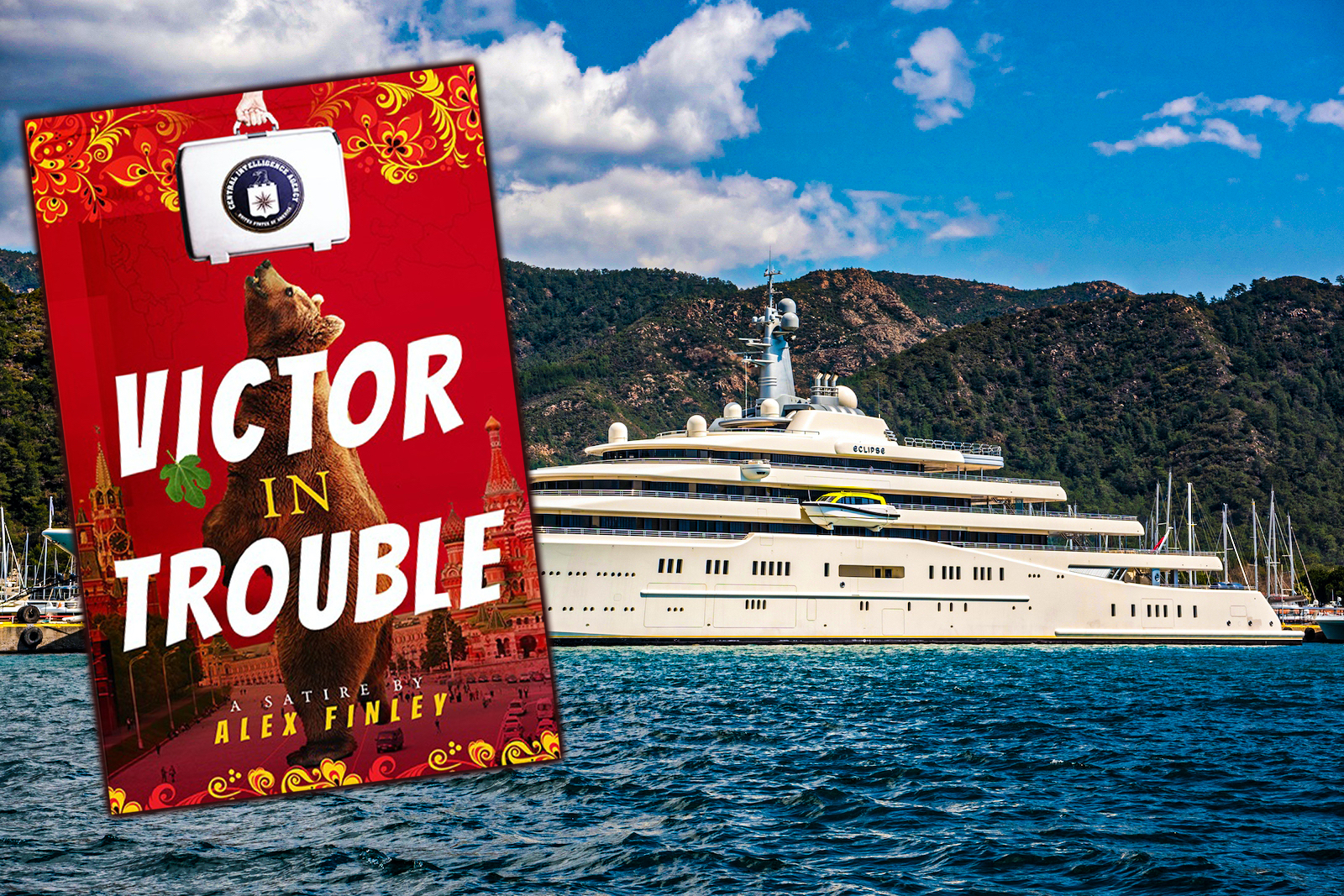

I had the opportunity to interview Alex Finley (@alexzfinley). Besides being a former CIA officer, Alex is the author of Victor in Trouble, which was released in late April. On social media, she also tracks Russian yachts using the hashtag #YachtWatch.

Our conversation, conducted over Zoom, is below.

Can you go over some of your background?

I’m a former CIA officer, I was in the agency from 2003 to 2009. And I was in West Africa, Europe, and Washington. And I was a reports officer, which means I was in the Directorate of Operations, but I was kind of the bridge between the analysts and the case officers.

