Tech

Automating Warfare: MonsterMind and Cloudy Diplomacy in Cyberspace

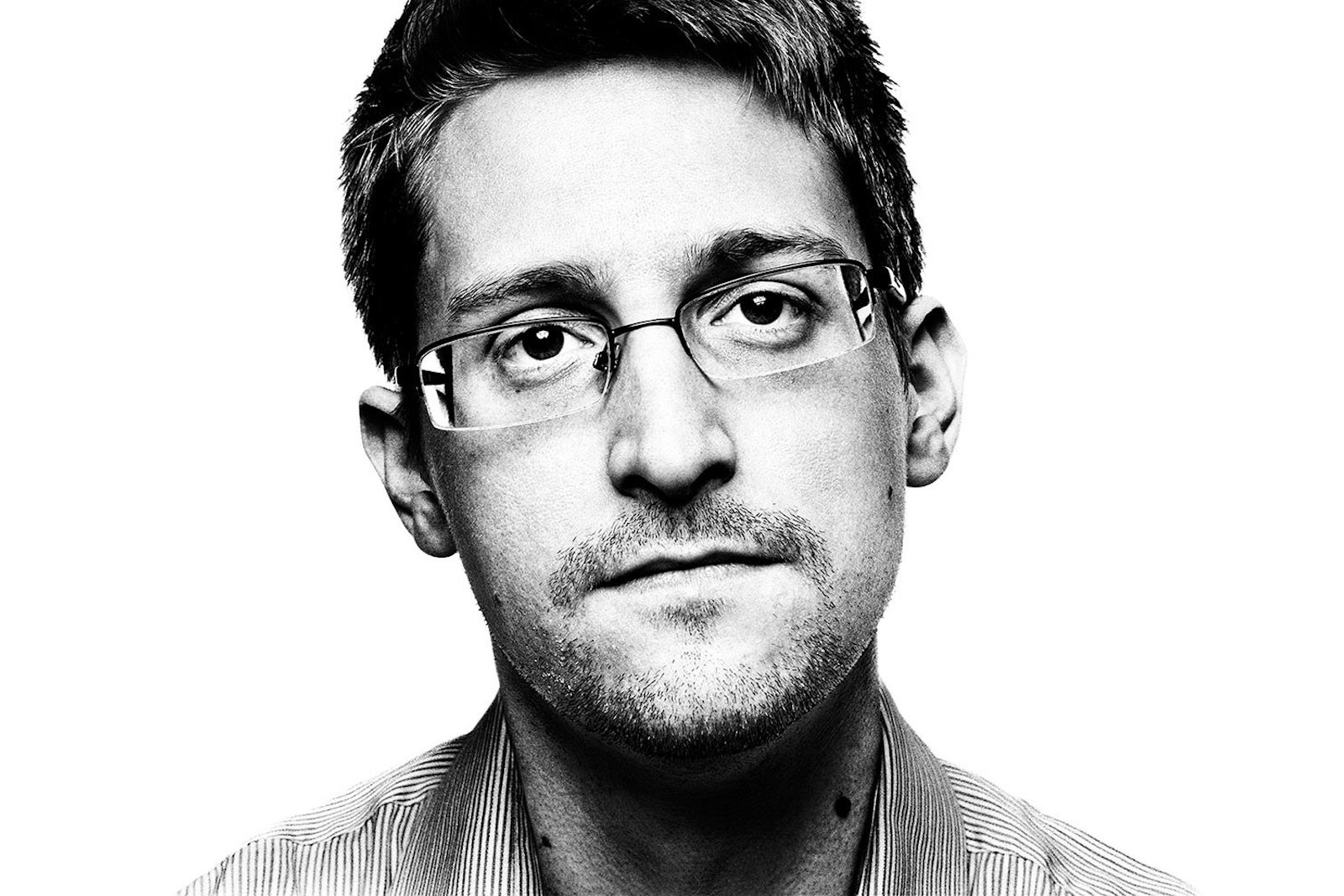

More than a year has passed since the revelation of the NSA’s surveillance programs surfaced to civilian levels, and in honor of the anniversary, Edward Snowden issued his newest installment of the National Security Agency’s technological advances in cyberspace. The program, known only as MonsterMind, has automated the process of hunting down cyber threats and then retaliating against those systems, all, according to Snowden, without much user participation.

