Longform

Maybe Cuba Should Have Kept Those Soviet Nukes

The Nuclear Security Summit in Washington reminds us that President Obama won his Nobel Peace Prize in large part because of his stated intentions concerning nuclear non-proliferation.

The two most recent achievements in US counterproliferation (Libya) and non-proliferation (Iran) have been tarnished by the destruction of Libya as a counter-proliferation example for North Korea by the deposition and murder of a WMD-bereft Muammar Qaddafi; the US inability to follow through on President Obama’s ambitions to bring Israel into the NPT fold as a self-acknowledged nuclear weapons power; and by US acquiescence to brutal Saudi Arabia-led rollback operations against Shia forces in Syria, Yemen, and Bahrain as compensation for US-Iran rapprochement.

In contrast to most sane Americans, I am not an enthusiast for the NPT-enforced oligopoly of a few nuclear states. I think it distorts foreign policy, particularly American foreign policy, which is keyed to the idea of leveraging the US “nuclear umbrella” to establish the United States as the indispensable security power everywhere and anywhere.

In Asia and the Middle East, beyond a continual need to validate its credentials as the biggest bully on the block, the US is trapped into reacting and overreacting to inhibit adversaries and allies alike from doing the obvious: acquiring a nice, neat, powerful, and not-too-expensive nuclear deterrent as an alternative to US dominance of their security regimes.

The United States commentariat is publicly appalled at Trump’s casual comments about South Korea and Japan going nuclear. Me, not so much. I think everybody would behave better if their neighbors had nukes. And the United States would not have so big an incentive to militarize and escalate local frictions to create a plausible role for Uncle Sam and his magic nuclear umbrella.

In other words, in a world in which the US continually maintains and improves its nuclear arsenal while inhibiting the emergence of counterbalancing deterrence—and at the same time refusing to renounce nuclear first strike—maybe the big nuclear danger is trying to keep the nukes out instead of letting the nukes in.

Recall the immortal Casey Stengel debunking the canard that sex before a game was bad for ballplayers: “Being with a woman all night never hurt no professional baseball player. It’s staying up all night looking for a woman that does him in.”

So, what’s more destabilizing? Proliferation, or US-led anti-proliferation? Discuss!

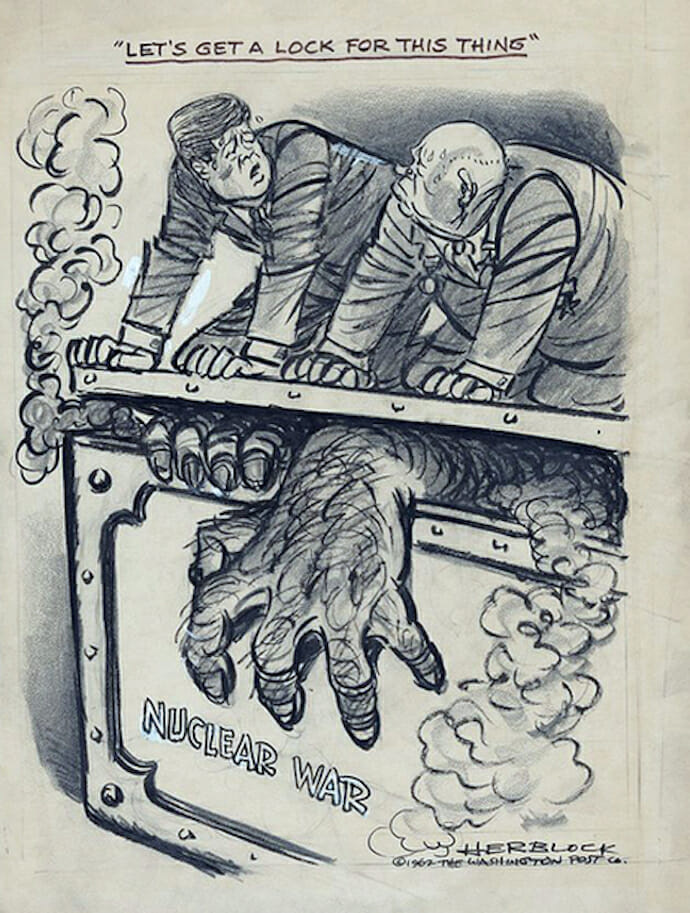

The one nuclear proliferation crisis everybody likes to cite to illustrate the benefits of anti-proliferation is Cuba 1962, when America’s Best and Brightest under Jack Kennedy stared down Nikita Khrushchev and his attempt to position strategic nuclear weapons in Cuba.