So, I worked with the analysts to understand what our gaps in intelligence were, and what requirements they needed. And then I would go back to the operational side and say, “okay, who do we have? Who can answer these questions? Or who do we need to get to, to answer these questions? And how can we develop operations to help get those answers?”

Was it fairly challenging work?

Yes, of course, it was very challenging, especially, you know, I joined in 2003, as I said, very early 2003. So, it was shortly after 9/11 and just before the invasion of Iraq, so it was a sort of chaotic time, it was a hectic time, and there was a lot going on. And there were a lot of changes going on internally, as well, sort of in the, you know, in the aftermath of 9/11. And then, of course, in the aftermath of 9/11, excuse me, in the aftermath of the WMD issue in Iraq.

So, there was a lot of change at the time that I was there. So just bureaucratically, it was a challenge. But also, in terms of the work, it was a challenge. Of course, I like most people, I worked in counterterrorism. And, you know, every day you’re getting up and reading about who wants to kill us and how, and that’s difficult that wears on you, of course, and it makes it difficult sometimes to go back out into the real world and sort of be a normal member of society.

Not to dig into any specifics about your time at the agency, but how fondly do you look back at your time at the CIA?

Yeah, nothing that I can really talk about. I think overall when I look back at my time at the agency, I feel good about what I was involved in. I don’t agree with everything that the agency was doing at the time, but what I was involved in, I feel good about, and I met some of those most interesting people. And it feels good to participate in a mission and sort of protecting values that you know, that are your values, and you feel are a priority, but also just the adventure of it that you know. There’s a lot of fun that can come with a career in the agency, and you get to go to some places and do some things that you wouldn’t get to do with a normal sort of office job.

But politics stops at the water’s edge. Did you see that at the agency, as far as everyone you work with was apolitical and you were just focused on the mission?

Completely apolitical at the time that I was there. I had absolutely no idea what the political leanings of anybody was. We just simply didn’t discuss it. We had way too many other interesting things to talk about.

Was the agency in your eyes adaptable? Critics of the agency after 9/11 often said the intelligence was politicized. Did you see that people were willing to put aside their politics just to get the mission done?

Yeah, I didn’t see any issue with politics internally. But in terms of was it an adaptive bureaucracy? I would say no. In fact, actually, that’s my first book, Victor in the Rubble, was about the bureaucracy and how inefficient it was.

You know, I came in 2003 so I can’t speak exactly to how it was sort of in the earlier years but having spoken with other people who were there, you know, before 9/11, there was a lot more freedom for people in the field to sort of take decisions as they saw fit.

And as communications sped up and you have these instant communications, headquarters became much more involved sort of on a day-to-day operational basis, we used to call it “ops by committee,” you just had more and more people in Washington, who were weighing in and felt that they needed to have some stake in in an operation.

And that can be very inefficient, and very frustrating. So, the bureaucracy was a lot of what was frustrating me, and like I said, was the inspiration for the first book. Adding to that was that after 9/11, we had this huge increase. George W. Bush hired a number of extra personnel like 50% extra I think it was, to help fight this war on terror. And you had all these extra personnel who, you know, who had to do something. And while there was a certain amount, of course, to do over in the war zones, he also had a lot of people, who sort of wrote themselves into the process. And, you know, nobody wants to be what’s the word superfluous or something right? Every, you know, what’s the other word? Redundant. Nobody wants to be redundant, right. So, everybody sorts of finds a way that they can participate. And that can slow the bureaucracy down. So, it was not always super flexible.

Congress injected itself after 9/11 with hearings and oversight. Did you notice a lot of reforms or was the bureaucracy rather unyielding and unadaptable?

Well, so in response to this, so when I was there, so then in 2004, is when some of this reorganization started taking place. That’s when they created the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the DNI, and this was a response to these so-called intelligence failures. And I, I will say to my dying day, they were not intelligence failures. These were policy failures. But they have now been painted in the historical narrative as intelligence failures. But I hope that we’ll revisit that.

But so, the DNI was created sort of as a response to that. And it was controversial even at the time, and from the inside, it felt redundant. It was an added layer of bureaucracy. I specifically remember speaking to somebody over there who said, when I asked him, “well, what do you do differently that we’re already, you know, that we’re not already doing?” And he said, “the mission is still evolving.”

