Learning from the Youth in Myanmar: From Regime Change to Misinformation and the Untapped Potential

Today’s generation of youth is the largest ever to exist globally. Young people often form the largest demographic in countries affected by armed conflict. Myanmar, our ASEAN neighbor, has been ruled by a military regime for more than half a century and has recently been in the forefront of the international political spotlight.

In 2010, a new quasi-civilian government took power and initiated developments by establishing a series of political, economic, and administrative reforms. Deep-rooted challenges were inherited in a militaristic and political manner leading to intensified fighting between armed forces and ethnic armed groups in several regions which often resulted in abuses against civilians. Today, the United Nations terms the fight between the Rohingya minority living in the state of Rakhine, a “textbook ethnic cleansing.”

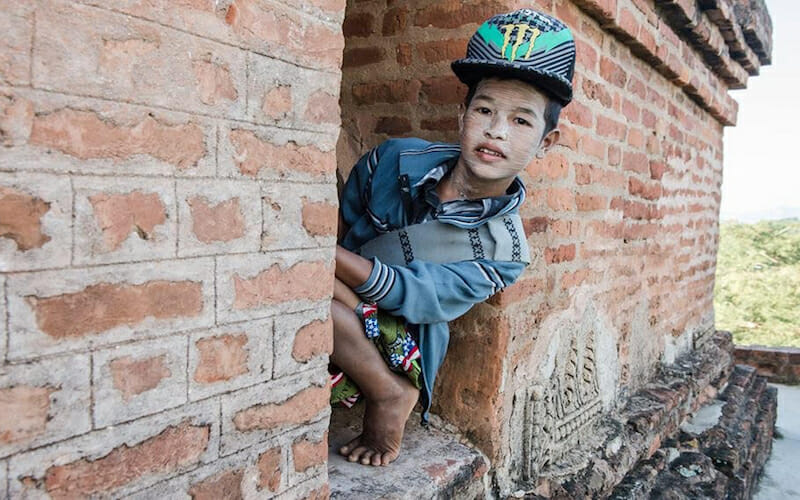

In March 2018, I traveled to the capital city, Yangon, for a Graduate research thesis project focusing on the youth civic participation in the country and the barriers that come with it. It is both a sensitive and equally controversial topic to analyze. However, I realize that not a lot of spotlight has been shed on the young people who make up more than 55 percent of the country. This is because the country has been catapulted by one significant barrier, fear.

In Myanmar’s history, youth have been involved in politics through social affair groups with the effort of sustaining peace. However, often they face obstacles in participation in regard to development and peacebuilding processes. I realize the grassroot issues are comparable to those young people in Indonesia. I recognized three main barriers:

Transitional Democracy

As Myanmar moves towards realizing its dream of being considered a credible democracy, the increasingly complex environment in the country has led to the stalling of this reform, as well as that of the peace process. The government has continually failed to adequately or effectively investigate abuses against the Rohingya, and has not acted on recommendations to seek UN assistance for an investigation into the violence.

While youth in Myanmar are increasingly involved in community and national efforts to sustain peace, they continue to face challenges in participating in peace and development processes at local, regional and national levels.

Young people may be less likely to organize due to a general mistrust of authorities or fear of a political and legal system that still does not provide full access to political and civil rights.

As late as 2014, student protesters who demanded a say in education reform were met with police repression and arrests which demonstrates that youth and student organizing is still associated with severe risks. Finding a platform on which to operate within an already limited space for civil society can be challenging for young people just starting to become active in advocacy.

In line with exploring the youth space in Indonesia, however, consistent characteristics and dynamics emerge as to how young people seek to create dialogue and mediate. Young people approach politically and socially charged issues in nuanced similar ways, often through initiating youth forums and networks, creating a microcosm of space that promotes dialogue amongst one another.

It is often youth groups who initially come together as a network collective across existing conflict lines that builds mutual trust.

Urban-rural divide

An interesting observation from the field interviews from local Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) was that there was a massive urban-rural divide in terms of the engagement strategies for both as well as the importance ascribed to each population. The conventional narrative has been to focus attention and efforts based on where there is the least amount of accessibility, thereby focusing most on the rural youth of the country.

However, given that most of the urban youth do not necessarily come with the baggage of conflict, efforts to actively mobilize and engage them remain limited. This gap must be addressed to foster communication and the understanding of the ‘other’ among the two groups. The urban youth must be mobilized to understand that no matter where the issues are taking place in the country, this is their problem as well.

Similar to that in Myanmar, the patterns of distribution of the total youth population in Indonesia is also unevenly distributed across the nation. According to a report by UNFPA, the concentration of youth in Indonesia is more likely to be in urban areas relative to any other age group. As such, this spurs discussion about youth’s rural-urban, inter-provincial, and inter-district migration. Big cities like Jakarta, Bandung and Yogyakarta have a higher youth populations which reflects more activism and civic participation within the region. This shows how mostly migration of information relies heavily on location as well.

Misinformation

Given how malleable youth are, the rise of social media as the only ‘credible’ source of information in the country is also an added challenge when thinking about youth civic engagement. With a plethora of information suddenly available and more easily accessible in the country, the problem of identifying real information versus propaganda or hate speech becomes an important issue to consider.

This makes it easier for youth to be influenced in a negative direction when they go back to their communities. With about 25 percent of the population having access to phones, 95 percent use Facebook as their source of information. On speaking with some donor organizations about the issue, they expressed frustration at the complete lack of ability to harness this rise of social media to their advantage.

There is, however, an increasing trend of verification groups on social media platforms such as Facebook, with people not just from Myanmar, but from all over the world, as an effort to filter information through various channels. There have also been efforts to use mobile phone technology, through the creation of apps as tools to better inform people, such as the Open Parliament app – which provides people a direct way of understanding their constitution. However, the extent of use and its impact remains to be seen.

In Indonesia, research conducted by Pew stated that Indonesia is one of the top 5 countries in the world where citizens aged 18-24 are more likely to use the internet and own a smartphone compared with people ages 35 and older. This shows that Indonesia is fueled by digital naratives. However, with technological advancement comes several barriers and the dark side. Most prominently are nefarious actors using social media to spread discriminatory messages and hate speech in the hopes of gaining the attention of politicians.

So how can both countries with similar youth conditions move towards a better sense of civic participation, more evenly distributed opportunity, and information filters that are both credible and accountable? The answer lies in a narrative shift.

There must be a shift from focusing on differences which are counter-productive to similarities. Stronger measures are needed to effectively harness the youth in the country and actively engage them in the development of their own communities.

This means moving from fixing problems to building on strengths; from reacting to risky behavior to proactively building on positive outcomes; from targeting marginalized youth to engaging all youth; and from regarding youth as a recipient of a certain service to treating youth as resources and active partners.