Let’s look at it another way: as the time the Soviet Union tried to beat (or at least match) the US at its own global nuclear hegemon strategy and failed miserably (fundamental contradictions need a good deal of experience, skill, strength, and luck to keep papered over, none of which Khrushchev had); a cautionary tale that allies and proxies don’t rate quite the same nuclear umbrella as the hegemon’s homeland (Japan and South Korea take note); and anitproliferation is expensive, difficult, dangerous, and involves plenty of knock-on consequences (North Korea, of course).

Revisionist history a.k.a. facts have as usual removed some of the good v. evil gloss slathered on the US by Kennedy hagiographers to reveal the political calculations underlying the confrontation.

It has emerged that Khrushchev was waaaaaaaay on the wrong end of the notorious missile gap, contrary to Kennedy’s claims during the 1960 election, with major shortfalls in operational ICBMs and no strategic submarine capabilities and, indeed, with only 300 strategic nuclear devices overall compared to 1500 for the US. Soviet strategists were appalled by the introduction of US Jupiter nuclear-tipped missiles into Turkey and Italy and justifiably anxious about the prospect of a pre-emptive US strike.

Kennedy understood that standing up to the Soviets over Cuba–antiproliferating–was more a matter of US (and his) credibility and a reflection of US determination over Berlin than an issue of US national security. From the beginning of the crisis, his advisors are unambiguous in their analysis that the missiles in Cuba, when operational, would not effect the strategic balance.

Missiles in Cuba were intended by Khrushchev as a stabilizing strategic riposte to the US missiles in Italy and Turkey and a neat way to succor Cuba and bind it into a Soviet alliance by deterring a widely expected US “regime change” style invasion.

Recently, the tape recordings of the Oval Office discussions during the crisis were declassified and, according to Benjamin Schwartz in The Atlantic, yielded this priceless nugget: “On the first day of the crisis, October 16, when pondering Khrushchev’s motives for sending the missiles to Cuba, Kennedy made what must be one of the most staggeringly absentminded (or sarcastic) observations in the annals of American national-security policy: ‘Why does he put these in there, though?…It’s just as if we suddenly began to put a major number of MRBMs [medium-range ballistic missiles] in Turkey. Now that’d be goddamned dangerous, I would think.’ McGeorge Bundy, the national security adviser, immediately pointed out: ‘Well we did it, Mr. President.'”

As for regime change, Soviet expectations were spot on; after the Bay of Pigs debacle the Pentagon was busy with Operation Mongoose planning for Castro’s overthrow. Declassified documents reveal that the US would, as usual, take the high ground by invading only in response to a Cuban outrage, albeit one manufactured by the CIA.

One scenario, thanks to an anonymous writer with a strong historical understanding of what had worked in US-Cuban relations: “Remember the Maine incident could be arranged in several forms. We could blow up a U.S. ship in Guantanamo Bay and blame Cuba.”

The most interesting element of denuclearizing Cuba is that the United States didn’t think that the Soviet Union had any operational nuclear weapons capability in Cuba when it decided to go public and issue the ultimatum to Khrushchev.

