Media

Melania Trump, The Daily Mail and a History of Libel Tourism

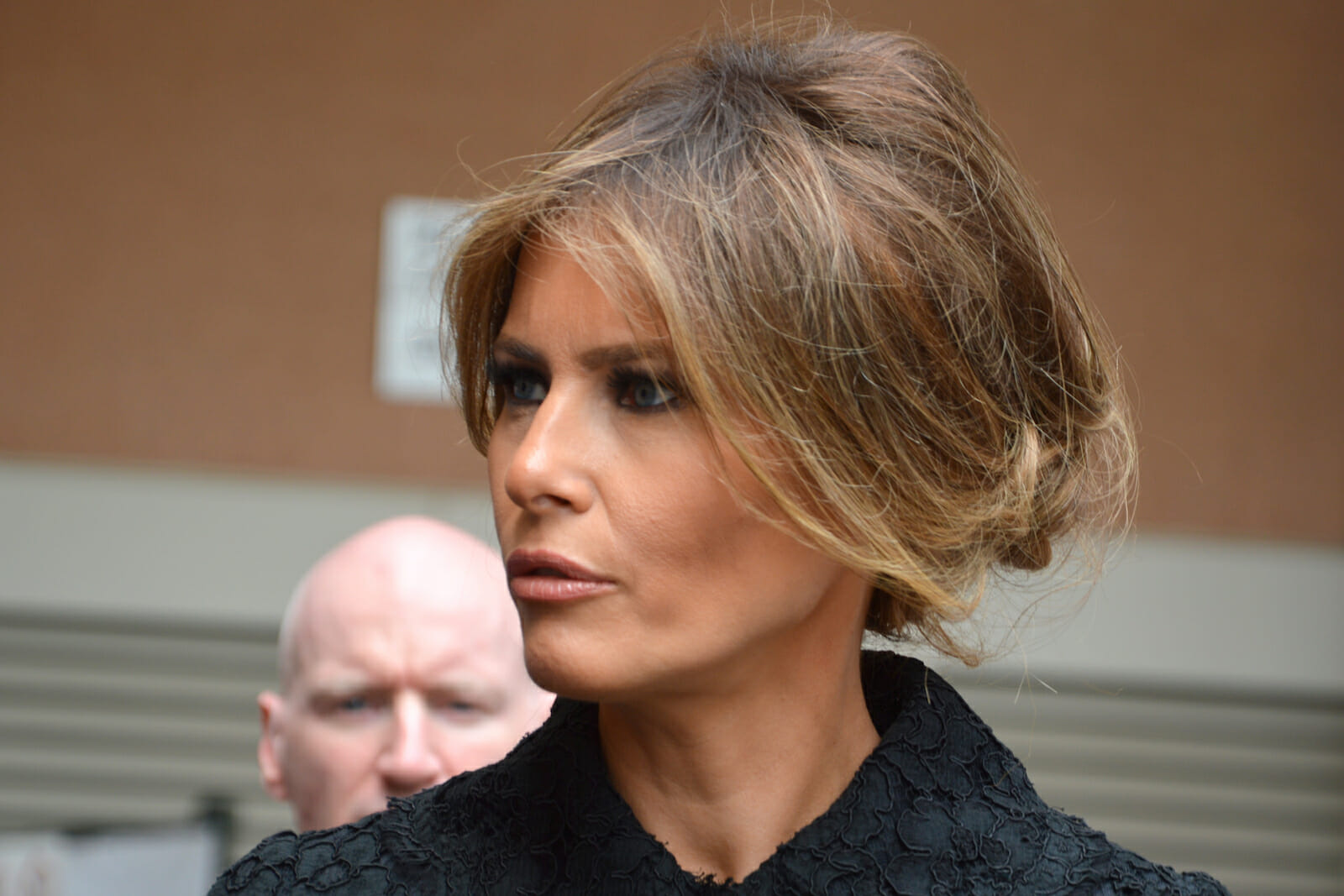

Readers of the Daily Mail were recently treated to a fairly rare event: the paper published a retraction of a news story it had run about Melania Trump, the wife of the Republican presidential candidate and prospective first lady of the United States. The retraction related to a story published both in the newspaper and the Mail’s website, which repeated allegations from an unofficial biography of the third Mrs Trump.

