Islamic State Celluloid: Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and Witch Doctors of Terrorism

Nothing turns on the charlatan class of terrorism expertise than a video from an elusive, unknown destination, adjusted, modified and giving all the speculative trimmings. In reading, E.B. White suggested the presence of two participants: the author as impregnator; the reader as respondent. In the terrorism video, the maker consciously penetrates the shallow mind of the recipient, leaving its gurgling DNA to grow and mutate.

When Islamic State began its gruesome foray into the world of terrorist snuff videos, experts resembled overly keen cinephiles seeking the underlying message of a new wave. The burning of Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kasaesbeh in a cage in 2015 caused a certain rapture amongst members of a RAND panel. Was this, perhaps, a celluloid standoff with rival al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, whose affiliates had just slaughtered the staff of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in their Parisian offices?

Senior Adviser to the RAND President, Brian Michael Jenkins, could not “recall a single incident in modern terrorism where terrorists deliberately killed a hostage with fire.” There was “no religious basis for it this side of 17th-century witch burning.” Senior political scientist Johan Blank turned to scripture, finding “at least one specific prohibition of death by fire in the ahadith literature” on “the grounds that it resembled hellfire.” The inspiration had to stem from somewhere, and Blank’s judicious offering was Ibn Taymiyyah, “fountainhead of much current jihadi reinterpretation of longstanding Islamic orthodoxy.” Andrew Liepman, senior policy analyst, saw the video as a lucid moment of proof. “I wonder how much more evidence we need to confirm that ISIS is acting outside the norms of Islam.” Not modish, it would seem.

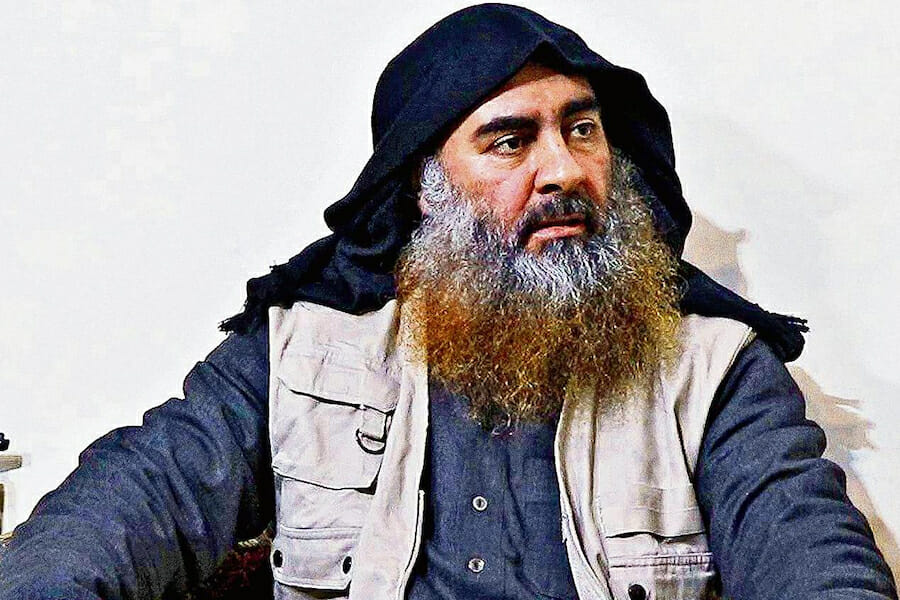

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of Islamic State, has begun to resemble, in no small part, previous heads of franchise terrorist groups who have become reproductions and simulacra of themselves. Terrorism is big business, stage sets, and props, all tweeted for good measure; it is bestial theatre that draws out the voyeurs, the google-eyed analysts, and the lunatic converts. Whether such heads are dead or not is of little consequence past a certain point: Baghdadi had supposedly been dead yet his corpse seems more than capable of putting together a presentation for audiences. It is also incumbent on those seeking his capture or death to claim his general irrelevance. Everyone did know one thing: the last time he performed on a public forum was the al-Nuri Mosque in Mosul in July 2014.

The video, aired on the Al Furqan network, is filmed in appropriately Spartan surrounds, but that is neither here nor there. Iraq Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi thinks otherwise linking, erroneously, the making of the film with the current location of the protagonist. “Regarding the location of Baghdadi, we can’t give intelligence information right now but it’s clear from the video that he’s in a remote area.” As is the fashion, neither the date nor the authenticity of the recording is verifiable. All else is a wonder, and even the Middle East Monitor is careful to suggest that the speaker was “a bearded man with Baghdadi’s appearance.”

Baghdadi lacks complexity in his message, never straying from the apocalyptic line. “Our battle today is a battle of attrition, and we will prolong it for the enemy, and they must know that the jihad will continue until Judgment Day.” He is mindful of the fruitful carnage inflicted by the Eastern Sunday bombers in Sri Lanka, and thanks them. Such acts, he reasons, were retribution for the loss of Baghouz in Syria.

The speculations duly form a queue, and talking heads have been scrambled into studios and Skype portals. This video may have been a retort, and reassurance, before the potential usurping moves of another ISIS figure of seniority, Abu Mohammed Husseini al-Hashimi. Hashimi had staked a claim in stirring up discontent against Baghdadi’s more extreme tyrannical methods. Not that he is averse to the application of hudud punishments (stoning for adultery excites him), and the quaint notion that the ruler of any Islamic State caliphate is bound to be a successor to the prophet Muhammed. Modesty is a drawback in such line of work.

Colin P. Clarke, senior fellow at the Soufan Centre, aired his views that Baghdadi’s “sudden appearance will very likely serve as both a morale boost for ISIS supporters and remaining militants and as a catalyst for individuals or more groups to act.” It was a reassurance that he remained the grand poohbah, atop “the command-and-control network of what remains of the group, not only in Iraq and Syria but more broadly, in its far-flung franchises and affiliates.”

The teasing out and ponderings on minutiae are not far behind. Resting upon a flowered mattress, and leaning against a cushion with an assault rifle by his side (nice touch for the old fox), it was bound to have an effect. The expansive beard caught the eye: The Washington Post noted that it “has greyed since his only other video appearance.” Previously, the paper noted, it had been “tinted with henna.” Then there was the AK-74 prop, a rather popular Kalashnikov variant reprised from previous showings in the video work of Abu Musab Zarqawi and Osama bin Laden.

Such superficial renderings, the stuff of terrorism kitsch, lends itself to the fundamental fact that Baghdadi might be somewhere, anywhere, or nowhere, a nonsense figure, to a degree, in a nonsense medium. The modern terrorist franchise is fluid and far-reaching. Followers need not feel estranged. They can use social media, cosy-up and wait for eschatological endings.

The pioneer of this terror mania (global yet local) was al-Qaeda’s Osama bin Laden, a figure who, along with his sparring counterpart US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, formed a perfect symmetry of simulative nonsense, the gobbledygook of post-2011 security. Each time US forces and their allies sought to target the slippery Saudi, he vanished. The raid and bombing of the Tora Bora complex in Afghanistan yielded no returns; the man was nowhere to be seen, having escaped, possibly, in female garb. Sightings and rumoured killings remained regular till the penultimate slaying in Abbottabad in May 2011. The man, declared dead on numerous occasions, was Lazarus in reverse.

Rumsfeld, for his part, insisted on those known knowns, known unknowns and “things we do not know we don’t know.” Unwittingly, he had given the age its aptly absurd epitaph, and with that, much work and fare for the witch doctors of terrorism keen to gorge upon the next video offering from their beloved subjects. Ignorance, in this case, not knowledge, is power.