In a piece I wrote about dead horses in Soviet Ukraine (one of my favorite pieces about a pivotal event in Ukrainian history—must read!) I remarked in passing on the assertion by Victor Marchetti, a CIA whistleblower perhaps little remembered today, but a big deal in the last century: “Marchetti, by the way, claims to have been intimately involved in the intelligence aspects of the Cuban crisis. He alleges that President Kennedy was well aware that the missiles in Cuba were still lacking their warheads and therefore posed no threat to the United States. Nevertheless, Kennedy and his hagiographers, perhaps in order to provide America’s youth with sufficient pretext for a frantic pre-apocalypse fuckfest, have skated over this aspect of the crisis.”

According to Marchetti: “[We didn’t] come as close to war as many think, because Khruschev knew he was caught. His missiles weren’t armed, and he hadn’t the troops to protect them. Kennedy knew this, so he was able to say: ‘take them out.’ And Khruschev had to say yes.”

Ah, history. Or, as we say, “Whaddya know?”

Well, at the time Marchetti wrote that in 2001, the USSR had met its demise, rehashing the Cuban Missile Crisis had become a cottage industry and occasion for mutual backpatting by Russian and US national security types who had saved the world, at least certain paleskinned bits of the Northern Hemisphere, from destruction…

…and it was pretty categorically stated that Cuba was loaded to the gunwales with nuclear weapons in October 1962, when the crisis started…

…and Marchetti was defending his initial, less alarmist assessments and dismissing the subsequent revelations as nefarious tag-team U.S.-Russian Federation disinfo…

…so post-1989 revelations do have to be parsed carefully since the Cuban missile crisis is apparently still a useful text for geopolitical jockeying between Russia and the United States…

…but emerging documents and memoirs pretty convincingly support the latter assessments.

Anyway.

162 gadgets is the number bandied about, a mixture of strategic warheads for the medium and intermediate range missiles targeting the US, and 92 tactical nuclear devices, especially cruise and short range missiles but also including a pair of nuclear mines.

And as for Khrushchev “not having the troops,” there were allegedly forty thousand Soviet troops in Cuba, not the few thousand estimated by Marchetti and the CIA, infiltrated together with shiploads of military equipment under the noses of the CIA and including infantry, anti-aircraft, and other defensive units to protect the core strategic nuclear force.

Soviet forces were commanded by officers whose concept of operational routine was the Great Patriotic War against Nazi Germany, had control over those tactical nuclear weapons, and had authority to use them if the U.S. invaded and communications with Moscow were severed. Plenty of material, in other words, to turn Cuba into a major battlefield, starting with the U.S. base at Guantanamo as a focus of Soviet attentions.

Here’s a photo of the general in charge of Soviet forces in Cuba, Issa Pliyev, wearing the “volunteer” civilian garb he detested, standing with Castro, who is wearing the rarely-seen clunky glasses that, apparently, he detested)…

However, Marchetti is, in terms of American perceptions at the time, correct and, in terms of Soviet strategic capabilities, apparently operationally on point.

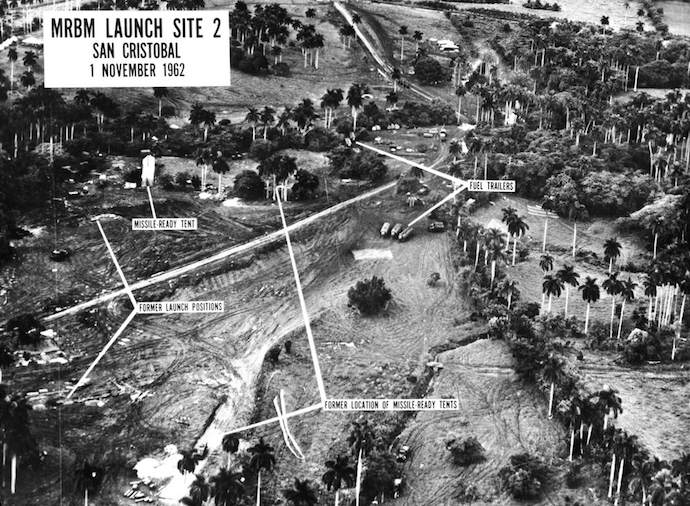

According to the record, even after a U2 flight yielded unambiguous photographic evidence that, indeed, the Soviets had established intermediate and medium-range missile launch facilities in Cuba (built under a crash program involving the labor of hundreds of thousands of Cubans), the CIA didn’t know for sure that the warheads had arrived in Cuba.