So, it took some time for the DNI to find its way. I’ve been out now several years, like I said, I left in 2009. So, you know, maybe it has found its footing, and maybe it’s much more appreciated. But at the time that I was there, it was clumsy and clunky and sort of a stumbling part of the bureaucracy.

For the past few years, especially under Trump, people respected Dan Coats and the IC professionals. People view them as apolitical, and just focused on the mission. And it became messy when politicians tried to politicize their agencies and those individuals.

I will totally agree with you on that.

What inspired you to write Victor in Trouble? It’s the third book in the series, correct?

So, I had been writing about and covering the Russian election interference in the United States, as well as Russian influence operations in Europe. So, I had already been covering these starting in 2016, after the election and I was in an interesting place, given my intelligence background, and my former life as a journalist. So, I was well-positioned to sort of explain to a general audience why what Russia was doing was an intelligence operation. And why this was a national security issue and why people should be paying attention to it. And that this wasn’t a political issue. So, I wrote a lot about that.

And what was frustrating me was that in the United States, that national security component of it was often not looked at. Whenever we discussed Russian influence operations or election interference in the United States it was viewed very much through a political lens, and, of course, very much with Trump in the center of that. And it was almost impossible to have a discussion about the national security implications without it becoming political and about Trump.

And for me, this was totally missing the point, because, of course, Russia was running very similar operations in Europe and elsewhere, that this was not about when Putin, you know, created this strategy, it was not about Trump, that was about destabilizing democracy everywhere. Because of course, democracy anywhere is a threat to dictators. So, it was this whole idea that he wanted to tear down these Western democracies to bring them down to his level and give him more leverage.

But that was lost in all of our conversations. I felt again because the politics got in the way and our politicians contributed to that. And so, Victor in Trouble grew out of that, and I wanted to write a story that showed a lot of what was happening. So, I wanted to show the Russian influence operations. I wanted to show what corruption and buying politicians can bring. I wanted to look at the role of dark money in politics. I wanted to look at disinformation. I wanted to look at the security situation in Europe and the Western alliance. So, the book, you know, talks a lot about Ukraine, actually. And there are pipeline and energy issues.

But at the heart of it is Victor Caro, the case officer who is running an asset, who is collecting intelligence on all of these operations, all of these attempts to buy and corrupt Western politicians. And so, Viktor finds himself, running his asset and collecting that intelligence, but also then having to protect his source from those very same corrupt politicians who are in positions of power. And those are all the different themes that I wanted to look at. And so, I used Victor as my vehicle to be able to do that.

Some of Victor in Trouble is set in Rome. Is there a reason why you picked that location?

I just think Rome was an interesting city. It’s a great city. It’s so chaotic. Victor actually talks about this at the beginning, when they arrive in Rome, there’s so much chaos, that it seems like a really great place to run operations because you can hide the operations under the chaos. It provides a lot of opportunities. And also, I just love Rome.

But there also is a real historical reason also that it’s there. Part of my inspiration in this as well came from what was happening politically in Italy at the time. So as again, as I was doing this research and writing about election interference. A story came out in Italy, about Matteo Salvini, who is the head of La Liga, which is also their right-wing party there. And one of his top advisors was caught on tape, allegedly accepting Russian money to help finance La Lega in European Parliamentary elections. So that investigation is still ongoing in Italy right now. But to me, it was such a great example, again of how this works, and that it wasn’t just happening in the United States like this was a real concrete example of very similar things that we had seen happen in the United States. This was a very similar example but that was happening in Italy. And it was out in the press. It was something that I could talk about. And, and so that’s it. So, Italy also just became a great place to set the story.

NPR did a story that involved Vienna, Austria. And they talked about how Vienna during the Cold War was a hub of Western activity and Russian spies. Even today, they painted a picture of a bunch of spies still running around, meeting covertly.

I think a lot of those cities are still a hub of spy activity. I mean, again, just to go back to Rome. Italian authorities caught red-handed an Italian naval officer, I think, in a parking lot of a supermarket meeting with his Russian handler, and he was being paid 5,000 euros a month by his Russian handler. And then they caught him and they’re trying him and that was in the news. Joseph Mifsud is one of the characters from this election interference in the United States. He was a professor at a university in Rome, where a number of intelligence officers teach and there were some strange things that were going on there. And then he’d sort of disappeared.

