Media

Julian Assange in Ithaka

“Keep Ithaka always in your mind. Arriving there is where you’re destined for.” – C. P. Cavafy, trans. Edmund Keeley

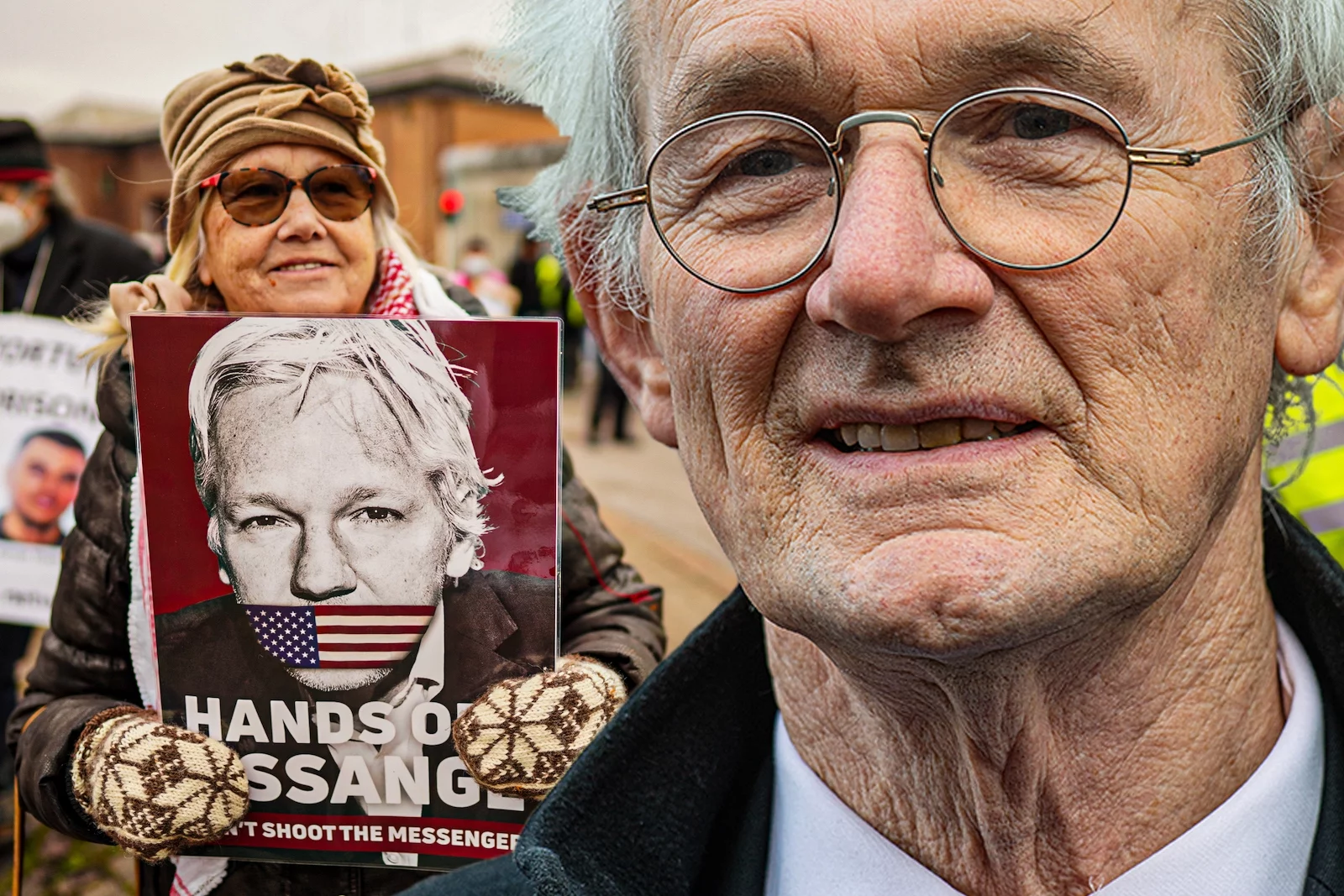

John Shipton, despite his size, glides with insect-like grace across surfaces. He moves with a hovering sense, a holy man with message and meaning. As Julian Assange’s father, he has found himself a bearer of messages and meaning, attempting to convince those in power that good sense and justice should prevail over brute stupidity and callousness. His one object: release Julian.

