Letter to an Evangelical Friend

It is unwise to explain Islamism in terms of statements in the Quran, as some folks have done in trying to explain the rise of modern Islamist movements such as the Islamic State and al-Qaeda. Social movements, whatever their ideological claims, always develop in social contexts. The radical Islamism of our times has arisen in response to the advance of Western culture into Muslim societies.

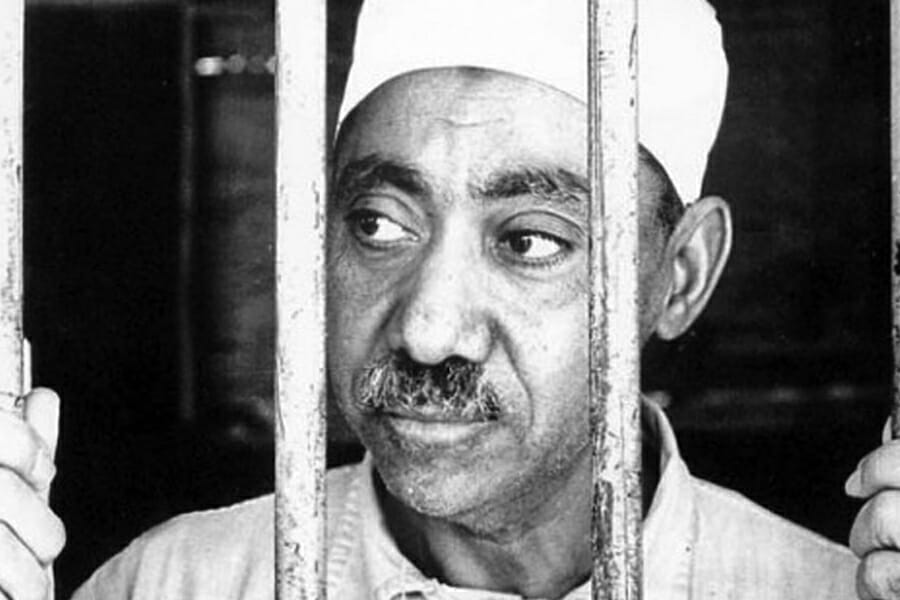

Muslims have for generations reacted to various alien cultural influences, but since World War II, many of the reactive movements have been influenced by the ideas of the Egyptian journalist Sayyid Qutb. Qutb spent two years in the United States in the 1940s and came away from the experience believing the United States, and indeed Western society was hopelessly decadent, and would eventually decline. However, he was alarmed by the advance of Western culture into Egyptian society. The problem, as he saw it, was not only Western influences but also the casual faith of most Muslims.

Qutb’s response to the advance of Western culture seemed to many young Muslims in the 1950s and afterwards to be the only hope for the salvation of Islam. They rejected all administrations that were not zealous for Islam, believing that only through extreme measures could the faith be saved in the face of the juggernaut of Western culture. So it was okay, even necessary, to take violent measures in the interest of the faith. It was from this viewpoint that a group calling themselves Islamic Jihad assassinated Anwar Sadat in 1981.

Qutb himself had been executed by Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1966 but his writings spread throughout the Muslim world. And while repressive measures in Egypt limited the ability of ambitious young Muslims to promote their Islamist ideas, Saudi Arabia provided a more receptive setting for the discussions and debates that would enable them to organize and clarify their agendas.

The Saudi regime, in fact, had long been allied with an Islamist movement that formed nearly 300 years ago. The original connection was established when Muhammad bin Saud, a tribal chief struggling to extend his grip on all of the Arabian Peninsula in the 1700s, obtained the endorsement of an Islamist preacher named Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, who opposed all innovations in Islam since the time of the Prophet. It was an alliance that a Saudi friend of mine called “a pact with the devil.” That alliance has produced a regime in the modern period that, despite claims to the contrary, represses any public expression that does not comport with Wahhabi religious thought and practice.

So, even though the young Islamists influenced by Qutb’s ideas found Egypt to be repressive they found Saudi Arabia to be an accommodating place to promote them. Osama bin Ladin was educated by Sayyid Qutb’s brother. When the Afghanistan-Soviet war heated up in the early 1980s, it provided a setting in which disenfranchised and frustrated young Muslims from all over the world, many of them in the Arab world could join a war whose moral grounds were unassailable to these Islamists: it was a Muslim cause against a “godless” state. The war provided a setting in which young men with Islamist ideas worked together in common cause in the name of Islam. It was this convergence of young Muslims seeking to advance the holy war for Islam that enabled Qutb’s ideology to become a formidable social movement.

In the aftermath of the war, once it was over, some of these men took their cause in the name of Islam to other conflicts — Chechnya and Yugoslavia, for instance. Others remained in South Asia and joined the new organization being formed by Osama bin Laden, which would be called al-Qaeda. (Another group, the Taliban, formed in 1994 to bring order to the chaos within Afghanistan.) Emboldened by the victory in Afghanistan, bin Laden in 1996 announced a holy war against the United States, thus resuming, as he saw it, the battle that was lost by the Turks (Muslims) at the gates of Vienna on September 11, 1683. Hence the attack on “the looming towers” in New York on September 11, 2001 — an act that objectified the perspective formulated by Sayyid Qutb in the 1940s.