Moldova: Is Neutrality Still an Option?

In late May, the government of Moldova expelled five Russian diplomats, accusing them of espionage and for, according to a Reuters report, “recruiting fighters for the Moscow-backed insurgency in neighboring Ukraine.” Since achieving independence in 1991 and following the 1992 war that created the separatist region of Transnistria, Chisinau has had a difficult time remaining neutral in the geopolitical game between the Russian Federation and the West. Given regional challenges, like the conflict in Ukraine and NATO expansion (Montenegro became its 29th member on 5 June), it is improbable that Chisinau can remain neutral for long.

A Confusing Home Front

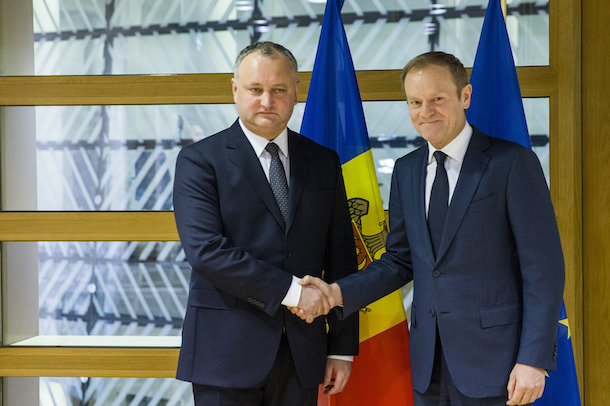

Trying to understand Moldovan foreign policy today cannot be done without discussing the country’s troubling internal politics. Current President Igor Dodon is well known for his pro-Moscow attitude. In fact, he visited Moscow in March, where he denounced his government’s current pro-Europe stance, since “as a result, we have actually lost our traditional Russian markets and failed to obtain new ones.” Additionally, the breakaway region of Transnistria continues to have a Russian military presence (Russian troops carried out exercises in June), which Moscow labels as peacekeepers even though Chisinau has repeatedly demanded that they should withdraw. Finally, it is important to note that in the south of the country there is a small region known as Gagauzia. In 2014 the region held a referendum, which Chisinau labeled as unconstitutional, in which it rejected a proposed plan for Moldova to sign a trade agreement with the European Union (EU) and rather supported closer ties with the CIS Customs Union, a Russia-backed alliance.

On the other hand, recent prime ministers (the real policymakers, as presidents have a largely symbolic role) have generally maintained a pro-Europe/West stance, including current PM Pavel Filip. This situation is best exemplified by the 2014 EU-Moldova Association Agreement.

Complicating the situation are Moldova’s seemingly never-ending political crises which have resulted in a string of elections and a revolving door of coalition governments. The 2009 crisis in which President Vladimir Voronin resigned is an example of this situation. In 2015, protests erupted when it was revealed that an astounding $1.1 billion had disappeared from the three leading Moldovan banks.

Most recently, in late May members of the Liberal Party, Education Minister Corina Fusu, Deputy Education Ministers Cristina Boaghe and Elena Cernei, Environment Minister Valeriu Munteanu and deputy ministers Igor Talmazan and Victor Morgoci, offered their resignations, to protest the detention of Chisinau city mayor, Dorin Chirtoaca, and Transport and Roads Infrastructure Minister Iurie Chirinciuc by the National Anticorruption Centre.

Moldova’s unstable domestic politics will inevitably influence its foreign policy, as the country is approaching Europe but also has to address a separatist, pro-Moscow Transnistria and a potential problem in Gagauzia. According to reports, the Moldovan citizens who have travelled to Russia and from there to Ukraine on behalf of the rebels were from Gagauzia. In such a complex situation, formulating a long-term foreign policy is quite the challenge.

Moldova in Europe’s Great Game

In 2009, the author of this commentary published an essay in the Journal of Slavic Military Studies entitled “The ‘Frozen’ Southeast: How the Moldova-Transnistria Question has Become a European Geo-Security Issue.” Said article discussed how NATO’s and the EU’s eastwards expansion, which included accepting Romania as a member in 2004 and 2007 respectively, meant that Moldova and its internal problems were directed at the EU and NATO’s borders.

Fast forward almost a decade since that piece and now it is external events that are having an impact in Moldovan affairs, like the war in Ukraine, which resulted in the Gagauzian affair. Additionally, in May there were reports that Kiev was considering closing its border with Moldova as the separatist Transnistria borders Ukraine – what actually happened was that Kiev and Chisinau opened a border checkpoint in Transnistrian “territory,” a move that separatist authorities condemned. Even more, when Crimea was annexed by the Russian Federation in 2014, Transnistrian leaders requested that Moscow annex their region too. Moscow declined at the time.

At this point, it is important to keep in mind Article 11 of Moldova’s constitution, which states: “The Republic of Moldova proclaims its permanent neutrality,” and “The Republic of Moldova shall not allow the dispersal of foreign military troops on its territory.” Hence, the country cannot join military alliances like NATO. Nevertheless, pro-Western governments in Chisinau have tried to work around that issue by carrying out other defense initiatives. For example, Moldovan troops have participated in the Kosovo Force in 2014 and there are current plans to open a NATO civilian-staffed liaison office in Chisinau, a move that President Dodon has protested against.

This is the core of Moldova’s foreign policy woes as it tries to find a place in the West-Russia Great Game. If the government tries to approach the West, this move will be denounced by pro-Russian Moldovan politicians, including the President himself. Additionally, there is the concern regarding how will Transnistria, and even Gagauzia, respond if Chisinau attempts to seek even closer commercial links with the EU or security ties with NATO?