There were reports that Christopher Steele when he got his information that he first gave it to the FBI representative in Rome. So, I don’t know the city’s there’s a lot that goes on in these cities. And not just in Europe. I mean, I think Washington, Virginia, I think it’s probably happening in New York, LA, San Francisco. It’s happening in all of these places, too. It just happens, you know, under the noses of most people who, you know, they don’t know, they don’t know what to look for. So, they don’t, they don’t realize, I mean, I know people who ran operations all over the world.

On social media, you’re tracking oligarchs and their yachts. Tracking these yachts can become difficult. Can you speak to how tricky this endeavor is? Who owns these mansions on water?

Tracking the yacht is actually very easy because there are apps out there, we can see where a yacht is. What the difficult part is figuring out who owns the yacht and what yachts are owned by whom?

So, it’s one thing to know, some we knew, Dilbar (a Russian yacht recently seized by Germany) we all knew the Dilbar was always here in Barcelona. And everybody knew that was Alisher Usmanov’s yacht. Everybody knows Solaris and Eclipse are Roman Abramovich’s yachts. But we’re now finding that Abramovich has a whole bunch of other yachts. So, it isn’t just a case of saying okay, well can we prove that Eclipse or Solaris, for example, are owned by a Abramovich or the Dilbar is owned by Usmanov, but do they own other yachts that we don’t even know about?

That is the hard part and then even once you can make the connection to say, “okay, we think that this yacht is owned by this person,” then unraveling all of those offshore companies and family members, for example, to go back to Dilbar again, Usmanov in the end on paper is not the owner, it’s his sister, but the sister has something like 23 bank accounts in Switzerland or something like that. But that takes government resources, right because you unless you get leaks, if it’s in the Pandora Papers or something like that, that’s a really difficult thing to get access to papers that would prove on paper who the final ultimate beneficial owner is.

#YachtWatch 🛥

At the request of the U.S., Russian Oligarch Suleiman Kerimov’s $300 Million Yacht Seized In Fiji https://t.co/KNwv21pMaZ— Melody speaks gif fluently🇺🇸🌻🇺🇦 (@UnpaintedMelody) May 5, 2022

Once you know that a yacht belongs to someone, or you suspect that a certain oligarch owns a yacht, watching where the yacht goes is actually pretty easy. You can do vessel finder and marine traffic and you can watch where the yachts are going.

But one of the things that we have seen is that some of them turned off their tracking system. So, the AIS, that’s the tracking system that sort of sends out pings and gives the position of the boat or any vessel. I mean, all big vessels have this. And a lot of these yachts at the beginning when the sanctions were starting, and they all kind of, you know, took off, you know, to run away from the sanctions. A lot of them turned off their tracking system and sort of the last place that they pinged was in Seychelles, or the Maldives, some are in the Caribbean.

And, you know, until somebody happens to spot one, I mean, eventually a yacht has to go into a port somewhere, right? It has to be resupplied and must get fuel, the people on board need food, so eventually, it has to go in somewhere. But once it goes into a port, is there somebody there who recognizes “Oh, hey, this is a yacht that people are tracking and haven’t been able to see for a week,” that’s a tough thing to line that up.

But there have been some that disappeared off of AIS for a while, and then in fact popped up you know, like in the United Arab Emirates, and some people who had been following #yachtwatch “Oh, hey, you’ve been talking about this yacht. I just found it here.”

Yachts strike me as flamboyant and a waste of money. But I guess if they can buy yachts, they buy yachts.

Well, this is it. I mean, you look at just Abramovich, for example. I mean, he owns about or more than $2 billion dollars worth of yachts, just yachts. That’s not his other assets. It’s not his mansions. It’s not anything or a football club or anything else. It’s just yachts. And yeah, it’s a little bit of an obscene way. It’s extravagant. But it’s a status symbol I think among the oligarchs, there is a little bit of a size competition among them, I would say which I, which I alluded to in the book. And yeah, and who, you know, who can have sort of the most extravagant accouterments and things like that. That’s, that’s part of the status symbol.

A lot has been made about Biden wanting to sell Russian assets like yachts. Once a yacht is impounded, I know it sits in drydock. But what happens to these yachts once they’re impounded?