Using a bot as sophisticated as MonsterMind is yet another example of the NSA’s desire to maintain the United States’ position as a leader in “all things warfare,” and this Snowden interview with Wired has yet to gain the same level of public traction and outcry as the PRISM program, which launched the whistleblower to stardom. The reason behind the limited backlash isn’t so much due to the fact that the general public doesn’t understand the implications of such a program. Instead it most likely stems from the fact that the NSA’s decision to build a program capable of defending America’s cyber infrastructure is the job of the agency.

The rise of cyber crime, espionage, terrorism, and warfare has become increasingly more prevalent in the information systems of every organization from US retail giant Target’s breach, which compromised the credit and debit card information of well over 100 million customers, to the more recent revelation of a group discreetly described in the media as a “Russian cyber gang,” which managed to accumulate the usernames and passwords of an estimated 1.2 Billion accounts from various websites.

As the frequency of research reports citing the Internet’s vulnerability has increased, the need for user-friendly systems and optimized efficiency in consumer technology and secrecy and complicity in classified technology has led to the growth of what may become the most diplomatically complicated terrain of warfare: cyberspace.

As the newest theatre of war, cyberspace has evolved from a military history that has a past that isn’t so well-known. Toward the tail end of the Yugoslav War, the Pentagon analyzed the possible use of cyber weapons against Serbia, to disrupt communication networks, yet nothing seemed to be put into use. Flash forward more than a decade later and attacks like the US-Israel joint worm Stuxnet have managed to infiltrate the most sensitive of government agencies, and successfully allow nations to carry out attacks with anonymity and ease, curbing international condemnation and removing the need to use more controversial weapons, like drones.

While physical weapons like guns, missiles, and tanks tend to dominate imagery surrounding war in the media, cyber-weapons can prove to be just as deadly. Services like public utilities in water, transit, and energy have prompted cybersecurity experts to call for swift action protecting services such as these from intrusion and manipulation. Enterprises like Saudi Aramco have seen their fair share of attacks and modern cyber weapons have proved to be capable of damaging critical infrastructure in the manufacturing and production activities of companies, through direct attacks on PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers).

More modern conflicts like the Israel-Hamas war has prompted Iran to enact revenge five-years later on Israel, by attempting, and eventually failing, to take down IDF-controlled public safety websites. Just over three months ago, the infamous Chinese-US bout concerning cyber espionage briefly brought back the spotlight on how governments need to evaluate their ability to anticipate and thwart the efforts of hackers, regardless if their motive is financial or political.

While the weapons pose their utility, they also encourage nations to develop more sophisticated cyber systems capable of both offensive and defensive. This type of build-up differentiates itself from other defense programs as having the distinction of being easily created by willing governments. There is no uranium to import and enrich, and intelligence agencies and media will have a much more difficult time figuring out about these weapons in their development stages. Even malware considered to be on-par of the damage of Stuxnet have its open source code publicly available, and is speculated to have been developed by a team of anywhere from 5-10 individuals and six months’ worth of work.

The ambiguity of what can and cannot be deemed as “cyber-warfare” has led to little cooperation from global organizations and associations in conducting diplomatic activities to combat the lack of specific legalese found in current warfare-specific international laws. While there has been discussion in forming a non-proliferation treaty to govern cyber weapons in academia, government activity to construct any to apply internationally has unfortunately faltered.

General civilian applications also posit questions regarding our level of security literacy and the possible damage that could arise from growth in information sharing. The alarming trend of societies’ dependency on transmitting sensitive data containing details on private matters like financial and healthcare data through cloud-based systems has become a double-edged sword of sorts, as it pits user simplicity against technical vulnerability. Building systems capable of maintaining a balance between the two variables is developing, but the continuous game of cat-and-mouse between security and hackers has become costly and could fiscally force many governments to compromise their security.

It would appear that the trigger needed to coerce governments into developing meaningful progress toward clarifying current international regulations and standards to apply to cyberspace would be a full-scale cyber-war itself, one with severe and devastating consequences.