The recent incident in Gagauzia and Chisinau’s decision to expel five Russian diplomats (to which Moscow retaliated by expelling five Moldovan diplomats), brought bilateral relations to a new low. Nevertheless, it is necessary to stress that the two nations maintain close ties; for example Russian-Moldovan commerce is important, exemplified by a Russian 2014 ban of Moldovan produce (a retaliatory measure for approaching the EU), which hurt the landlocked nation’s economy. Additionally, many Moldovans migrate to Russia to work and send remittances to their families at home – Radio Free Liberty/Free Europe explains that “there are an estimated 500,000 Moldovans working in Russia.” Should bilateral relations become even more strained, Moscow could stop accepting Moldovan migrant workers, which would hurt the country’s economy even more. Moldova is likewise dependent on Russia for energy. RFL/FE reported in mid-July “98 percent is imported, most of it from Russia, and the imports are transported through the breakaway Moldovan region of Transdniester” and how “Moldova’s electricity usage, 70 percent is generated in Transdniester.”

Nevertheless, President Dodon’s statement that Moldova is suffering because it has lost access to the Russian market is an exaggeration. According to a 27 June article by Moldova.org, “since 2014, the European Union has become the main trading partner of Moldova. More than 63% of Moldovan exports are now directed to the EU and half of imports come from the EU. And there’s a positive trend in this. In the period January-April 2017, Moldova exported goods worth 430 million euros to the EU, 16% more than in the same period of 2016.”

Additionally, in early July the European Parliament approved a 100-million euro aid package for the landlocked nation, consisting of a loan of 60 million euros and a grant of 40 million euros. Such amounts, if adequately utilized, could continue to help Chisinau revitalize its economy.

As it stands, Moldova appears to be increasingly turning towards Europe for trade relations, but the country does remain dependent on both Russia and Transnistria.

The 2018 Elections

Could Moldova switch its foreign policy and approach Russia? This is theoretically possible. After all, the 2016 election of President Dodon is regarded as a protest vote by the population after several pro-West governments not only failed to improve the country’s economy but also failed to crack down on pressing problems like corruption. Certainly parts of the population, including most Gaugazians, if the 2014 referendum is to be believed, would prefer stronger Chisinau-Moscow ties, however, the succession of pro-West governments, the election of President Dodon notwithstanding, hints that most Moldovans would prefer closer relations with the EU and, probably, NATO as well.

Moldova is scheduled to have parliamentary elections in 2018. Current rumors, including interviews carried out by the author with experts on Moldova, suggest that the pro-Moscow Socialist party could emerge victorious, not necessarily because the majority of the general population looks with kinder eyes to Russia than to Europe, but rather as a sort of protest vote for mismanagement when it comes to domestic politics and the economy – e.g. the disappearance of USD 1.1 billion, which would unnerve anyone. (Political preferences among the Moldova electorate due to age differences is not the main focus of this analysis, however, experts stressed the importance of this issue to the author as the elections approach).

As a final point, it is important to mention a recent scandal involving “a network of nationalists, radicals, and neofascists across Eastern Europe,” led by Belarusian Alyaksandr Usovsky, with ties to Russian State Duma Deputy Konstantin Zatulin. The emerging narrative is that this network was trying to influence upcoming elections in Europe, which included working on a project apparently called “Moldova Is Not Romania.” Similarly protests have erupted over a controversial electoral law that was passed in mid-July. It appears that both exterior agents as well as controversial decisions by domestic policymakers will influence the outcome of the 2018 elections in Moldova.

How Do You Formulate A Foreign Policy?

Attempting to suggest a foreign policy for a country like Moldova inevitably means addressing a plethora of issues that must be taken into account. This analysis has attempted to briefly describe the most important challenges, like the country’s pro-Moscow president against a pro-West prime minister and parliament, ongoing protests and scandals regarding corruption (including the missing USD$1.1 billion), also we must add breakaway Transnistria, a potential growing problem in Gagauzia as well as Moldova’s ongoing dependency on Russia for jobs and trade, and on Transnistria for energy.

Charting a foreign policy for, say, the next five years is no easy task – we will have to wait until the 2018 elections to see which political parties emerge victorious in order to have a better idea of how domestic politics will guide future foreign policy projects. With that said, the point here is that the country’s ongoing diplomatic stasis is not working. The 2014 trade agreement with the EU was a major diplomatic development, which prompted a Russian backlash. However, apart from that issue, and a potential NATO liaison office, there has been no major breakthrough or initiative out of Chisinau. Moreover, the Transnistria issue remains, for lack of a better term, ‘a frozen conflict.’

Nevertheless, even if Chisinau does not appear to have, in this author’s opinion, a diplomatic blueprint with clear objectives, the region around the country is changing and it will affect Moldovans one way or another. For example, the conflict in Ukraine will continue to have repercussions in Moldova, e.g. the Gagauzians or the 2014 Tranisnistrian request to join the Russian Federation or issues regarding the Moldovan-Ukrainian border. As a corollary to this article it is worth noting that an ongoing development was Romania’s decision to not allow a S7 commercial aircraft to cross Romanian airspace and land in Moldova because it was transporting Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin, who is under Western sanctions – the airplane had to land in Minsk, Belarus. Rumors abound about the incident, including whether Bucharest was “asked” to prevent Rogozin from landing in Chisinau so he could not meet with President Dodon.

There are certainly many Moldovans who would prefer their country to remain neutral when it comes to international affairs and alliances, but Moldova’s internal situation, its geographical location and the geopolitics in its neighborhood mean that neutrality is hardly an option anymore.

The author would like to thank Lucia Scripcari.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of any institutions with which the author is associated.