So, none have actually been impounded. Because impounded implies that the government is taking control of them. So at this point, they’re frozen. Not a single yacht has actually come under the authority or control of any government authority.

So, it’s frozen in the same way that a bank account is frozen, it just has to stay in the same status that it’s in now. But unlike a bank account, a yacht doesn’t stay the way that it is now, without a lot of maintenance on it right? It will deteriorate.

So, for a number of reasons, these yachts need to be maintained. And one is that they, if they do go back, you know, sanctions are lifted and they do go back to their owner my understanding is that they have to be given back in the same condition in which they were when they were frozen, but also they’re a risk for the for the people in the port around it and to other boats. You know, these yachts like it, you know, this is a $600 million piece of equipment. It has to be, you know, the motor needs to be turned on a regular basis. The water needs to be checked all the time. It’s more than house maintenance that, you know, there are things that need to be done every single day. And if it doesn’t happen, then they deteriorate very quickly is my understanding.

And that’s not just a problem for the boat itself. If a boat that’s been frozen or detained, for example, catches fire, and there’s nobody there who’s been maintaining it to make sure it doesn’t catch fire, that’s now a risk to the entire shipyard into the entire port. So, it is in everybody’s interest that they be maintained safely. But who’s paying for that? Nobody knows that that part remains unclear. My understanding is that most of these boats that have been frozen, have a certain amount of crew still on them, who are doing at least a minimal amount of maintenance. But again, who’s paying for any of that is not clear?

Are the Russian sanctions targeting luxury goods effective?

I don’t think any single sanction on its own is effective. So if you say just the luxury good, is it effective? No. But and I don’t think seizing one single yacht is effective, no. But all of these things together, along with all of the other economic sanctions that we have in place might be effective. The idea here behind the sanctions is twofold, I think. One is you, you want to put pressure on the people who have been integral in Putin’s destabilization activities.

So, a number of influencers, and a number of oligarchs, they play a role in helping in the disinformation space by strategically spending their money in certain ways to help run these influence operations. So, they support a dictator, and they help him in his deep stabilization activities against the West, while at the very same time, living in the West and profiting and in taking advantage of all the benefits of our open societies and our democratic institutions and our rule of law.

So, I think one of the points of sanctions is to say, enough, you’re not doing that anymore, you’re now going to go and live in Russia, under that Russian dictator system that you have been supporting. And now you’re gonna let us know how you like it. And it’s not just you that’s going to do that, we’re going to send your children back, we’re going to send your wives back, we’re going to send your mistresses back. And none of you are going to have access to all of these things that you’ve actually been taking advantage of. You’re going to live like Russians in Russia, under the dictator that you have been supporting.

So, I think that is one aspect and through that, you might get internal pressure on the Kremlin, I don’t know, I don’t know if that will work. The other side of some of these sanctions against the bigger ones like against, you know, against the oligarchs, not so much on the luxury handbags or something. But the other side of that is it, you know, these guys are Putin’s wallet, and they are the ones who use the West to launder the money and to clean the money and to park the money. And, so you’re also trying to deny them that opportunity.

Some have pointed out that our sanctions are so effective that average Russians are suffering, they can’t buy food items for example. They’re going into poverty. Is there a risk that sanctions can be so effective that they’re driving Russians to resent the West?

I mean, I’m not an expert in that area. But I mean, I guess there’s a risk to that. But again, I think this time there’s been a big push to try to do very targeted sanctions. Putin is going to create whatever internal message he wants to create anyway. So, even if in the end, it isn’t us cutting off his money, and it’s just him using all of that money for himself, or to fight this war, I mean, they’ve been stealing, these guys are the ones who’ve been stealing from the Russian people.

So the Russian people who don’t have anything right now, it’s already because these oligarchs have taken all of the money out of Russia. And, you know, they control that informational space. So whether we’re the cause of the economic collapse, or whether they are internally, amongst this elite, you know, inner group, they’re going to blame the West. So, in that sense, I’m not, I’m not convinced that that matters, we’re going to be the bogeyman regardless, because, without a Western bogeyman, Putin’s world doesn’t exist and doesn’t make any sense. He has to have us as the devil.

Can you speak to where things stand with the war in Ukraine?