These allegations – which are recited in the complaint and have been widely repeated on the internet – relate to her immigration status, the circumstances in which she met her husband and her employment when she first came to the United States. Given her husband’s position on illegal immigration, the first of these might have proven to be the most politically sensitive allegation.

The retraction followed the filing of a complaint, in a Maryland court, against the Daily Mail and another defendant – a blogger who made similar allegations. It appears that the complaint is only in respect of the article’s publication on the Daily Mail’s website, rather than in the print version. However, the retraction appeared online and in the paper.

Libel tourism

Such a claim, by a US citizen against a British publication, raises issues of jurisdiction and it is interesting that the complaint was filed in the US, rather than in the more claimant-friendly jurisdiction of England and Wales. While the Daily Mail is a British newspaper, its website has a significant international readership: the court papers refer to United States web traffic of 2m visitors per day.

But the Daily Mail’s article was most prominently published in England and Wales and it might have been reasonable for Trump to issue proceedings in the High Court. However, recent changes to both English and US law have significantly restricted the ability of claimants to start legal claims outside their own country of residence.

Until fairly recently, English courts were relatively relaxed about “forum shopping” or “libel tourism” in defamation. In cases where the publication took place outside the claimant’s own jurisdiction, English courts were easy to persuade that they should hear the claim. When Liberace was defamed by the Daily Mirror in 1956, he chose to sue in England and Wales – he was entitled to protect his considerable reputation in England. If the Daily Mirror had been available in the United States, then he might have chosen to sue in that country. To a large extent, the decision was up to the claimant.

However, there has never been an unrestricted right for non-residents of England and Wales to bring claims in English courts. In 1937, M. Kroch, a resident of France, who had been defamed in a Belgian newspaper, was refused permission to bring a claim by the Court of Appeal. The report does not explain why M. Kroch wished to sue in England, but it does record that he failed to establish any sort of reputation or connection within the jurisdiction, apart from staying in rented rooms while bringing his claim.

However, as long as the claimant had a reputation within the UK, and the libel had been published – in defamation terms, that the words had been read by a person other than the author or subject of the statement – the courts would grant permission for the case to proceed.

It is fair to say that the bar was very low, both in terms of the claimant’s public profile within England and Wales and the extent to which the statement was published. In the 2005 case of Khalid Salim Bin Mahfouz and others vs Dr Rachel Ehrenfeld, the Saudi businessman sued Ehrenfeld, an American author, for alleging that he had helped to fund terrorism. While the claimant had some connection with England and Wales, Ehrenfeld had none – and the book in question was not published in the UK. However, the first chapter was available online and 23 copies had been sold, via the internet, to buyers in England. This was a sufficient connection with England and Wales for the High Court to allow the claim to proceed. The court found for the plaintiff.

Protecting free speech

The Ehrenfeld case, and other high-profile claims, provoked a strong reaction in the United States – the state of New York enacted the Libel Terrorism Protection Act in 2008 and, in 2010, Congress followed suit with the Securing the Protection of our Enduring and Established Cultural Heritage (SPEECH) Act.

Both these acts prevent American courts from enforcing English (and other jurisdictions’) libel judgments, unless the foreign court provides at least the same level of protection to free speech as American courts. It should be noted that, by treaty or as a matter of international comity, courts will generally enforce international judgments.

On the British side of the pond, the Defamation Act 2013 also tackled the issue of libel tourism – now, where the publisher is not a resident of the UK or other Lugano Convention countries, the court has to be satisfied that England and Wales is “clearly the most appropriate place in which to bring an action.” However, this would not necessarily prevent a non-resident, such as Mrs Trump, from bringing a claim in respect of a publication within England and Wales.

Given the context of the current presidential election campaign and the importance of Melania Trump’s reputation as reflecting on her husband, it is how this will play out with American voters that is important – so it is the coverage in America and the chance to answer those allegations to the American public that matters most. Given this, it would have been difficult to argue that England was the most appropriate place to take action.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.