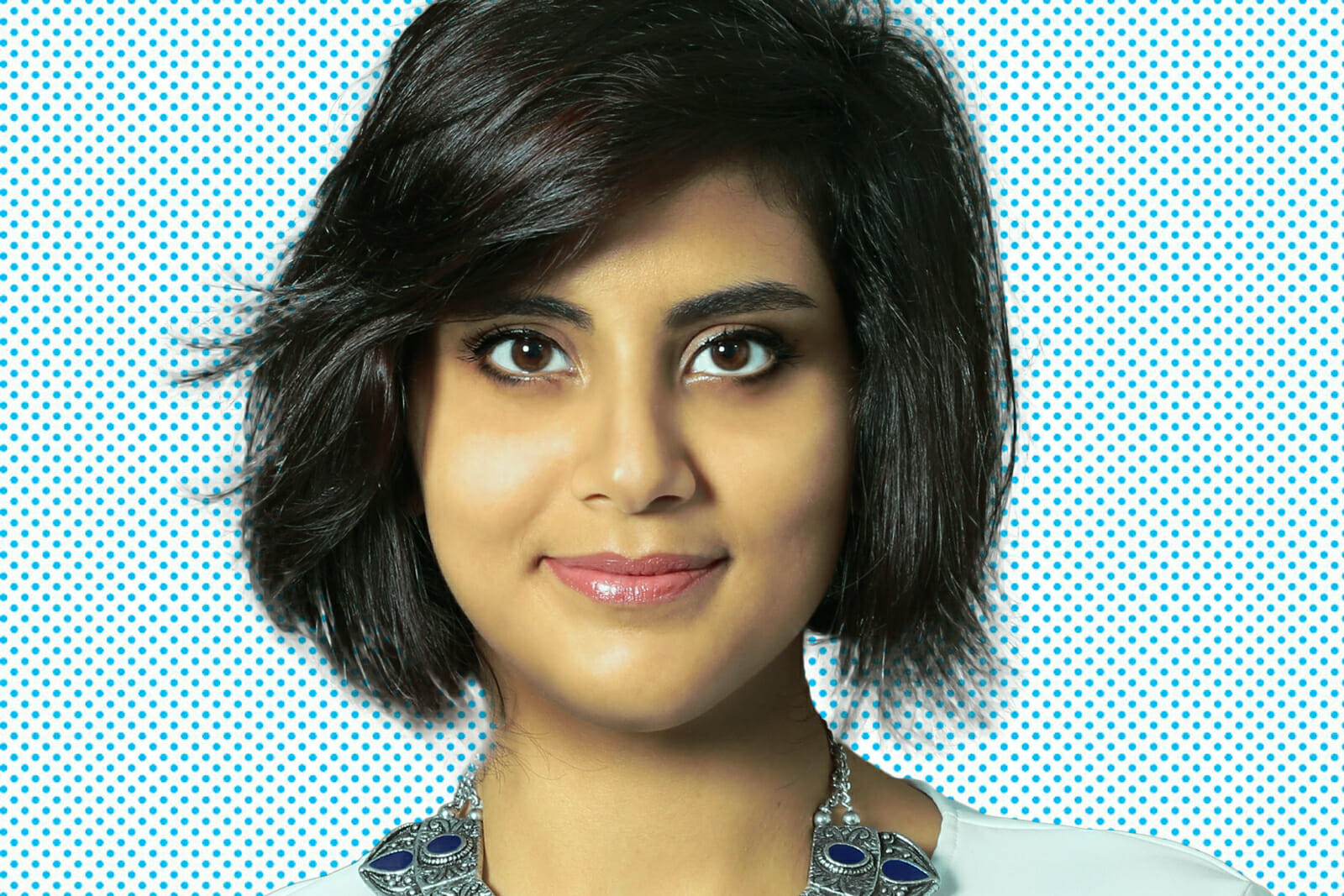

Loujain al-Hathloul and the Struggle for Women’s Rights in Saudi Arabia

“Undermining of national security” and “attempting to change the political system.” These are the charges that Loujain al-Hathloul was facing for demanding equal rights for women in Saudi Arabia. On December 28th, she was sentenced to over five years in prison by the Specialized Criminal Court.