I mean, in terms of on the ground, I can’t say specifically, but to me, it’s about much more than Ukraine. For me, what’s happening in Ukraine didn’t come out of nowhere. It grew out of all of these influence operations that I was talking about. This idea that democracy anywhere is a threat to Putin. It’s now just the focal point of that struggle. And we’re in a much bigger struggle here than just Russia against Ukraine. This is really a struggle of democracy versus autocracy. And so what happens in Ukraine matters a lot to what, what the Western security paradigm is going to look like moving forward.

Do you think Putin was emboldened by our reaction to his annexation of Crimea, and also how we bungled Afghanistan?

I’m less sure about the Afghanistan thing. But I will say this, that absolutely the fact that we did nothing in 2008 when he went into Georgia. We did nothing in 2014 when he went into Crimea. We did nothing when he started assassinating people in London, in Salisbury, in Berlin, in the Czech Republic, we did nothing. When they interfered in elections in the United States, we did nothing. When they interfered and started buying politicians in Europe, we did nothing. So absolutely. He thought, well, so why not do this, they’re not doing anything.

We were still treating him as though he were a legitimate actor on the global stage. And he’s not, he is a pariah. And it’s taken us till now to get to that point. And I absolutely do believe that part of the reason he launched this invasion, this war, when he did is because he was convinced that his influence operations had worked, that he had disunited/destabilize the Western alliance to the point that he could again get away with this, because he had been getting away with all of the other steps up until now, because we were not united. Germany wanted their gas pipeline, you know. France had Le Pen yelling and screaming for the far right. Italy had Salvini. You had Brexit, which was actually Europe breaking up, which is what he was aiming to do. And the United States was totally paralyzed by its political polarization.

And so I really think he said, “Alright, we’ve achieved what this groundwork that I wanted to achieve before launching this war.” And I think he really thought this is the right time because our destabilization activities have succeeded. And to me, it was a relief that the West came together and said, “Oh, okay, this is now finally a wake-up call. That was enough of a wake-up call to get us to come together.” And in fact, the Western alliance did come together and say, “Okay, we have to put sanctions in these are sanctions that are going to affect us, as well, because that corruption came to us.”

That was a lot of the role of these oligarchs was to clean their money in the West and the services that go around with that, right? You look at the banks in Londongrad, you look at all the services that have grown around these incredibly wealthy individuals buying yachts, buying real estate, buying everything, buying everything, and using our system to do so. And so, in doing so they corrupted us, right, we became complicit in this corruption. And so, it was always going to be difficult to put the sanctions in place. And to say, this might hurt us, as well.

But I was pleased to see that, in fact, we did come together. And we have put together you know, a robust sanctions list. I think that there’s more that can be done. But I worried at the beginning, Germany didn’t want to stop Nord Stream 2, and the Italians were worried to stop luxury goods exports. Everybody had, you know, a little bit of a reason, well, this is really going to hurt my economy. But I hope that we’ve reached the point where we say okay, but there’s a bigger thing at stake here. And we all need to stay united in order to protect this democracy.

Do you think Biden has handled Ukraine effectively?

Yes, I think overall, I think he has the right ideas in mind. Whether he’s forceful enough or strong enough to carry out the things that he wants to do, I think generally his values and priorities are in the right place. Yes.

As Biden’s approach evolved? I know in the beginning, we put the kibosh on MIGs being handed over to Ukraine because we worried about escalation.

That may be. I have not been watching those details quite as much because I’ve been watching the yachts. I think at least this administration because a lot of people who are working for Biden also worked for Obama and my understanding is, that a lot of them were already, they didn’t think that Obama went strongly enough. And I think certainly in hindsight, right, when we look back that, you know, there were these fears in 2016, we understood that Obama didn’t want to look political by announcing, well, we know that Russia is interfering, you know, and they didn’t want to escalate.

I’m hoping that Biden and the people around him have learned that lesson that Putin doesn’t care, you know, he’s going to escalate whether, you know, whatever you do, yeah, he’s going to make his decisions anyway. And again, a lot of it is for his domestic audience and for his own, you know, power position. So, I do hope that a lot of the people who are around him around Biden and Biden himself, you know, have learned from that experience where we did go wrong in 2014, and 2016. And, and where we can be stronger to, you know, hopefully, finally, put an end to this and get a different leader into Russia.

That’s a great point. Is there anything you’d like to just add, anything you’d like my readers to know?

Buy my book, all readers should know to buy my book.