One Day in April of 1971

I met with a friend, an expat from Bangladesh like me, at a bar in Arlington on the eve of Bangladesh’s Victory Day on December 16 for drinks. It was already December 16 in Bangladesh because of the 11-hour time difference. After a few beers, my friend, who is 10 years older than me, offered to tell me a story. It was April 1, 1971. I was six years old. The West Pakistan Army unleashed its attack on East Pakistan on the night of March 25. We stayed in Dhaka for a couple of days until my father told us to get ready to leave the city on March 28.

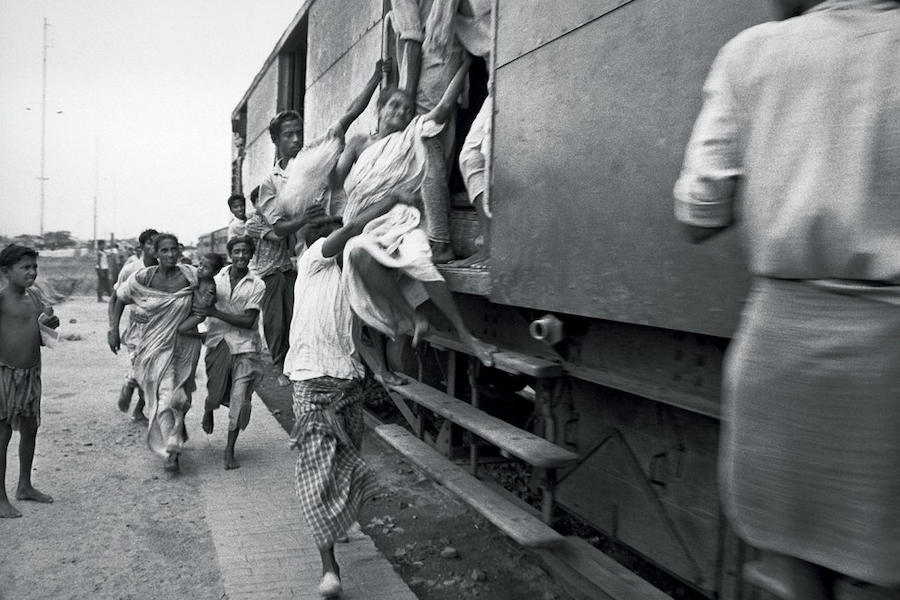

I fled Dhaka with my father, mother, sister, and grandmother to Jinjira, a city adjacent to Dhaka on the other side of the river Buriganga, just like many of ours neighbors did. All five of us piled up on a rickshaw, fit for only two passengers, and rushed to the bank of the river Buriganga and joined masses of people fleeing Dhaka.

We arrived at a relative’s house in the afternoon of March 28. The next few days were relatively calm. But that changed on April 1. The dawn was just breaking on that April fool’s day. But I was not fooled. The sound of gun shots and screaming of people told me that the “army” – a reference to the West Pakistan Army – is here. I remembered how the gun shots sounded on the night of March 25.

My father hurriedly woke us up – I was already awake — and put us in two groups, my mother, grandmother, and sister in one group and my father and I in the other group. My father held my arm. My mother held my sister’s and grandmother’s in each of her arms. My father told my mother to stay close. Then he said “bismillah” and led all of us to start “running” with the crowd. All I remembered about the crowd was that everyone was running in one direction. We started to run in the same direction.

I didn’t remember or understand all that was happening around me – people were talking, screaming, and crying. But I did not forget the non-stop running and walking. I remember my mother’s urging so many times to stop. She had to sit down on the side of the road with my grandmother and sister. One time, someone said, “A-re, pagol naki? Dou-ran, dou-ran.” Are you crazy? Keep running.

We stopped when we arrived at a house where men and women had to be in different rooms. So my father and I were separated from my mother, sister, and grandmother. My father and I did not know where they were. I kept asking my father where my mother was. He said she was safe. But I kept asking and then I started to cry and told my father, “The army is going to kill my mother.” My father held me close and said, “chup, chup.” Quiet. Quiet.

Everyone was anticipating the arrival of the army at the house. It was just a matter of time. The room we were in was directly behind the front door of the house. Time passed. Suddenly, the front door flew open. I distinctly remember seeing, but don’t know how, a cloud of dust and a black boot when the door opened. My father dove to the floor, holding me close to his chest, and crawled under a choki, a bed.

At the same moment, I heard the chanting of “Pakistan, jindabad. Pakistan, jindabad.” The chanting went on for a while. I thought I heard the voices of the army in Urdu. The chanting grew louder and bigger. And for some reason, I thought my mother, sister, and grandmother were dead and I wanted to cry. But I could not. My father pressed his hand tightly over my mouth.

My father loosened his grip when the chanting had stopped. He told me that the army was gone. But I wanted to know desperately where my mother was. And I knew she was dead. I started to cry. My father later explained to me that the chanting was a clever way of diffusing the Army. Those chanting saved our lives. The army was convinced that everyone was “in favor” of Pakistan in that house. So they left without harming anyone. After the army left, my father went to the room where the women stayed and started calling my mother’s name, “Minu, Minu.” I was crying and calling for her, “Amma, Amma.” Mother, mother. My mother was not there.

My father asked, no one in particular, whether anyone had seen a woman, a girl, and an older woman. Someone said to check the mosque adjacent to the house. My father and I went to the mosque and found my mother, sister, and grandmother huddled in one corner. I hugged my mother tightly. Then I kissed my sister on her forehead, and stooped down to touch my grandmother’s feet, a Muslim tradition of showing respect for the elderly. My father asked my mother whether we should stay in the mosque or go back to our house. My mother immediately said, “Na, na, cholen, cholen.” No, no let’s go. Somehow, my mother had the right instinct. And it saved us again. Later, we learned that the army came back and killed many people in that house.

That was the end of his story – about one day of the nine-month war in 1971 that gave birth to Bangladesh.