Following the sentence, al-Hathloul’s sister, Lina al-Hathloul, posted on Twitter: “Loujain cried when she heard the sentence today. After nearly 3 years of arbitrary detention, torture, solitary confinement – they now sentence her and label her a terrorist. Loujain will appeal the sentence and ask for another investigation regarding torture.”

Even so, al-Hathloul’s prison sentence will end in March of 2021, since the court has suspended 34 months of her sentence and has calculated the prison verdict from May 2018 onwards, when she was first detained.

Loujain cried when she heard the sentence today. After nearly 3 years of arbitrary detention, torture, solitary confinement – they now sentence her and label her a terrorist. Loujain will appeal the sentence and ask for another investigation regarding torture #FreeLoujain https://t.co/E4msesGqjH

— Lina Alhathloul لينا الهذلول (@LinaAlhathloul) December 28, 2020

Loujain al-Hathloul was detained in 2018 and was charged under Article 6 of an anti-cybercrime law that penalizes the production and transmission of material deemed to impinge on public order, religious values, public morals, and life. For the over 10 months after she was detained, she was not charged with or tried for any crime. According to Amnesty International, she was waterboarded, given electric shocks, sexually harassed, and was threatened with rape and murder.

From 2018 to 2019, the so-called “Saudi crackdown on feminists” took place. It was a brutal policy that consisted of waves of arrests of women’s rights activists involved in the women-to-drive movement and the Saudi anti-male-guardianship campaign. The detained women and their supporters were tortured, with an advisor to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Saud al-Qahtani, present at some of the torture sessions.

The crackdown can be considered as the continuation of another wave of arrests in 2017 against intellectuals and moderate clerics. Human Rights Watch interpreted the arrests as being aimed at frightening the activists, stating, “The message is clear that anyone expressing skepticism about the crown prince’s [human] rights agenda faces time in jail.” The arrested campaigners were severely criticized in state media as “traitors.” Social anthropologist Madawi al-Rasheed interpreted the arrests as being part of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s aim to take all the credit for allowing women to drive starting in June of 2018.

The silencing of human rights activists like al-Hathloul is being endorsed by the Specialized Criminal Court, which was created in 2008 to prosecute thousands of detainees who were kept in detention “without charge” since terrorist attacks started occurring inside Saudi Arabia in 2003. However, a few years later the extremist terrorists would be replaced by women trying to make their voices be heard. Writers, economists, journalists, religious clerics, reformists, and political activists would also be detained in an attempt by the crown prince to establish his authority over anyone who campaigned against him.

“The Saudi Arabian government exploits the SCC to create a false aura of legality around its abuse of the counter-terror law to silence its critics. Every stage of the SCC’s judicial process is tainted with human rights abuses, from the denial of access to a lawyer to incommunicado detention, to convictions based solely on so-called ‘confessions’ extracted through torture,” said Heba Morayef, Amnesty International’s Middle East and North Africa Regional Director.

Loujain al-Hathloul was brave during her battle with the crown prince’s regime. She wasn’t afraid to “confess” to taking actions that promote women’s rights in Saudi Arabia, advocating for those unjustly detained before her, talking to journalists, diplomats, and representatives of international human rights organizations, and speaking publicly about the lack of freedom in her country.

The crown prince continues to market himself as a voice of progress. He is determined to make Saudi Arabia a regional power and, for that, he needs the support of powerful Western “friends.” These “friends” however advocate for democratic ideals. MbS must adapt to the image of the “Western leader” if he wants to be considered a reliable player and not an unstable oligarch. Also, the new generation of Saudis are starting to emulate the neoliberal trends the West has to offer. Saudi Arabia is not a typical isolated Middle Eastern country, due to its significant trade relations with the rest of the world. And it should act like a Western country by incorporating the shine of the “liberties are given as long as they serve the profit” model.

And that’s why the lifting of the driving ban happened in the first place. It is part of a plan to boost Saudi Arabia due to low oil prices. Saudi authorities are now trying to push more Saudis, including women, towards private sector employment because the state budget can’t support them. This is the political reason behind the “Vision 2030” MbS is promoting, which aims to have women’s participation in the workforce reach 30% by 2030.

The regime wants to give women “rights” only when it fits its agenda. It is just a distraction from the fact that women in the country will know true equality only when it is economically profitable. That’s why despite some progress women are not part of any legislative bodies. That’s why they are still prosecuted. And that’s why their struggle is far from over.