‘One Child Nation’ Review

China’s one-child policy (OCP) ran from 1979-2015. This mandatory government program, as the name suggests, restricted women to only birthing one child. One Child Nation (co-directed by Nanfu Wang and Jialing Zhang) covers this controversial policy through both Nanfu Wang’s family history, as well as interviews with people who implemented and were affected by it.

Nanfu Wang met with the midwife who delivered her. She estimates that she conducted 50-60 thousand sterilizations and abortions, many of whom came from women who had been kidnapped by the government. Eventually, she quit due to overwhelming guilt; now, she runs an infertility clinic as atonement. By contrast, another female doctor named Jiang stands by the OCP and her role in it (which included aborting 8-9 month fetuses). Jiang argued that it was necessary to prevent China from collapsing from overpopulation. The OCP is estimated to have lowered China’s population by 400 million.

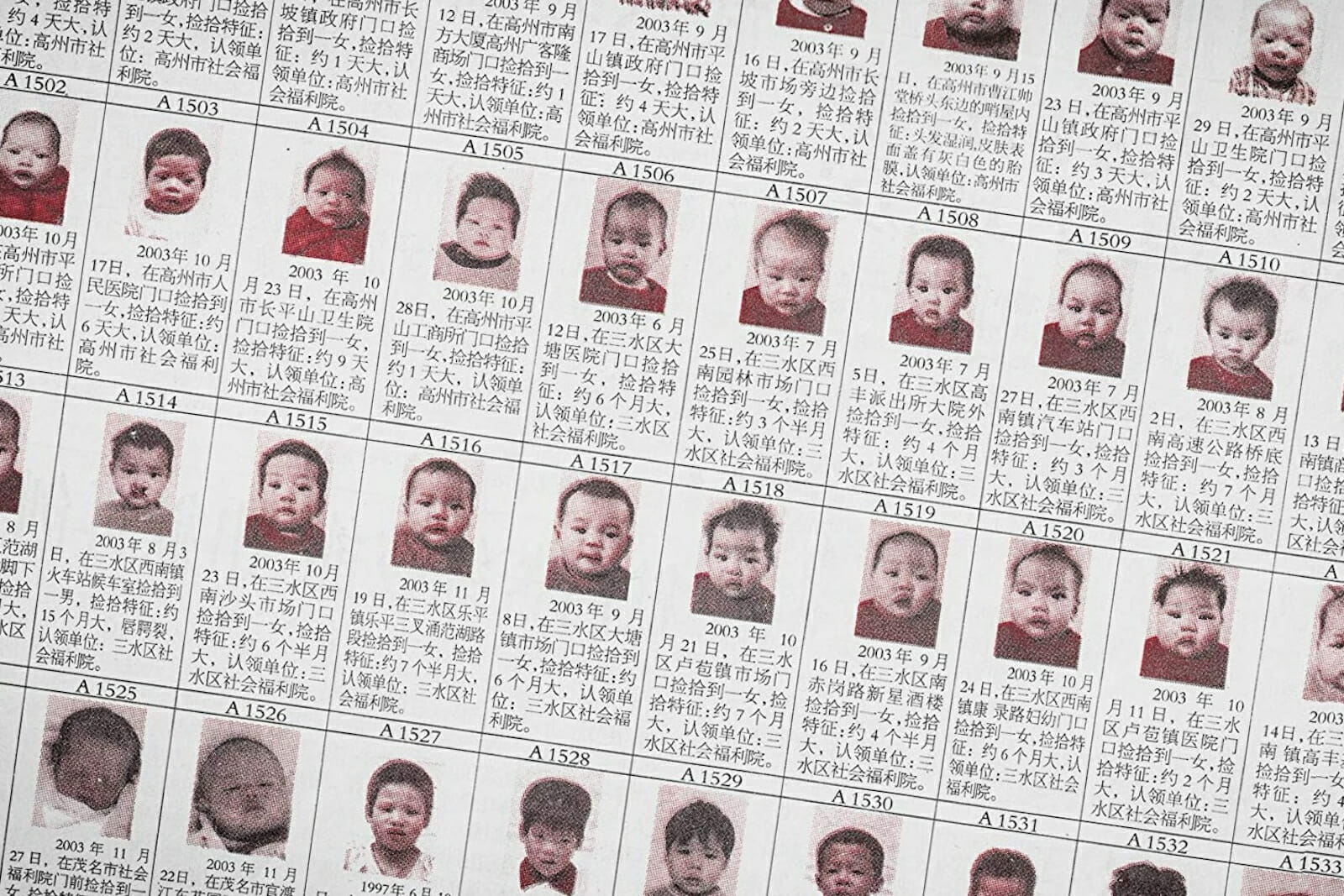

Not even the Chinese police state could abort every 2nd child in-utero. Thus, there were many illegal babies born (which unfairly also included twins). Nanfu Wang’s aunt and uncle described regularly seeing dead, abandoned babies lying around the market. Artist Peng Wang photographed many “dumpster babies.” These victims were overwhelmingly female, due to the patriarchal nature of Chinese society. The film disappointingly ignores the widespread persecution of newborns with disabilities; infanticide of babies with disabilities was so widespread, it lowered China’s ratio of people with disabilities by 2/5.

Nanfu exposes a dark conspiracy involving the 130,000+ Chinese babies who were adopted internationally. Yueneng Duan and members of his family admitted to selling 10 thousand abandoned babies to orphanages for $200 each, who would then adopt the children to international families. The Communist government made a big show out of the Duan family trial, but the family argued that they rescued the babies for free at first, due to pity, and that the children would have otherwise simply died lying where they had been abandoned. In other words, the Duan family feels that they were scapegoated for the Chinese government’s failure to handle the abandoned-baby crisis that they created.

Journalist Jiaoming Pang wrote an exposé (for which he was forced into exile) that uncovered that far more adopted children were never orphans left to die. Rather, they had been kidnapped from their families by corrupt local government agents. This “social maintenance fee” was an extortion racket that would kidnap babies, hold them ransom and then sell them to adoption agencies if the parents couldn’t afford to pay up. Government agents would sign off on a baby’s orphanage guardianship for as little as 50 yuan.

One Child Nation is a disturbing indictment of perhaps the most intrusive government policy ever enacted in history. Countless interview subjects rationalized their participation in the OCP, which they admitted was reprehensible, by resigning themselves to the fact that they “had no choice.” This is a common sentiment in totalitarian societies. The same top-down approach to governance that has lifted China out of poverty at a historic pace of just a few decades (due in part to the OCP) can likewise lead to great personal suffering. Great nations are always forged in Machiavellian psychopathy, such as the colonialism and slavery that built up America and Western European empires. It should thus come as no surprise that the Malthusian actions that helped China to eliminate hunger and limit urban overcrowding came at a huge cost for many innocent people. When analyzing history, it’s a difficult but necessary task to balance human rights as well as economic implications.