Indeed, the photos reveal something that looks more like construction sites than comfy bases of mass destruction (the Soviets apparently cloned their homeland missile facilities in Cuba, making photo analysis of the nature and progress of the projects a bit easier), supporting the inference that the warheads were not yet on site and integrated with the missiles. The CIA conclusion appears to have been that the warheads weren’t there and if they were, they were off in some warehouse somewhere and the missiles were unarmed. It turns out the CIA was if not completely right, it was not completely wrong; the warheads for the strategic missiles, it transpires, were in Cuba but had not been deployed to the launchers yet.

Another indication that the strategic missiles were not operational in October 1962 is that Khrushchev was not yet prepared to formally announce their existence.

Apparently, Khrushchev planned to announce the existence of the missiles during a visit to the United States in November 1962, bringing to mind this exchange from Kubrick’s 1964 film, Dr. Strangelove:

Dr. Strangelove: Of course, the whole point of a Doomsday Machine is lost, if you keep it a secret! Why didn’t you tell the world, EH?

—Ambassador de Sadesky: It was to be announced at the Party Congress on Monday. As you know, the Premier loves surprises.

As for the tactical nuclear weapons, McNamara states that his knees wobbled when he was told about them at a thirtieth anniversary get-together in 1992 between the US, Russia, and Cuba. However, this was apparently not the first he had heard of them.

According to the Kennedy tapes, by October 29, 1962 it was known thanks to low altitude surveillance that there were nuclear capable Soviet tactical missiles on Cuba, and US military commanders were asking for permission to use tactical nuclear weapons in the planned invasion: McNamara himself refused. I’m guessing McNamara chose to assume (erroneously) the missiles were not nuclear tipped and this was the version presented to Kennedy.

Therefore, President Kennedy had the certain luxury of gaming his Cuba scenarios on the assumption that the confrontation would play out within the context of a potential direct nuclear exchange between the US and Russian homelands, and that the risk of losing the aspirational but as-yet non-operational Soviet installations in Cuba would perhaps not justify nuclear Armageddon in Khrushchev’s eyes.

The consensus opinion in Washington in October 1962—buttressed by the reports cited by Marchetti that the warheads had probably not arrived and there weren’t a lot of Soviet troops on the island–was to launch massive airstrikes followed by invasion to take out the missiles (and also, though it’s not much discussed in the official hagiography, deal with that pesky Castro problem once and for all in a geostrategic twofer). However, according to McNamara, Kennedy was swayed to go for the quarantine + ultimatum with airstrikes + invasion to follow option instead by the general in charge of U.S. Tactical Air Command, who cautioned that maybe a nuclear-armed missile might survive the massive U.S. strike to hit the United States.

In other words, the group opinion was 99% sure everything would go great, but Kennedy wanted 100%.

If the group opinion had prevailed and the US had invaded Cuba and been surprised by 40,000 nuclear-armed Soviet troops, things would have gone south in a hurry (together with McNamara’s knees and career). Which is why expert opinion has started to tilt away from “masterful statesmanship” toward the “lucky accident” interpretation of the crisis.

As it transpired, the most immediate nuclear risk during the crisis didn’t even involve the weapons on Cuba. It was created by the US Navy enthusiastically depth charging a Soviet sub nearing Cuba that was armed with a nuclear torpedo. Unaware that the USN was dropping undercharged “we want you to surface and identify yourself” ashcans and not “we want to sink you” depth bombs and worried that his vessel was about to be destroyed, the Soviet captain decided to dish out his 10-kiloton nuclear torpedo and go down in a blaze of glory. Fortunately, the launch was vetoed by his flotilla commander, who happened to be on the boat. The sub, happily, survived, as did significant swaths of the Soviet Union and US.