At the now-defunct Druids Café on Swanston Street in Melbourne, he materialised out of the shadows, seeking candidates to stump for the incipient WikiLeaks Party over a decade ago. The intention was to run candidates in the 2013 Senate elections in Australia, providing a platform for the publisher, then confined in the less than commodious surrounds of the Ecuadorian embassy in London. Soft, a voice of reed and bird song, Shipton urged activists and citizens to join the fray, to save his son, to battle for a cause imperishably golden and pure. From this summit, power would be held accountable, institutions would function with sublime transparency, and citizens could be assured that their privacy would be protected.

In the documentary Ithaka, directed by Ben Lawrence, we see Shipton, Assange’s partner, Stella, the two children, the cat, glimpses of brother Gabriel, all pointing to the common cause that rises to the summit of purpose. The central figure, who only ever manifests in spectral form – on-screen via phone or fleeting footage – is one of moral reminder, the purpose that supplies blood for all these figures. Assange is being held at Belmarsh, Britain’s most secure and infamous of prisons, denied bail, and being crushed by judicial procedure. But in these supporters, he has some vestigial reminders of a life outside.

The film’s promotion site describes the subject as, “The world’s most famous political prisoner, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange” a figure who has “become an emblem of an international arm wrestle over freedom of journalism, government corruption, and unpunished war crimes.” But it takes such a moment as Stella’s remarks in Geneva reflecting on the freshly erected statue of her husband to give a sense of breath, flesh, and blood. “I am here to remind you that Julian isn’t a name, he isn’t a symbol, he’s a man and he’s suffering.”

And suffer he shall, if the UK Home Secretary Priti Patel decides to agree to the wishes of the U.S. Department of Justice. The DOJ insists that their man face 17 charges framed, disgracefully and archaically, from a U.S. law passed during the First World War and inimical to free press protections. (The eighteenth, predictably, deals with computer intrusion.) The Espionage Act of 1917 has become the crutch and support for prosecutors who see, in Assange, less a journalist than an opportunistic hacker who outed informants and betrayed confidences. Seductively, he gathered a following and persuaded many that the U.S. imperium was not flaxen of hair and noble of heart. Beneath the impostor lay the bodies of Collateral Murder, war crimes, and torture. The emperor not only lacked clothes but was a sanctimonious murderer to boot.

Material for Lawrence comes readily enough, largely because of a flat he shared with Shipton during filming in England. The notable pauses over bread and a glass of wine, pregnant with meaning, the careful digestion of questions before the snappy response, and the throwaway line of resigned wisdom, are all repeated signatures. In the background are the crashes and waves of the U.S. imperium, menacing comfort and ravaging peace. All of this is a reminder that individual humanity is the best antidote to rapacious power.

Through the film, the exhausting sense of media, that estate ever-present but not always listening, comes through. This point is significant enough; the media – at least in terms of the traditional fourth estate – put huge stock in the release of material from WikiLeaks in 2010, hailing the effort and praising the man behind it. But relations soured, and tabloid nastiness set in. The Left found tell-all information and tales of Hillary Clinton too much to handle while the Right, having initially reveled in the revelations of WikiLeaks in 2016, took to demonising the herald. Perversely, in the United States, accord was reached across a good number of political denizens: Assange had to go, and to go, he had to be prosecuted in the United Kingdom and extradited to the United States.

The documentary covers the usual highlights without overly pressing the viewer. A decent run-up is given to the Ecuadorian stint lasting 7 years, with Assange’s bundling out, and the Old Bailey proceedings covering extradition. But Shipton and Stella Moris are the ones who provide the balancing acts in this mission to aid the man they both love.

Shipton, at points, seems tired and disgusted, his face abstracted in pain. He is dedicated, because the mission of a father is to be such. His son is in, as he puts it, “the shit,” and he is going to damn well shovel him out of it. But there is nothing blindingly optimistic about the endeavour.

The film has faced, as with its subject, the usual problems of distribution and discussion. When Assange is mentioned, the dull-minded exit for fear of reputation, and the hysterical pronounce and pounce. In Gabriel Shipton’s words, “All of the negative propaganda and character assassination is so pervasive that many people in the sector and the traditional distribution outlets don’t want to be seen as engaging in advocacy for Julian.”

Where Assange goes, the power monopolies recoil. Distribution and the review of a documentary such as Ithaka is bound to face problems in the face of such a compromised, potted media terrain. Assange is a reminder of plague in the patient of democracy, pox on the body politic.

Despite these efforts, Shipton and Assange’s new wife are wandering minds, filled with experiences of hurt and hope. Shipton, in particular, gives off a smell of resignation before the execution. It’s not in the sense of Candide, where Panglossian glory occupies the mind and we accept that the lot delved out is the best possible of all possible worlds. Shipton offers something else: things can only get worse, but he would still do it again. As we all should, when finding our way to Ithaka.