Khrushchev eventually obliged Kennedy, climbing down in a nice superpower-to-superpower way, receiving in return a pledge that the United States would not invade Cuba (a pledge honored somewhat in the breach) and a sub voce US undertaking to remove soon-to-be-obsolete Jupiter missiles from Turkey and maybe Italy (which were subsequently replaced by invulnerable sub-based Polaris missiles).

And that, of course, did not oblige Fidel Castro, who regards Khrushchev as an ass and a wimp.

An ass, because instead of declaring to Kennedy that the missiles were a deterrent and an sovereign Soviet security interest covered by the USSR’s nuclear force when a U2 flight detected initial signs of missile facility construction in August 1962, Khrushchev fudged and called them defensive (with the apparent mental reservation that “defensive” meant “offensive weapons that defend Cuba by virtue of their deterrent function”). This put the Soviet foreign policy establishment on the wrong foot in vigorously and credibly defending the initiative when it turned out in October that there were four dozen strategic missiles in the package capable of reaching most of the continental United States.

And wimp, because Khrushchev backed down in October 1962 and threw Cuba under the bus. Cuba under Castro had irrevocably burned its bridges to the United States by hosting the missiles, and was ready to do that socialist shoulder-to-shoulder thing and risk US annihilation in an attack if the USSR was ready to take out the United States in retaliation.

Khrushchev caved to the US and removed all the nukes, not just the strategic weapons he had promised Kennedy to remove, but also the tactical nuclear weapons he had promised Castro in the initial agreement would eventually be delivered to Cuban control—and Washington didn’t even know about.

So instead of getting a powerful, nuke-based alliance with the USSR that would give Castro bargaining leverage against US security and economic coercion—and maybe diplomatic recognition, who knows? The US had extended the courtesy to a number of Soviet proxies with considerably less national legitimacy than Cuba– Cuba was left as a lonely piñata twisting in the wind while the US took whacks at it for over 50 years. President Obama marked the continuation, rather than conclusion, of the effort by going to Cuba for a triumphal visit that was interpreted, especially in the United States, as receiving the Castros’ surrender to the forces of US democracy and capitalism, notwithstanding Raul Castro’s effort to literally spin Obama’s flaccid wrist into a display of transnational popular solidarity.

Here’s how those socialist photops are supposed to look, by the way.

For the Soviet Union, a dismal botch that helped cost Khrushchev his job and, coming on the heels of the China debacle, pretty much put paid to Soviet overseas nuclear junketeering.

While the Soviet Union was out of the proliferation game, the US went all in on nukes as a geostrategic asset, not only maintaining its nuclear edge through technological improvements and integrating nuclear weapons into its security architecture in Asia as well as Europe, but also by antiproliferating, by seeking to deny new aspirants, allies as well as adversaries, entry to the club through suasion, sanctions, and even war.

In an interesting way, the US is now somewhat recapitulating the Soviet endgame in Cuba, with elements in Japan and the Republic of Korea becoming more vocal about their desire to control their own nuclear destinies rather than rely on the United States, thereby challenging the US nuclear weapons monopoly and the Asian security architecture which it underpins.

The forces advocating for nuclear proliferation are many; the US, while not standing alone as an anti-proliferater, is perhaps alone in its depth of conviction, interest, and determination. This creates challenges for President Obama as he tries to universalize the internationalized NPT legal regime and wean the United States from unilateral anti-proliferation and its occasional resort to violations of sovereignty to achieve its objectives.**

What about Cuba? What would have happened if the USSR, instead of putting its own nukes on Cuba, had just given Cuba some nukes? Or, in a strikingly plausible scenario, let Castro keep the tactical nukes after the Soviets withdrew? How would US relations with Cuba and the rest of Latin America evolved?

Looking at the cavalcade of instability in places like Chile, Argentina, Colombia, Honduras, and Guatemala engendered by the successful US rollback of socialism after Khrushchev bugged out, Latin America would certainly have been different if Cuba had nukes…and maybe not worse off.

But that’s a possibility the US, for obvious reasons, has no interest in exploring.